‘Hub and Spoke’ Model Promises to Improve Access to PCI for STEMI in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Despite the significant challenges of poverty and transporting patients in rural areas, researchers are hopeful that the concept can be expanded.

An innovative model of a STEMI system of care could be an important tool for improving survival in countries such as India that have limited healthcare infrastructure, widespread poverty, and poor accessibility to emergency medical services (EMS).

In a report published online last week in JAMA Cardiology, investigators demonstrated that their “spoke and hub” model more than tripled the percentage of patients who underwent primary PCI and improved mortality at 1 year in a rural, impoverished region. The concept, they say, could hold potential for middle- and low-income countries where treatment for and survival from STEMI are suboptimal.

For the TN-STEMI program, researchers led by Thomas Alexander, MD (Kovai Medical Center and Hospital, Coimbatore, India), studied outcomes of 2,420 patients living in the Tamil Nadu region of southern India who required treatment for STEMI from June 2013 through June 2014.

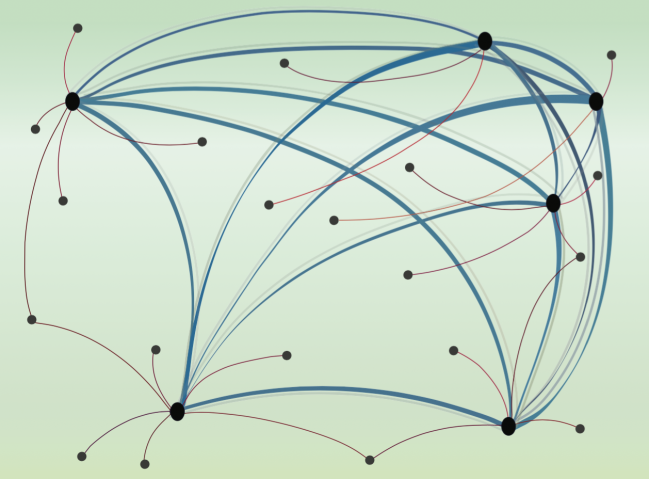

The model consisted of four hub hospitals linked to 35 peripheral spoke hospitals based on geography, with the basic principle being that the hub hospital should be the one closest to a spoke that was capable of performing primary PCI or providing pharmacoinvasive therapy. Of the four hubs, three had the capability to perform emergency coronary angiography and 24-hour PCI. One could provide PCI but only between 8 AM and 4 PM daily.

“The protocol followed by EMS was that once STEMI was confirmed, the patient was transferred to the closest STEMI hospital within the cluster, bypassing other hospitals,” Alexander said. “This could be a hub (for primary PCI), or a spoke (for thrombolysis and subsequent transfer within 3-24 hours to a hub).”

Compared with the year prior to implementation of the system, increases were seen in the use of angiography (60.8% vs 35.0%; P < 0.001), as well as PCI (46.5% vs 29.5%; P < 0.001). The increases were most dramatic at spoke hospitals, where angiography increased from 3.5% to 31.3% and PCI from 3.1% to 20.6% (both P < 0.001). Overall reperfusion use and times to reperfusion were similar before and after implementation of the hub and spoke model, as was in-hospital mortality.

Rates of primary PCI also were higher after than before the system was in place (40.7% vs 21.8%; P < 0.001), and mortality was lower at 1 year (17.6% vs 14.2%; P = 0.04). The researchers also documented increases in prescriptions written for aspirin, statins, and dual antiplatelet therapy.

In an email, Alexander said the most striking change in practice was observed among patients presenting to the spokes in distant rural areas. He explained that the standard treatment in these centers prior to implementation of the model was standalone thrombolysis, which decreased from 77.1% to 46.3%. He credited a conversion to pharmacoinvasive therapy as the main reason for the reduction in mortality at 1 year.

Upping Patient Confidence and Maintaining the System Still Challenging

While the system clearly worked and patients benefited from its implementation, Alexander said, linking the program with the state government insurance for Below Poverty Level (BPL) individuals living in the Tamil Nadu region ensured that the predominantly rural poor who lived there could access invasive treatment. Expanding the concept to other states in India, he added, likely will require a fair amount of lobbying with individual state governments.

But setting up the system is not enough, as the researchers quickly learned. Convincing patients in countries with poor access to healthcare that equitable treatment is available to them may be one of the biggest hurdles for this project and others like it. Alexander related one case in which a daily wage earner from an impoverished rural area developed an anterior wall STEMI and presented to a spoke hospital. After thrombolysis with streptokinase his pain persisted with no significant ST resolution. Arrangements were made to transport him to the hub hospital for rescue PCI. However the patient and his relatives flatly refused the transfer, convinced that they would be made to pay a fortune for any treatment there.

“All efforts by the local doctors at the spoke to explain to them that the transport and treatment would be paid using the BPL insurance failed to convince them,” Alexander observed, adding that one of the most common causes of rural indebtedness in India is borrowing money for healthcare. “The patient had obviously heard about treatment costs in these corporate tertiary care centers being prohibitively expensive,” he said. “[He] continued treatment in the spoke and eventually died on the third day.”

Keeping the TN-STEMI model up and running is another challenge, since unlike the Western system of STEMI management, it is a more structured process that requires an implementing agency to ensure that devices work, data collection is in real time, regular training of medical personnel continues, and audit and quality improvement measures are continuous, Alexander explained. Given this situation, private-public partnerships with each state government will be necessary to expand the concept throughout India.

While Alexander and his colleagues believe that their model can be adopted by other middle- and low-income countries facing similar issues, they say an important concept—and one that defies most Western thinking—is that “focusing on primary PCI as the exclusive mode of reperfusion is not feasible.”

Similarly, in an editorial accompanying the study, Amitava Banerjee, MBBCh, MPH (University College London, England), notes that multiple issues remain to be addressed before the model could be adapted across India and elsewhere.

“Tamil Nadu, like Kerala, is not representative of all states in India and is at the relatively higher end of the spectrum in terms of health, wealth, and development; therefore, the results may not be transferable to other parts of India,” Banerjee observes.

To TCTMD, Alexander said that assessment is fair. “We will have to start with similar states,” he said. “Also, there should be a statewide ambulance service (currently available in 16 states) and a BPL insurance program in place. We feel that gradually other states will also try to match up.”

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Alexander T, Mullasari AS, Joseph G, et al. A system of care for patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction in India: The Tamil Nadu–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Program. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Banerjee A. Quality improvement in cardiac services in India: quo vadis? JAMA Cardiol. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Alexander and Banerjee report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments