Coronary Calcium IDs Higher Heart Disease Risk Even in Younger Adults

Presence of the biomarker can help inform primary prevention strategies, but not everybody should run out to get a CT scan, an author says.

Adults between the ages of 32 and 46 who have even a small amount of coronary artery calcium (CAC) have an elevated risk of coronary heart disease events before they reach age 60, an analysis of the CARDIA study demonstrates. Moreover, all-cause mortality risk is higher in those with at least moderate amounts of calcium.

“We now have a biomarker in the form of coronary artery calcium that can identify people at very high risk early in adult life and in middle-adult life that we can then use to further improve our prevention strategies,” lead author John Jeffrey Carr, MD (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN), told TCTMD, noting that traditional assessments using office-based measures can underestimate cardiovascular risk in some people.

The presence of CAC gives a clear sign that the disease process has already begun, allowing patients and physicians to have a more informed discussion about the need for primary prevention, he said. “The tenet of prevention is that we ratchet up the amount of prevention based on the individual’s risk.”

He added that the study, published online February 8, 2017, ahead of print in JAMA Cardiology, does not mean that everybody in the included age group should get a CT scan to look for CAC. Rather, Carr and his colleagues recommend using a tiered screening strategy that starts with using traditional risk factors to identify patients most likely to have calcium and then performing the scans to further clarify their risk.

An additional implication of the findings, Carr said, is that they “will allow us to more accurately manage incidentally detected coronary calcium” on chest CTs performed for other indications. A change that can be made to clinical practice right now is to inform patients when calcium is detected on a scan so they can talk to their doctors about the possibility of getting started on prevention measures after dealing with the primary problem, he said.

Leslee Shaw, PhD (Emory University, Atlanta, GA), who was not involved in the study, told TCTMD that the idea of scanning for CAC in such a young population is controversial, but—like Carr—pointed out that widely used clinical assessments may underestimate the degree of subclinical atherosclerosis. This analysis, she said, shows that even in individuals as young as 40 there are subgroups of patients who are vulnerable to early vascular disease and are at risk for premature coronary events and death.

Shaw added that CAC was relatively uncommon in this study, even at the latest time point, but suggested that the authors’ strategy of using a collection of clinical risk factors to identify higher-risk patients was a good start toward finding a subgroup in which you might consider using calcium scoring.

Centers in some parts of the country are more aggressive than others in terms of using screening tools—including calcium scoring and others—to target prevention efforts, she said, and for those systems such a tiered approach “would fit nicely into what you normally use.”

In particular, patients who are on the cusp of moving into a cardiovascular risk category that would make them candidates for treatment might represent a population in which calcium scoring might be used, especially at younger ages.

“If we’re going to get into the paradigm of prevention and preventable disease and preventable death as a population, then you have to think about early detection,” Shaw said. “That’s the paradigm that we use in other areas, particularly around cancers like breast cancer. Early detection leads to improved life. We don’t have evidence to say that, but that’s something we think about as a culture and I think it makes sense if that person has an elevated risk.”

More Calcium Equals Higher Risk

Prior studies have established a link between CAC and risks of coronary heart disease and other types of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and older adults, but there are limited data on the prognostic value of CAC in younger adults.

For the current study, the researchers looked at data from CARDIA, a prospective study of black and white people recruited at ages 18 to 30 years in 1985 and 1986. CAC was measured by noncontrast CT at 15, 20, and 25 years of follow-up; the number of patients screened at each time point ranged from 3,043 to 3,189.

The prevalence of CAC was 10.2% at the first time point, 20.1% at the second, and 28.4% at the third, with a corresponding increase over time in the geometric mean Agatston score among patients with at least some CAC (from 21.6 to 59.1 to 144.4).

The mean clinical follow-up for patients who had been screened at 15 years (average age 40.3) was 12.5 years. Those who had any amount of CAC detected were more likely to have a coronary heart disease event (HR 5.0; 95% CI 2.8-8.7) or cardiovascular disease event (HR 3.0; 95% CI 1.9-4.7) over that interval. The association with coronary heart disease strengthened along with the burden of calcification but remained significant even at the lowest levels of CAC.

For patients with a CAC score of at least 100, there was an elevated risk of all-cause death (HR 3.7; 95% CI 1.5-10.0). That finding was based on 13 deaths, of which 10 were due to coronary heart disease.

To explore the idea of using clinical risk factors to identify a high-risk group of patients to target with calcium scoring, the researchers developed a CAC prediction score and divided participants into deciles. The prevalence of CAC was 4.2% in patients with the lowest scores and 67.8% in those with the highest.

The investigators found that a strategy of targeting only those patients with a score above the median would capture 77.3% of patients with CAC and 95.5% of patients who had coronary heart disease events during follow-up. The approach would reduce the number of people recommended for screening by 50% and the number needed to image to find one person with CAC from 3.5 to 2.2.

Next Steps

The authors note that the 2013 recommendations on risk assessment from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association “include screening for CAC as an option for assessment of risk of CVD in individuals for whom uncertainty exists; recent reports further support this application. Coronary artery calcium score thresholds of 100, 300, and 400 or age-based percentiles have commonly guided recommendations; however, in light of our findings, these recommendations might be reconsidered in favor of lower thresholds in middle-aged and younger adults.”

Carr said that moving forward it would be ideal to have a randomized trial showing that screening for CAC and modifying management based on that can reduce overall event rates. He and his colleagues have been working to get such a trial funded, but they have not yet been successful. Nonetheless, he said, that “shouldn’t keep us from moving forward with doing standard of care and best practices to the best of our ability.”

In an accompanying editorial, Ron Blankenstein, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), and Philip Greenland, MD (Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, IL), point out that Mendelian randomization studies suggest that longer exposure to lower LDL cholesterol levels is associated with lower risks of coronary events, “thus supporting the biologically plausible hypothesis that, in selected individuals, earlier initiation of lipid-lowering therapies may provide greater benefit.”

“However,” they continue, “expansion of statin treatment to younger individuals may expose many individuals to unnecessary harm, and thus while it is appealing in many ways, it requires better methods to identify at-risk individuals.”

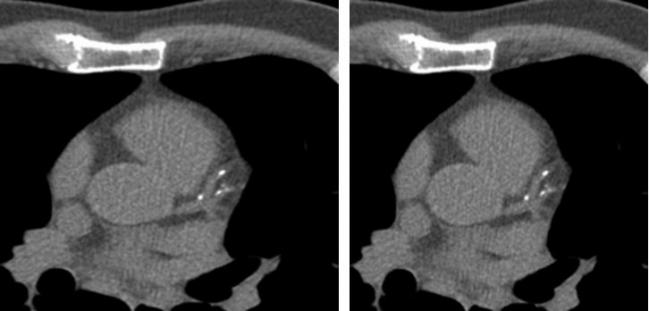

Photo Credit: Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Carr JJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Terry JG, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium in adults aged 32 to 46 years with incident coronary heart disease and death. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Blankenstein R, Greenland P. Screening for coronary artery disease at an earlier age. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to Vanderbilt University and Wake Forest University. CARDIA is supported by contracts from the NHLBI and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging.

- Carr, Blankenstein, Greenland, and Shaw report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments