FAME Published: FFR Guidance Improves Outcomes in Multivessel Disease

In patients with multivessel coronary disease who are angiographic candidates for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), measuring fractional flow reserve (FFR) in each artery and restricting stenting to ischemia-producing lesions results in a lower risk of major adverse events at 1 year, according to a study published in the January 15, 2009, issue of The New England Journal of Medicine. It also significantly reduces the number of stents implanted, contrast exposure, and overall cost.

Results of the FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Guiding PCI in Patients with Multivessel Evaluation) trial were first presented in October at TCT 2008.

Nico H.J. Pijls, MD, PhD, of Catharina Hospital (Eindhoven, The Netherlands), and an international team of researchers randomly assigned 1,005 patients with multivessel disease at 20 centers to undergo PCI based on angiography alone (n = 496) or based on FFR guidance in addition to angiography (n = 509). In the angiography group, lesions with at least 50% stenosis were routinely implanted with drug-eluting stents. In the FFR-guided group, only those that scored 0.80 or less—indicating ischemia—received stents.

FFR, defined as the ratio of maximal blood flow in a stenotic artery to normal maximal flow, was measured by a guidewire with a pressure sensor at the tip (Radi Medical Systems, Uppsala, Sweden). Stents were not implanted in 513 (37.0%) lesions in the FFR group since the occlusions were not ischemia-producing (FFR value ≤0.80).

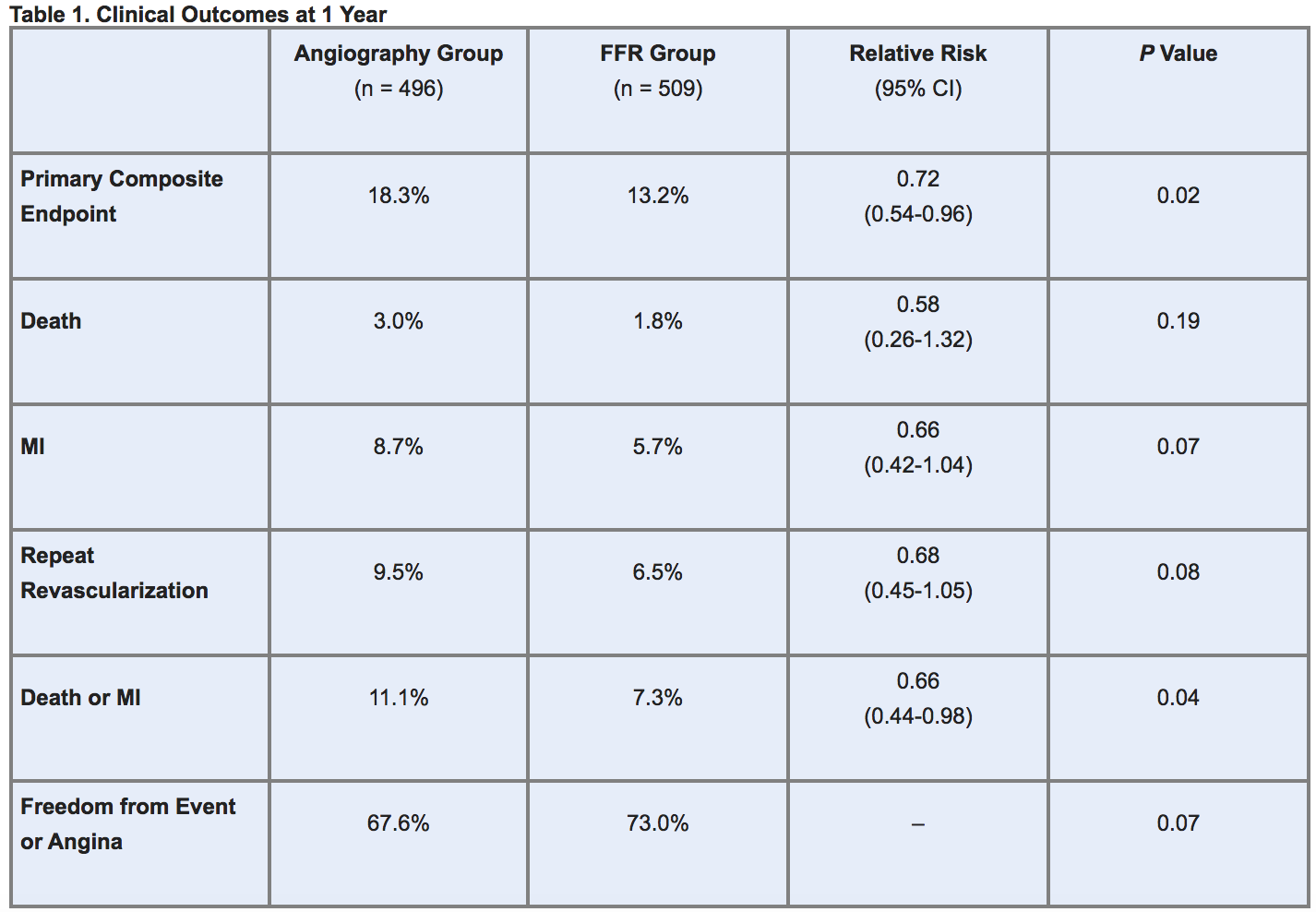

At 1-year follow-up, the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), and repeat revascularization) occurred more frequently in angiography-guided patients. Though not a prespecified endpoint, the combined rate of death or MI was also significantly higher in the angiography arm. In addition, among these patients, there was a trend toward higher rates of MI or repeat revascularization, while in the FFR arm patients were more likely to remain free from an adverse event or angina (table 1).

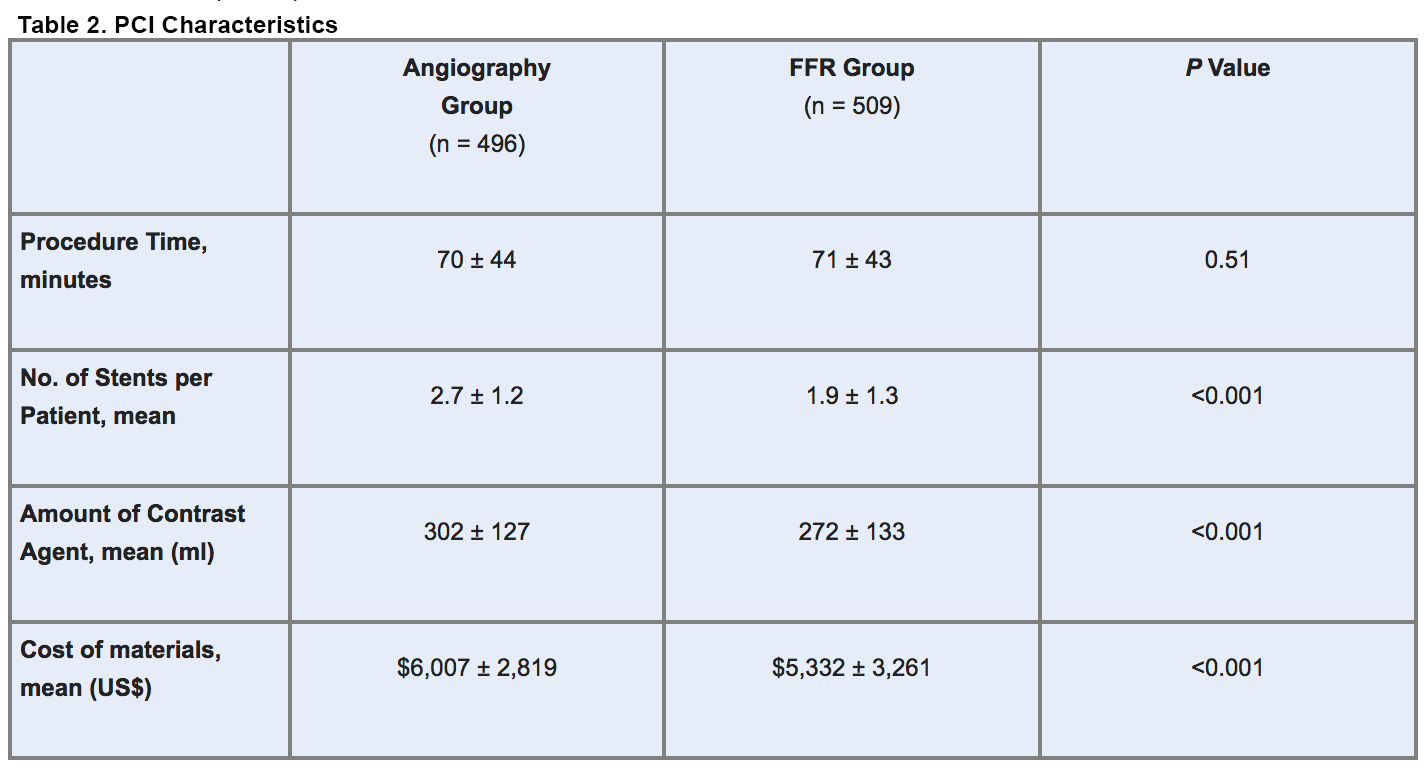

Without prolonging procedure time, FFR testing conferred several other advantages, including reductions in:

- Number of stents implanted per patient

- Amount of contrast exposure

- Material costs (table 2)

The fact that 89.6% of patients in the FFR-guided group had at least 1 stenotic lesion with an FFR of 0.80 or less indicates that the strategy was used in an unselected population, the authors note, since in patients with intermediate stenoses (40% to 60%) only about 35% have an FFR score that indicates ischemia.

The investigators calculated that given the 5% reduction in absolute risk observed in this study, 1 major adverse event can be prevented for every 20 patients whose treatment is guided by FFR.

Improving the Risk/Benefit Ratio

Explaining the benefit of the FFR strategy, the authors write that “performing PCI on all stenoses that have been identified by angiography, regardless of their potential to induce ischemia, diminishes the benefit of relieving ischemia by exposing the patient to an increased stent-related risk, whereas systematically measuring FFR can maximize the benefit of PCI by accurately discriminating the lesions for which revascularization will provide the most benefit from those for which PCI may only increase the risk.”

The investigators acknowledge that with longer follow-up, untreated lesions in the FFR group may progress and lead to adverse events. However, they say, “from previous studies it is known that persons who have lesions with an FFR of more than 0.80, if optimally treated with medication, have an excellent prognosis, with an event rate of approximately 1% per year up to 5 years after measurement.”

In an accompanying editorial, Stephen G. Ellis, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH), writes that the FAME investigators are likely “on to something” by underlining the need to selectively target only those lesions that are clearly associated with ischemia. He noted, however, that the researchers were less than clear about whether stenting decisions in the angiography-guided group might have, in some cases, included input from stress testing.

Motivating FFR Use: Data—and Scrutiny

Sunil Rao, MD, of Duke University Medical Center (Chapel Hill, NC), said the magnitude of the benefit provided by FFR guidance would likely spur increased adoption of the technique. “As a broad strategy, I think FFR really is something that cath labs need to do a lot more of, particularly [in light of] the recent publication of appropriateness criteria,” he commented in a telephone interview with TCTMD, “[Interventionalists] are really being scrutinized now, and the more you can do to justify your stent, the better off you are.”

Currently FFR is used in only a very small percentage of cases, according to Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center (New York, NY). But, he said in a telephone interview with TCTMD, the FAME findings are “solid” and “from speaking to many people, I think the use of FFR is significantly increasing on the basis of this study.”

He noted, however, that “the way they did FFR in this trial was probably more comprehensive than [the way] most people will use it. They performed FFR in any vessel they were considering treating. I think most people in the real world will use it to assess intermediate-type lesions . . . . Whether these results can be replicated with a more selective use of FFR is not known.”

Dr. Rao added that FFR is designed for use primarily on lesions with visually assessed intermediate stenoses. In that setting, “if you have a patient who has a convincing anginal story [but] a normal stress test, . . . FFR is extremely helpful because you’re able to evaluate the arteries at the lesion level” to determine which are functionally significant.

The technique is both safe and relatively straightforward, Dr. Stone said, although “there are some tricks in learning how to use it.”

Dr. Rao agreed, noting that an attractive aspect of FFR is that unlike other functional testing methods, interventionalists can do it themselves. “I can evaluate a lesion right in the cath lab, get the results in real time, and make a decision [regarding stenting] in real time,” he said.

Study Details

CAD was defined as 50% or greater stenosis in at least 2 major epicardial arteries. Patients who had angiographically significant left main disease or had suffered an ST-segment elevation MI within 5 days were excluded. Baseline characteristics of the patients in the 2 arms were similar, as were the number of lesions and lesion and vessel dimensions. All patients were treated with aspirin and clopidogrel for at least 1 year after PCI.

Sources

Tonino PAL, De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2009;360:213-224

Ellis SG. Refining the art and science of coronary stenting. N Engl J Med 2009;360:292-294.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by unrestricted research grants from Radi Medical Systems and Stichting Vrieden van het Hart Zuidoost Brabant. Medtronic provided limited financial support to some centers

- Dr. Pijls reports receiving an institutional research grant from Radi Medical Systems.

- Dr. Ellis reports receiving consulting fees from Cordis, Boston Scientific, and Abbott Vascular; lecture fees from Cordis; and grant support from Centocor/Eli Lilly, Celera Diagnostics, Cordis, and CadioDx.

- Dr. Rao reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Dr. Stone reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments