Device Embolization: Tools and Training Essential to Avoid Worst-Case Scenarios

A state-of-the-art review proposes an algorithm for handling this complication as well as tips for a percutaneous removal “toolbox.”

Despite meticulous planning and safety checks, device embolization during structural heart interventions still—infrequently—occur. A new state-of-the-art review offers advice for operators looking to prepare themselves and their team for handling the dreaded complication.

The published literature on structural heart disease interventions describes device embolization in 1% or less of all procedures. According to lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD (West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV), the rare nature of these events also means there is little guidance for clinicians about what they need to do to safely and successfully remove or reposition an embolized device.

Just how much device embolization affects outcomes is also unclear, with limited data coming from the PARTNER trial, single-center reports, and European registries, according to the paper's authors. In PARTNER, for example, patients who experienced device embolization had a 1-year mortality rate more than two times higher than those who did not (HR 2.68; 95% CI 1.34-5.36).

"The main purpose of this paper is that it highlights the issue. It's an issue that nobody wants to talk about,” he said in an interview with TCTMD. “It stemmed from the need I had to learn about it, and then it evolved into a paper that I felt others could benefit from.”

Alkhouli and colleagues created algorithms to guide operators, step-by-step, through the management of device embolizations of transcatheter aortic valves and septal/left atrial appendage and vascular occluders. The paper also lists common scenarios that can lead to device embolizations, as well as all of the retrieval equipment currently available on the US market that might come in handy for structural interventions. The paper further explains which devices should be in the cath lab’s emergency “percutaneous retrieval toolbox.”

“[Device embolization] is something that we don't often see and, like the authors state, it’s not something you ever get formal training on as a structural heart fellow. Even if you do, it's not as if you're seeing a ton of different cases with these particular complications,” noted Hemal Gada, MD (UPMC Pinnacle, Harrisburg, PA), who commented on the paper for TCTMD.

“Some of these complications are not common, but when they do occur, having a tool kit to be able to handle them is absolutely essential. If you do enough volume, you're going to see these complications,” he added.

The review paper was published online today in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Planning and Preparation: Keys to Success

Alkhouli noted that most device embolizations can be handled successfully. However, being prepared for them by having retrieval devices readily available and knowing how to use them is another matter.

Gada agreed. “I don't think these are tools that are at the ready in most instances. They may be stored in the cath lab, and it may take a little bit of digging around to get them out.” He added that running “fire drills” every 6 months to a year can help to ensure that everyone in the cath lab knows where the emergency toolbox is and how the individual components of it are used.

I don't think these are tools that are at the ready in most instances. They may be stored in the cath lab and it may take a little bit of digging around to get them out. Hemal Gada

Snares, for example, can be used in many scenarios and should be part of any percutaneous retrieval toolbox, according to Alkhouli and colleagues.

“Due to the variable introducer sizes, working lengths and diameters, and wire compatibilities, operators should familiarize themselves with one or two snare systems that are kept routinely updated in their catheterization laboratory inventory,” they write. “The choice of snare type and size largely depend on the type and the location of the embolized devices, and the planned retrieval technique.”

Other tools likely to be useful in device embolization situations include bioptomes and forceps, adjustable electrical mapping catheters and large lead removal systems for electrophysiology procedures, and basket-based ureteral stone extractors for interventional radiology procedures.

“Steerable sheaths and pigtail catheters can also be invaluable in reaching and disimpacting embolized devices and should be included in the retrieval tool kit,” Alkhouli and colleagues add.

They also recommend maximizing safety during retrieval procedures by ensuring adequate anticoagulation, becoming comfortable with retrieval techniques and/or soliciting assistance from experienced colleagues, using a multidisciplinary approach involving appropriate specialists as soon as the complication occurs, and setting a time limit after which percutaneous attempts must be aborted and the procedure converted to surgery.

Training Essential, but Largely Unavailable

Gada said one of the most important aspects of the review paper is that it draws attention to the fact that training in how to handle catastrophic device embolizations is lacking both during fellowship and in clinical practice.

“Time has come for a collaborative effort between structural interventionalists and device manufacturers to develop simulator models that can be integrated into fellowship and new users training programs to minimize the risk of device embolization and optimize its management,” Alkhouli and colleagues write. To TCTMD, Alkhouli said flow simulators “are the perfect choice to train on how to use snares.” In addition to learning how and when to use the devices, a simulator can also help operators master their retrieval techniques safely and avoid causing undue injury, he said.

“You could tear tissue, you could dissect the aorta, you could have a perforation that could potentially lead to pericardial tamponade,” Gada noted. “All of those things matter, so . . . you've got to know the anatomy of the patient and what happens when you snare a device.”

Other options for gaining familiarity with how the tools work, according to Alkhouli and colleagues, are for fellows to be involved in procedures where elective snaring is used, such as arteriovenous loops in paravalvular leak closure; by cross-training with vascular specialists who routinely perform snare removal of temporarily implanted devices such as vena cava filters; and by participating in bench retrieval experiments using in vitro models.

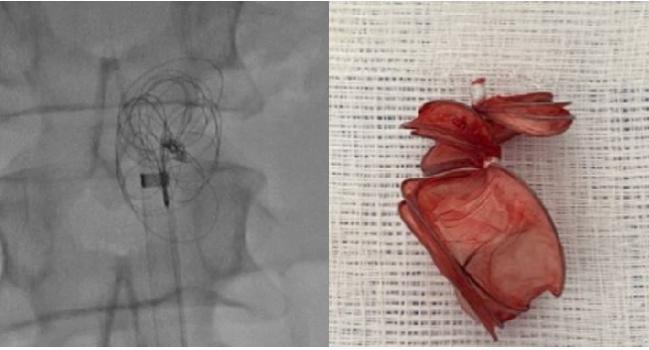

Photo Credit: Mohamad Alkhouli. An embolized Cardioform ASD occluder (Gore), shown on imaging, then after device retrieval.

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Alkhouli M, Sievert H, Rihal CS, et al. Device embolization in structural heart interventions: incidence, outcomes, and retrieval techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2019;12:113-126.

Disclosures

- Alkhouli reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Gada reports consulting for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Edwards, and Abbott.

Comments