CAC Scoring Is Predictive of Risk Across Races and Ethnicities

Black patients had a disproportionately higher risk of death at any CAC level compared with white patients.

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring is highly predictive of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality across a broad spectrum of races and ethnicities, new data suggest. The findings refute some earlier questions about whether the scoring has similarly robust prognostic implications for asymptomatic minorities as for white patients.

"The two main points we wanted to make here are that calcium scoring does 'work' in all races and that there might be some race/ethnicity differences in the prevalence of calcium, which we documented, but there might also be some complicated real-world differences in outcomes,” the study’s senior author, Michael Blaha, MD (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), told TCTMD in an interview. He said the findings have implications for clinicians, noting that he sees the study’s conclusion as a reason “to work even harder and pay extra attention to being aggressive with respect to [lifestyle] modification efforts for my minority patients.”

Traditionally, many patient groups have been poorly represented in Pooled Cohort Equations used to estimate 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk in clinical practice, note Blaha and colleagues in their paper published online October 2, 2018, in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

To TCTMD, Blaha said the new study adds to existing data that CAC scoring plays a critical role in assessing risk in minorities. In July, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and risks of adding nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors, including CAC screening, to traditional methods of risk assessment in asymptomatic adults.

“Very few things should be used in everybody,” Blaha said, adding that the USPSTF opinion on universal screening is not being challenged by the study, but rather the suggestion is that CAC may be more important in some patient groups than is currently appreciated.

“I think it plays an important role in assessing minority risk, especially in someone who hasn’t had their risk factors measured,” he said. “It's very helpful to use [CAC] with them to basically integrate all the risk exposures over their lifetime, including social determinants of health, and encapsulate that in the plaque burden. I have lots of patients who don't really know their family history and are getting their cholesterol checked for the first time in their lives.”

Commenting on the study for TCTMD, Mark Huffman, MD (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), said it is a “useful contribution” but noted that elucidating risk in minority patients is a complicated and imperfect process.

Minorities “have differences in access to care, life experiences, stress, racism, etc,” he continued. “Those are factors not captured in a database like this, but they factor into risk estimates.”

More All-Cause and CVD Mortality in Black and Hispanic Patients

Using data from the CAC Consortium and led by Olusola A. Orimoloye, MBBS (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine), the researchers assessed predictive value of CAC in 38,277 white, 1,621 Asian, 977 black, and 1,349 Hispanic individuals who were followed for events for a median of 11.7 years.

The distribution of CAC by self-reported race/ethnicity demonstrated small but significant differences. Black patients had the highest prevalence of CAC (56.1%), followed by white (55.8%), Hispanic (54.0%), and Asian individuals (51.0%). Compared with women of other race/ethnicity groups, black women had a greater prevalence of calcification, while white and Hispanic men had more CAC prevalence than men of other race/ethnicity groups.

Across all categories of CAC scoring, including CAC 0, black patients had a disproportionately higher rate of all-cause and CV disease death than other race/ethnicity groups, followed closely by Hispanic participants. For example, at a CAC score of 100-399, the rate of all-cause death for black patients over the study period was 18.4% compared with 11% for Hispanic and 6.8% for white patients. The lowest rates of all-cause death were seen in Asian patients across all CAC categories.

There was a trend toward a greater hazard of death with increasing levels of CAC (vs CAC 0) within each race/ethnicity group. However, the gradient of all-cause and CV disease mortality risk at increasing CAC score was steeper in black and Hispanic individuals than in white patients. Additionally, in multivariable analysis adjusting for the effect of race/ethnicity, black and Hispanic patients continued to have greater all-cause and CVD mortality risk compared with white study participants, while Asian individuals had similar mortality risk compared with white patients.

Application of Risk Predictors in the Real World

Orimoloye and colleagues note that the findings are important in light of recent guideline recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the USPSTF to use risk-prediction tools to guide individual clinical decisions about preventive therapy.

To TCTMD, Blaha admitted discussions about long-term risk can be challenging.

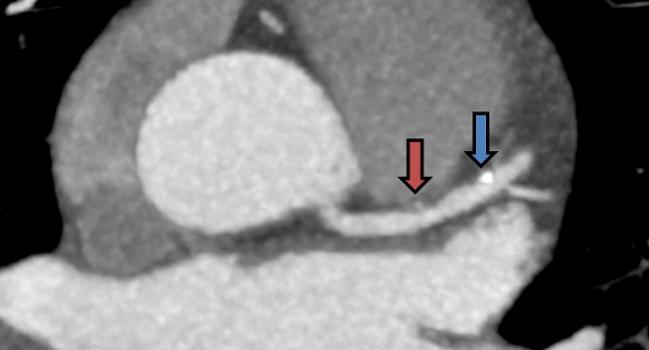

“On a couple of occasions, I’ve told a patient, ‘You’ve got a 15% chance of heart attack in the next 10 years,’ and they look at me and say ‘You mean there’s an 85% chance I'll be fine in the next 10 years and you want me to take medicine?’ But you get a different reaction when you turn around the monitor and show them an image of their heart and say: ‘This signifies plaque.’ That's the kind of [discussion] we can have and do have around CAC scores that can lead to patients taking medicine and having a better understanding of risk.”

Huffman said he uses the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) calculator frequently in his practice and agreed that presenting risk information is a good opportunity for patient education.

“I think we’re still in the early stages of understanding the best way to communicate this information to patients,” he said in an interview with TCTMD. Like Blaha, he pointed out that the way an individual patient digests his or her risk information is highly variable and subject to their level of health numeracy.

“For many patients, starting preventive therapy is driven by the concept of disutility, meaning what would it take for me to want to start or intensify a medication? What would be the risk reduction that I would need to see, or the number of years of my life saved? For some patients one extra day of life is all they need to know, but for others they might need to gain an extra decade before they take a medication with potential side effects that they have to take for the rest of their life,” Huffman observed. “Risk calculation sets that decision up but doesn’t mean there is an automatic provision of a prescription.”

Photo Credit: ©2015 American College of Cardiology. Used with permission from the American College of Cardiology

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Orimoloye OA, Budoff MJ, Dardari ZA, et al. Race/ethnicity and the prognostic implications of coronary artery calcium for all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: the Coronary Artery Calcium Consortium. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010471.

Disclosures

- Orimoloye reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Blaha reports receiving support for the study from a National Institutes of Health award.

- Huffman reports serving as senior program advisor for the World Heart Federation’s Emerging Leaders program, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis; research support from One Brave Idea, sponsored by the AHA, Verily, and AstraZeneca; and serving as an associate editor for JAMA Cardiology.

Comments