ACST-2: Carotid Stenting, Surgery Provide Similar Outcomes in Asymptomatic Patients

That opens the door to joint decision-making between patients and doctors to tailor the treatment plan, Edward Fry says.

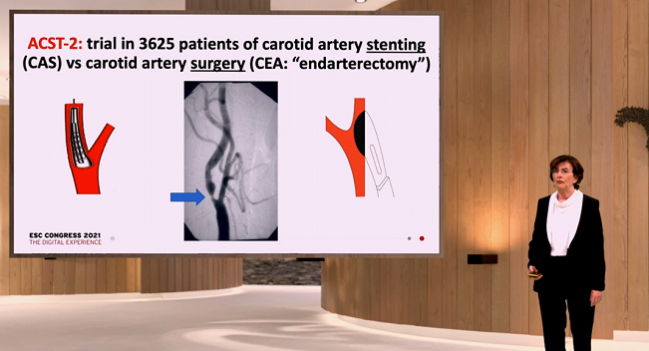

(UPDATED) Over the long term, patients with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis who are already on good medical therapy fare comparably well whether the artery is opened with stenting or surgery, according to results of the randomized ACST-2 trial, the largest trial of carotid revascularization yet completed.

Risk of disabling or fatal stroke within the periprocedural period was roughly 1% in the trial, with an annual rate of about 0.5% thereafter through 5 years and no significant differences between carotid stenting (CAS) and endarterectomy (CEA), according to Alison Halliday, MD (University of Oxford, England).

That represents an approximate halving of the stroke risk compared with what would be observed in the absence of either procedure, she reported during a Hot Line session at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2021.

The conclusion that can be drawn based on the findings of ACST-2 and prior trials of carotid revascularization, Halliday said at a media briefing, is that “for disabling and fatal stroke, CAS and CEA involve similar risks and similar benefits.”

Commenting for TCTMD, ACC Vice President Edward Fry, MD (Ascension Medical Group, Indianapolis, IN), said the results are reassuring because they support what has been shown in prior registry studies, bolstering the similarity in outcomes with stenting and surgery in a randomized fashion.

That “means that there really can be important joint decision-making discussions with patients and provides options and allows decisions to be tailored to the specific individual,” he said. One caveat is that there was a numerical increase in nondisabling strokes in the stenting arm of the trial, and it remains unclear whether that will have any impact on long-term dementia risk, he added.

The findings were published simultaneously online in the Lancet.

ACST-2 Findings

In introducing the study, Halliday underscored the importance of administering good medical treatment to patients with severe carotid stenosis, but noted that “adding CAS or CEA may also be appropriate.” Either will restore normal blood flow, albeit with some up-front risk—stenting has been shown to carry a higher periprocedural risk of nondisabling stroke, whereas endarterectomy comes with greater risks of nonfatal MI and cranial nerve palsy.

ACST-2 was designed to compare long-term outcomes between the two revascularization procedures in patients with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis who were deemed suitable for some type of intervention and who were uncertain about which to choose. Investigators randomized 3,625 patients with severe unilateral or bilateral carotid stenosis (60% or greater on ultrasound) across 130 centers in 33 countries. Aspects of care other than the assigned intervention were left to the discretion of the treating physician. Both groups received good medical therapy: 80% to 90% were received lipid-lowering, antithrombotic, and antihypertensive medications, Halliday reported.

Consistent with prior registry studies, roughly 1% had a disabling stroke or died in the periprocedural period, with no difference between the CAS and CEA arms. The rate of nondisabling stroke in the same time period, also consistent with previous studies, was higher in the stenting arm (2.7% vs 1.6%; P = 0.03).

After the first 30 days, and through an average follow-up of 5 years, the rate of fatal or disabling strokes was 2.5% in each trial arm (P = 0.91). The rate of any nonprocedural stroke was numerically but not significantly higher after CAS (5.2% vs 4.5%; rate ratio 1.16; 95% CI 0.86-1.57).

The investigators also combined the ACST-2 results with those from other carotid revascularization trials in both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, showing that the risk of nonprocedural stroke did not differ when comparing stenting versus surgery (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.91-1.32).

“With ACST-2 included, there is now as much evidence among asymptomatic as among symptomatic patients, and the findings in both types of patient are remarkably similar, with CAS about as effective as CEA at reducing the annual risk of stroke, at least for the first few years,” Halliday et al write. The ACST-2 participants will continue to be followed up to 10 years.

Choosing the Right Procedure

Addressing a question about choosing between CAS and CEA, Halliday noted that there is a difference in the length of the initial hospital stay (on average, a day less with stenting), and said cost might come into play in different parts of the world. She highlighted the importance of patient preference, but added that anatomy ultimately may push the patient toward one procedure or the other.

“You don’t really have as much of a choice as you might imagine,” Halliday said. “If you know that the competence of the people doing them both is equal, then the less-invasive procedure—providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following [the patients] for 10 years—is the more important. So if you were given a choice, most people would probably rather not have open surgery, providing that stenting was actually going to give them a good long-term result.”

Fry said the ACST-2 results indicate that either CAS or CEA would be a good option to bring to a patient-physician discussion about treatment. “There can be a certain comfort level in saying that by having a carotid stent, your overall outcome related to death and disabling stroke is going to be the same as if you had surgery, but you’d probably use that still to tailor the decision to the given individual,” he said, reiterating that the long-term consequences of nondisabling strokes are unclear. On the other hand, if a patient has a challenging anatomy for stenting, then physicians and patients can feel more comfortable opting for surgery.

Cardiovascular surgeon Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, PhD (University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany), commenting during a panel discussion after Halliday’s presentation, highlighted the increase in nondisabling strokes seen in the stenting arm of the trial, but said “the main conclusion from . . . the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe. It has to be done in order to avoid strokes. And obviously there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke.”

Interventional cardiologist Marco Roffi, MD (University Hospital of Geneva, Switzerland), noted several limitations of the trial, including a lower-than-planned number of patients; the long time it took to complete it (enrollment started in 2008); the likelihood that many centers recruited few patients, raising concerns about low procedural volumes; and the fact that recent technological improvements in carotid stenting, like proximal occlusion embolic protection and double-layer stents, were not used in a large percentage of cases.

Nonetheless, the trial indicates that “in centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

The Carotid Team

What is key, Fry said, is the multidisciplinary approach used in the study: all trial centers had a vascular surgeon and an interventionalist (potentially the same person), along with a neurologist (or stroke doctor) involved in patient care. That “may not be representative of general practice, and so I think underscoring the value of the multidisciplinary approach in terms of coming to the best decision for an individual” is important, he said.

Bernhard Reimers, MD (Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano, Italy), also highlighted the importance of what he called the “carotid team,” which allows for a collaborative decision made across specialties about the management approach. “Now the patients get treated the best possible way because there is dialogue between open and endovascular” physicians, he commented to TCTMD.

Fry said another important message to take away from the trial stems from the overall 18% mortality rate through 5 years, “which just shows you that these people have advanced atherosclerotic disease and obviously that portends a poor overall prognosis just in and of itself,” Fry commented. “So this trial points in the direction as to how to manage these patients, but represents a cohort of patients that have advanced atherosclerotic disease, and we need to redouble our efforts in terms of managing their overall atherosclerotic risk.”

Because all of the patients in the trial were deemed to have a need for a revascularization procedure, it can’t answer the question that has been debated within the carotid community in recent years—whether any intervention is necessary in the context of vastly improved medical therapy that has driven stroke rates lower than they were when the initial carotid intervention trials were performed. CREST-2, which encompasses two parallel trials separately comparing CAS and CEA to optimal medical therapy, may provide some insights, though it will not allow for direct comparisons between the two interventions.

Reimers acknowledged that medical therapy has improved over time, but said data from additional trials will be needed to establish whether modern medical therapy can match carotid interventions—either surgical or endovascular—in terms of long-term stroke risk. “Of course we do not have the third arm [in ACST-2] with best medical therapy, which now maybe is better, but anyhow, an incidence of 0.5% of major stroke per year is very low with significant carotid artery disease. So I think a procedure should be done.”

In the absence of new trial data pitting medical therapy against carotid revascularization in patients with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis, he said, “we need to advise them to get it treated, and we can advise them to do it either way, open or endovascular.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Halliday A, Bulbulia R, Bonati LH, et al. Second asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST-2): a randomised comparison of carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- ACST-2 is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and Cancer Research UK for the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Population Health, and received grants from the BUPA Foundation and National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme until 2013.

- Halliday is supported by the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Comments