CHAP: Better Blood Pressure Control, Better Pregnancy Outcomes

Tighter BP control to a target of less than 140/90 mm Hg did not cause any harm to mom or baby, say researchers.

WASHINGTON, DC—Treating pregnant women with mild chronic hypertension to a more aggressive blood-pressure target is associated with better pregnancy outcomes—and is not associated with any harm to fetal growth—when compared with usual care, according to a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) study.

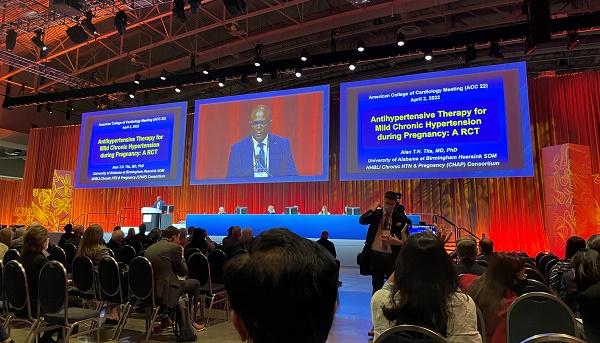

The Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) trial is one of the largest, most diverse studies conducted in pregnant woman to date and addresses a major clinical question that has been debated for decades, lead investigator Alan T. Tita, MD, PhD (University of Alabama at Birmingham), said during a press briefing at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2022 Scientific Session.

Going forward, Tita believes the study will have an immediate impact on how physicians care for their pregnant patients and others didn’t disagree, hailing the NHLBI study as an important and long-awaited clinical trial.

“Pregnant women are understudied in many, many ways, but we definitely needed this data in hypertension to help guide our treatment,” said Mary Norine Walsh, MD (Ascension St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, IN), who commented on the study during the press conference. “Maternal mortality in the United States is rising, and it’s higher than most developed countries.”

Walsh pointed out that more than half of patients randomized in the trial had government-assisted insurance or Medicaid and that 48% of participants were Black, a particularly vulnerable patient population. “We’re all going be very busy now following these patients closely to make sure their blood pressure is at goal,” said Walsh.

The results of the CHAP study were presented today during the late-breaking clinical trial sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Chronic Hypertension in Pregnant Women on the Rise

In the United States, chronic hypertension affects roughly 2% of pregnant women—“and it is rising due to older age and obesity at childbirth,” said Tita—and disproportionately affects Black women. It is associated with a higher risk of preeclampsia, placental abruption, preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, or perinatal death, according to the investigators. Additionally, chronic hypertension is associated with a significantly higher risk of maternal death, heart failure, stroke, pulmonary edema, or acute kidney failure.

Outside of severe acute hypertension, however, the treatment of high blood pressure with antihypertensive agents in pregnant women is controversial. More than 20 years ago, a meta-analysis published in the Lancet suggested that treatment-induced reductions in maternal mean arterial pressure adversely affect fetal growth. A later study, the CHIPS trial comparing “tight” versus “less tight” blood pressure control in women with mild hypertension, didn’t show any adverse effects on fetal growth, but the study was underpowered to look at clinical outcomes.

In severe hypertension—defined as ≥ 160/110 mm Hg—there is a consensus that treatment is required, but in those with mild chronic hypertension—defined as more than 140 mm Hg systolic, more than 90 mm Hg or higher diastolic, or both—there is wide variation across international guidelines. Randomized controlled trials for the treatment of hypertension in pregnant women are few, and those that are available tend to be underpowered and limited in design.

With that background, investigators launched the open-label NHLBI-funded CHAP study. For the trial, 2,404 pregnant women with mild chronic hypertension carrying a single fetus of gestational age of 23 weeks or less were randomized to antihypertensive medication to lower blood pressure to less than 140/90 mm Hg. The control arm did not involve treatment unless severe hypertension was detected (≥ 160 mm Hg systolic or ≥ 105 mm Hg diastolic pressure).

Patients in the active-treatment group were prescribed first-line antihypertensive therapy with labetalol or extended-release nifedipine (or amlodipine or methyldopa if preferred by the patient, but these were not provided by the study investigators) at the maximally tolerated doses. A second agent was added if necessary.

The primary outcome of the study, which was a composite that included preeclampsia with severe features, medically indicated preterm birth at less than 35 weeks’ gestation, placental abruption, or fetal or neonatal death, occurred in 30.2% of women treated to the blood-pressure target of less than 140/90 mm Hg and 37.0% of those treated to usual care. The incidence of preeclampsia was 24.4% in the active-treatment arm versus 31.1% in the control group (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.69-0.89). The incidence of preterm birth was also significantly lower among women randomized to active treatment—27.5% vs 31.4% (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77-0.99).

Roughly 15 women with chronic hypertension would require treatment with antihypertensive therapy to prevent one adverse pregnancy outcome, said Tita.

In terms of safety, there was no increased risk of small-for-gestational-age births (below the 10th percentile): 11.2% in the active-treatment group vs 10.4% in the control arm (P = 0.76). Additionally, there was no difference in the risk of small-for-gestational-age birth weights below the 5th percentile. Similarly, there was no increased risk of serious maternal or severe neonatal complications between the two groups.

In an accompanying editorial, Michael Greene, MD, and Winfred Williams, MD (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston), say that “most exciting finding in this trial (possibly the result of the large enrollment) is the apparent reduction in the incidence of various measures of preeclampsia in the active-treatment group, findings that have not been observed in eight previous randomized trials, including CHIPS.”

Getting the Message Out There

To TCTMD, Tita said there is now much work to do in terms of disseminating the results to practicing physicians, noting that they’ve been in touch with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists about their results.

Tita also pointed out that all the ob-gyns involved in the study, as well as those who practice at his hospital, are comfortable prescribing antihypertensive medications for patients with hypertension. Instead of referring these patients to cardiologists or internists, Tita believes most ob-gyns could continue to manage patient care, at least those who manage high-risk patients. However, ensuring these specialists are comfortable treating hypertension might involve further training, something the researchers are beginning to consider.

Athena Poppas, MD (Lifespan Cardiovascular Institute and Brown University, Providence, RI), who discussed the study following the presentation, called CHAP a practice-changing clinical trial, one that wasn’t easy to perform given some of “logistical and ethical concerns” around conducting trials in pregnant women.

“These studies just don’t get done,” she told TCTMD. “Most of the guidelines had suggested that unless the patient was in the severe range, we’d allow their blood pressure to be higher than in the nonpregnant state, even though we know the risk of mortality and morbidity was high.”

Poppas, immediate past president of the ACC, said it will be important for primary care physicians and cardiologists managing women of child-bearing age with chronic hypertension to switch them to labetalol or nifedipine before pregnancy. “If they’re going to become pregnant, we want to get them off the ACE inhibitor so that we can make sure they’re controlled before becoming pregnant,” she said. ACE inhibitors are contraindicated during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

Finally, Poppas noted that nearly 30,000 patients were screened to achieve randomization and questioned the generalizability of the findings. In response, Tita said that many women with chronic hypertension were excluded from the study because their blood pressure was too low at the time they were screened.

“Many patients who have chronic hypertension may have their medication stopped, and it takes a while for their blood pressure to go back to the baseline levels,” said Tita. “Over 65% of patients excluded were those who had a prior diagnosis of chronic hypertension but didn’t meet the entry threshold. In terms of generalizability, I do think the results are applicable to a broader group that the just approximately 10% that ended up in this study. Going forward now, not everyone will have their medication withdrawn during pregnancy and or findings suggest that they’ll most likely have benefit coming in on treatment.”

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggress, K, et al. Treatment for mild chronic hypertension during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Greene MF, Williams WW. Treating hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Tita, Walsh, and Poppas report no conflicts of interest.

Comments