Three New Positive PFO Closure Studies May Turn the Tide in Cryptogenic Stroke

Experts are still concerned over how best to choose patients who will benefit but agree that percutaneous closure may have a role in select cases.

At long last, debate over the value of patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure versus medical therapy for the secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke may finally be winding down, following the publication of three new papers. Experts agree, however, that patient selection remains imperfect and further study will still be required.

Percutaneous PFO closure has been studied for more than two decades, marked by a series of negative, underpowered, and inconclusive trials. In 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the Amplatzer PFO Occluder (St. Jude Medical) for recurrent stroke prevention, making it the first device to be granted this indication, but limited its use to patients in whom percutaneous closure had been agreed upon by a cardiologist and a neurologist, having fully ruled out other causes of stroke. Historically, support for PFO closure has been stronger among cardiologists—especially interventional cardiologists—than among neurologists.

Last week, however, the New England Journal of Medicine published three new papers that may help to convince skeptics. These include extended results of the RESPECT trial originally presented at TCT 2016, as well as the findings from CLOSE and REDUCE that were presented in May at the European Stroke Organisation Conference.

Seeing these data in print may be what’s required to finally persuade naysayers that PFO closure has a role in this patient population, David Thaler, MD, PhD (Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA), co-author of one of the three papers, told TCTMD. “A lot of people in the medical community don’t follow subspecialties from conference data very carefully,” he said. “Though it was out there, it doesn’t mean anything to most people unless it's published or until it’s published, so now it’s more official.”

Physicians will now have a “firmer footing with which to give our advice to patients,” he said. Specifically, the message should be that there is an ongoing stroke recurrence risk that continues through time, “and for these young patients, the accumulated risk over time really might be something important.”

RESPECT, REDUCE, and CLOSE

One of the NEJM papers contains lengthy follow-up from RESPECT. As previously reported by TCTMD, the primary outcome from the original RESPECT trial, with an average follow-up of 2.1 years, showed no significant benefits of PFO closure over medical therapy (aspirin, warfarin, clopidogrel, or aspirin plus dipyridamole) in the intention-to-treat population, although signals of benefit were seen in the per protocol and as-treated patients.

In extended follow-up (mean 5.9 years), however, 18 patients in the PFO closure group and 28 patients in the medical therapy group experienced an ischemic stroke. When the analysis was restricted to strokes of unknown cause, recurrent stroke occurred in 10 versus 23 patients, respectively (HR 0.38; 95% CI 0.18-0.79). A key consideration, the authors point out, is the higher number of withdrawals in the medical therapy arm of the study, yielding 3,141 patient-years in the PFO closure arm and 2,669 patient-years in the medical-therapy group, potentially complicating interpretation of the results. Also of note, rates of venous thromboembolism were higher in the PFO closure group.

“The relative difference in the rate of recurrent ischemic stroke between PFO closure and medical therapy alone was large (45% lower with PFO closure), but the absolute difference was small (0.49 fewer events per 100 patient-years with PFO closure),” investigators by Jeffrey L. Saver MD (University of California, Los Angeles), write. Nevertheless, given the younger age of patients in the study, this benefit has “clinical relevance,” they conclude.

REDUCE, the second study published in NEJM last week, pitted the Gore Helex Septal Occluder or the Gore Cardioform Septal Occluder (both WL Gore & Associates) against medical therapy alone, 2:1, in 664 patients. In REDUCE, medical therapy consisted of aspirin alone, aspirin plus dipyridamole, or clopidogrel, with use of other antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants prohibited. As Lars Søndergaard, MD (Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark), and colleagues write, PFO closure was associated with significantly lower incidence of clinical ischemic stroke at 1.4% versus 5.4% (HR 0.23; 95% CI 0.09-0.62). Incidence of new brain infarctions was also significantly lower in the PFO closure group, although silent brain infarctions were no different.

The third study, CLOSE, by Jean-Louis Mas, MD (Hopital Sainte-Anne, Paris, France), and colleagues, randomized 663 patients with cryptogenic stroke to PFO closure, antiplatelet therapy alone, or oral anticoagulation. Here again, PFO closure (plus long-term antiplatelet therapy) also emerged the winner, at least compared with the antiplatelet therapy group. No strokes occurred over a mean of 5.3 years among those randomized to PFO, whereas 14 strokes occurred in the antiplatelet-only group (HR 0.03; 95% CI 0-0.12). Three strokes occurred in the anticoagulation group, but there was inadequate statistical power to compare these outcomes with the other two groups.

“Among patients 16 to 60 years of age who had had a recent cryptogenic stroke attributed to PFO with an associated atrial septal aneurysm or large interatrial shunt, the rate of stroke was lower with PFO closure plus long-term antiplatelet therapy than with antiplatelet therapy alone,” Mas et al conclude.

Of note, both CLOSE and REDUCE hinted at a higher risk of new onset A-fib after PFO closure.

Which PFOs to Close?

Last July, before the findings from any of the three papers published this week were even presented, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) took a tough stance on PFO closure by publishing recommendations suggesting that the procedure only be performed “in rare circumstances” outside of a research setting.

Shunichi Homma, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY), a cardiologist involved in crafting that AAN guidance, told TCTMD this week that while there is now “better evidence” showing a benefit of PFO closure in some patients, he remains unsure who the perfect patient is for this procedure.

Indeed, just how to choose which patients might benefit is broached in two editorials accompanying the studies. In the first, neurologist Allan Ropper, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), grapples with how to make sense of the conflicting PFO closure trial data, given that NEJM has previously published three earlier trials showing no benefit to the procedure. The answer, he suggests, may come from zeroing in on the characteristics of the PFO that would make embolic stroke possible—in other words, defining a PFO-related stroke based on features that are present as opposed to ruling out other causes of stroke based on what factors are “absent.”

On the basis of the newly published findings as well as data from the CLOSURE I, PC, and original RESPECT trials, he writes, “Restricting PFO closure entirely to patients with high-risk characteristics of the PFO may perhaps be too conservative, but the boundaries of the features that support the procedure are becoming clearer.”

Restricting PFO closure entirely to patients with high-risk characteristics of the PFO may perhaps be too conservative, but the boundaries of the features that support the procedure are becoming clearer. Allan Ropper

Thaler, speaking with TCTMD, was not completely willing to accept that PFO closure should only be considered in the presence of specific characteristics such as PFO size or presence of atrial septal aneurysm. “The data currently—and the FDA approval wording—are supportive of closing ‘cryptogenic stroke with PFO,’ not ‘cryptogenic stroke with big PFO only’ or not ‘cryptogenic stroke with PFO and an atrial septal aneurysm’ only. We don’t know that small shunts without atrial septal aneurysms are not also benefiting,” he argued, adding that the evidence available with regard to subgroups is “a bit messy.”

If PFO closure is restricted to patients with specific high-risk criteria, the worry for Thaler would be that cardiologists might potentially “withhold treatment from people who might benefit” from closure.

In a second editorial accompanying the NEJM papers, Andrew Farb, MD, Nicole Ibrahim, PhD, and Bram Zuckerman, MD, all FDA employees, highlight the criteria the agency used in approving the Amplatzer device, suggesting that these are the goal posts that physicians should be using.

Age is the most important, Farb, Ibrahim, and Zuckerman say, given that RESPECT included only patients between 18 and 60 years of age. Additionally, “because of the high prevalence of [PFO], the key to appropriate device use is comprehensive clinical assessment by both a neurologist and a cardiologist to confirm the diagnosis of ischemic stroke and exclude other possible causes,” they write. “Clearly, a deliberate, systematic assessment of the patient’s underlying conditions and the risks associated with ischemic stroke is needed before closure of a [PFO] can be recommended.”

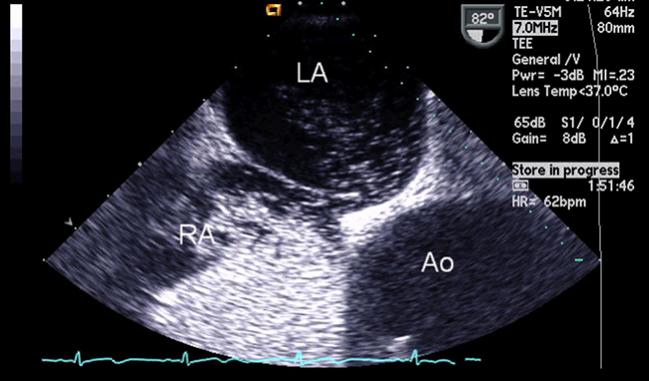

Imaging tests, including MRI, transesophageal echocardiography, and intracranial and extracranial arterial imaging as well as prolonged cardiac rhythm monitoring to diagnose atrial fibrillation and blood testing for coagulation disorders are all warranted to rule out other key causes of stroke, they noted.

Further information will come from the postapproval study mandated by the FDA at the time of the Amplatzer approval, Farb et al note.

A Changed Mind

To TCTMD, Thaler stressed the importance of the kind of careful work-up advocated by Farb et al’s editorial. “We don’t want every dizzy person to go to their primary care doctor and get [those symptoms] interpreted as a TIA without any other investigations, and suddenly [found to have] a PFO and then off they go to get it closed,” he said. “That would be irrational dispersion of this technology, and we are all for rationally dispersing it to people.”

Commenting on the new papers for TCTMD, Steven R. Messé, MD (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), a neurologist who led the AAN writing committee last year who has been outspoken about his qualms over PFO closure, now told TCTMD that the tides may have turned. “I’m personally very excited about the new data,” he said. “I think it’s very encouraging. It’s compelling evidence that PFO closure does reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.”

I think it’s very encouraging. It’s compelling evidence that PFO closure does reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.

Steven R. Messé

Adding that his practice will now change, Messé said, “In select patients where I think a PFO was the likely problem, I will recommend closure, and I expect that practice will change for many people in that direction.” That said, it’s rarely an “emergency” that a patient needs to have his or her PFO closed, so physicians should be careful in their decision-making process and make certain that other causes of stroke are ruled out. “I still feel strongly that there's a high risk for . . . misuse of these devices, and [in] the vast majority of patients who have a stroke and have a PFO, that the PFO is an innocent bystander,” he said.

Homma, for his part, hinted at the long-entrenched positions in the PFO closure debate, noting that it might be a challenge for some clinicians to remain unbiased in their discussions with patients about whether to proceed with PFO closure. He encouraged being “transparent” and prioritizing a “joint decision-making process.”

In the future, both Messé and Homma commented, additional study comparing PFO closure and anticoagulation might be insightful given that some evidence exists suggesting that anticoagulation might be more effective than antiplatelet therapy at preventing recurrent stroke. The FDA’s editorial also suggested the importance of continued surveillance of the Amplatzer occluder with a postapproval study.

As for the AAN recommendations, Messé said they do need to change and that the organization is “currently working on updating the PFO guideline.” While he can’t speak for all of the authors, he said, “I strongly suspect that they will conclude that physicians should recommend PFO closure for select patients.”

* Shelley Wood contributed to this article.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Mas J-L, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1011-1021.

Saver JL, Carroll JD, Thaler DE, et al. Long-term outcomes of patent foramen ovale closure or medical therapy after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377-1022-1032.

Søndergaard L, Kasner SE, Rhodes JF, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1033-1042.

Farb A, Ibrahim NG, Zuckerman BG. Patent foramen ovale closure after cryptogenic stroke—assessing the evidence for closure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1006-1009.

Ropper AH. Tipping point for patent foramen ovale closure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1093-1095.

Disclosures

- CLOSE was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health.

- RESPECT was supported by St. Jude Medical.

- REDUCE was supported by WL Gore & Associates.

- Mas reports receiving advisory board fees and lecture fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Daiichi Sankyo.

- Saver reports receiving grants and personal fees from St. Jude Medical during the conduct of the study, as well as grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work.

- Kasner reports grants from WL Gore & Associates during the conduct of the study.

- Ropper reports serving as a deputy editor of the New England Journal of Medicine.

- Thaler reports serving on the steering committee of the RESPECT trial.

- Farb, Ibrahim, Zuckerman, Homma, and Messé report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments