Aspirate Contrast to Limit Acute Kidney Injury in Select Coronary Angiography Cases: Maybe, Maybe Not

Small, nonrandomized study of coronary sinus aspiration shows feasibility, but some question if this invasive approach is the best option.

New research supports the feasibility of using coronary sinus aspiration (CSA) to remove around one-third of the contrast given during coronary angiography—thereby potentially reducing the risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (AKI)—in selected patients. However, the fairly invasive procedure warrants highly skilled operators and cannot guarantee a benefit for any patient group, experts say.

Previous studies of CSA have been ongoing for at least a decade, but they have been limited by population size and procedural failures. At the same time, the incidence of contrast-induced AKI has declined due to better prevention measures and increased quality of contrast media, leaving some to question whether further investigation into a procedure like CSA is worthwhile, especially given that there’s still some mystery around the pathogenesis of contrast-induced AKI.

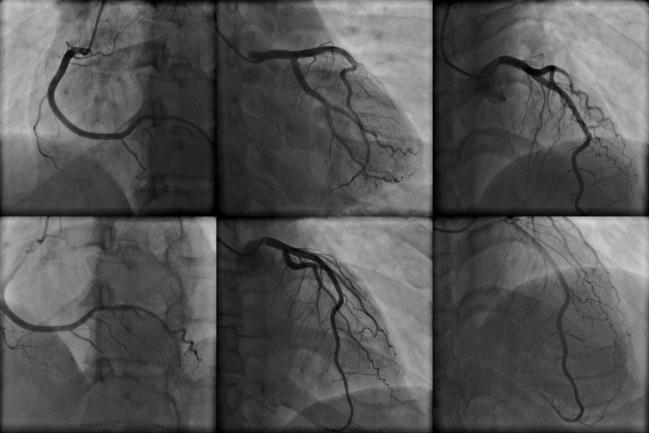

Nevertheless, Osama Ali Diab, MD (Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt), and colleagues published results online last week in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions from their nonrandomized study of 43 patients with diabetes and renal impairment who underwent coronary angiography with (n = 18) or without (n = 25) CSA via the subclavian or femoral venous approaches.

Procedural success was 100% in all CSA-treated patients, and there were no differences in type of coronary procedure and amount of contrast given between the study arms. CSA added about 20 minutes to the procedural time, but both the cannulation and fluoroscopy times were shorter in the last nine cases compared with the first. The procedure removed 39.35 ± 10.47% of the given contrast.

Postprocedure, the peak level of serum creatinine (SCr) as well as the percentage and absolute changes in SCr versus baseline were higher in the control group. Additionally, nine controls developed contrast-induced AKI compared with one patient given CSA.

Postprocedural Data

|

|

CSA |

Controls |

P Value |

|

Peak SCr, mg/dL |

2.01 ± 0.41 |

2.5 ± 0.58 |

0.001 |

|

Percent Change in SCr |

3.03 ± 16.24% |

18.06 ± 19.69% |

0.032 |

|

Absolute Change in SCr, mg/dL |

0.03 ± 0.3 |

0.37 ± 0.44 |

0.024 |

|

Contrast-Induced AKI |

5.55% |

36% |

0.028 |

On multivariate analysis, lack of CSA was the only independent variable associated with contrast-induced AKI (OR 9.26; 95% CI 1.03-83.26).

“The current study demonstrated the manual removal of contrast from the [coronary sinus] was feasible, safe, and could be done using commonly available equipment in the catheterization laboratories,” Diab and colleagues write. Specifically, they note, though the transseptal sheath used was not designed for the coronary sinus, it is “safe and effective” for CSA and was chosen “based on its favorable curves that would fit different [coronary sinus] takeoff angles and the possibility to rotate and manipulate with or without support by the dilator.”

Larger studies are needed to reproduce these findings, the authors acknowledge, adding, “Because the technique adds time and maneuvering to the angiographic procedure, it would be best used in a population with similar degree of risk, keeping into consideration that adequate hydration is still the standard preventative measure, regardless of any adjunctive procedures to prevent [contrast-induced] AKI.”

Several Limitations

In an editorial accompanying the study, Richard Solomon, MD, and Harold Dauerman, MD (University of Vermont, Burlington), write that CSA is not a new idea but is “certainly the most invasive method for limiting contrast exposure.” While the study shows a “dramatic reduction” in the incidence of contrast-induced AKI with CSA in comparison to past research, “several limitations warrant caution in being overly enthusiastic about this particular cure,” they comment.

Primarily, the editorialists highlight the following about the study: it was nonrandomized, patients were selected over 2 years, and the incidence of contrast-induced AKI was “unusually high” for controls. Lastly, they bring up the logistical complexities of the procedure itself. “Even if coronary sinus aspiration was to succeed without any excess complication risk, asking for a Heart Team approach to diagnostic coronary angiography may exceed the possibilities of most catheterization laboratory operations,” they write.

Nevertheless, Haim Danenberg, MD (Hadassah Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel), who served as the lead investigator in one of the first trials of CSA published in 2008, told TCTMD that he is “quite happy to see that efforts in this field are continuing.” The results are “definitely in accord with our preliminary findings. The main difference is the higher technical success in cannulation and staying stable within the coronary sinus,” he said in an email.

“[CSA] is a very invasive technique that cannot be applied to emergency patients, warrants operators that are highly experienced in coronary sinus cannulation, and prolongs the procedure significantly,” Danenberg added. “Therefore, it can be applied only in selected centers and reserved for very small group of patients.”

Future studies should focus on learning about the “additional factors” that affect contrast-induced AKI, he added. “Yet, reduction of injected contrast and mechanical removal of contrast before it reaches the kidneys are definitely the right way to go . . . [even though] it is cumbersome and prolongs the procedure.”

A Bigger Picture

On the other hand, David Kaye, MD, PhD (Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia), who served as the senior author on another CSA study published in 2010, told TCTMD in an email that not only does this study not support the routine use of CSA in selected patients to prevent contrast-induced AKI but that “at this stage there is no definitive data to suggest that [CSA] is broadly safe and effective.”

He said that his experience has shown that the procedure “requires considerable training,” which is “further limiting [the] likely enthusiasm for such an approach.”

Solomon and Dauerman bring the issue full circle by not ruling out a future for CSA while also maintaining that it might do some good in certain patients.

“There is a bigger picture that remains to be addressed in the context of causes and cures for [contrast-induced] AKI: although [contrast-induced] AKI is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, the prevention of long-term deterioration of kidney function remains the ultimate goal,” they write. To see the true effect of an intervention to prevent AKI, studies must go beyond the 48-hour time horizon to report on glomerular filtration rate and need for dialysis at 6 months and beyond, the editorialists urge.

While looking at novel biomarkers, limiting contrast exposure, and even removing contrast from the coronary sinus may lead to earlier detection of AKI, the editorialists add, “none of these advances help the patient sufficiently if these efforts do not translate into a preservation of long-term renal function and a reduction in the associated comorbidities that occur with progressive renal dysfunction that are likely triggered (at least, in part) by contrast exposure.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Diab OA, Helmy M, Gomaa Y, El-Shalakany R. Efficacy and safety of coronary sinus aspiration during coronary angiography to attenuate the risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in predisposed patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Solomon R, Dauerman HL. Acute kidney injury: culprits, cures, and consequences. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Ali Diab and Danenberg report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Solomon reports serving as a consultant for MediBeacon and PLS Scientific.

- Dauerman reports serving as a consultant for and receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

- Kaye reports being the co-founder and co-inventor of the CSA and pressure modulation technology developed by Osprey Medical.

Comments