Largest Study of VITT After COVID-19 Vaccination Digs Into Lab, Clinical Features

This complication is “quite rare but potentially catastrophic,” Chip Lavie says. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are needed.

A look at the largest cohort yet available of patients with vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) after receipt of the adenoviral-vector COVID-19 vaccine from Oxford/AstraZeneca confirms that the condition mostly affects younger adults and typically arises 5 to 30 days after the first dose.

Indeed, 85% of examined cases from the United Kingdom involved people younger than 60, and more than half (56%) involved those younger than 50, even though the UK vaccination program initially focused on older adults, according to researchers led by Sue Pavord, MBChB (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England).

Overall mortality was high (22%), with even greater risks “among patients who presented with severe thrombocytopenia, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [CVST], intracranial hemorrhage, laboratory markers of severe coagulation activation, or all these variables,” they report in a study published online August 11, 2021, ahead of print in the New England Journal of Medicine. Patients with platelet counts below 30,000 per mm3 and intracranial hemorrhage were most likely to die, with a mortality rate of 73%.

Fortunately, the complication appears to be rare, with an estimated incidence after a first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine of one per 100,000 people 50 and older and one per 50,000 in younger adults. This is consistent with prior reports, including those related to another adenovirus-based vaccine (the Janssen shot from Johnson & Johnson).

To TCTMD, Pavord said the message for the public regarding the safety of vaccination is to “absolutely follow your country’s national policy. Each country’s risk and benefit analysis will be different, because it depends on the status of the pandemic during that time.” The UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, for instance, has recommended that people younger than 40 receive a vaccine other than the one from Oxford/AstraZeneca, which at this point would be the shot from Pfizer/BioNTech. Those considerations are likely to change over time as the pandemic waxes and wanes, she noted. “It’s not a static risk-benefit balance.”

Pavord highlighted the massive toll of COVID-19 itself and the effectiveness of the vaccines at preventing deaths. But “everything comes with a price,” she added, “and that’s why it is so important after the [Oxford/AstraZeneca] vaccine, or after any vaccine, to be looking out for unusual symptoms that occur 5 or more days [later],” such as unusual headaches, abdominal pain, and blurred vision. When those occur, people should seek urgent medical attention, she advised.

For Carl “Chip” Lavie, MD (John Ochsner Heart & Vascular Institute, New Orleans, LA), whose group this week published a review on the clinical features and management of VITT accompanied by CVST, “the benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks.”

He underscored in emailed comments to TCTMD that “this is a quite rare but potentially catastrophic reaction to the COVID-19 vaccines, especially the adenoviral-vector ones. Mortality is high, so early diagnosis and aggressive treatment is needed.”

First UK Cases

Because of the early vaccine rollout in the UK, with the program starting January 4, 2021, the country was the first to start seeing cases of VITT, a condition with similarities to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), beginning in March. Reports from other countries subsequently started coming in. “We had the opportunity really to consider carefully the definition,” Pavord said. “And I think that’s very important because some of the publications have misinterpreted the syndrome or mixed it up with other thrombotic problems related to the vaccine rather than [focusing on] this very specific syndrome of VITT, which is immune-related.”

Pavord and others put together an expert hematology panel to systematically study the issue and develop management recommendations. As part of that effort, they prospectively collected data from centers around the UK and gathered retrospective data on patients with suspected VITT who presented before the condition was recognized. The current analysis includes 220 patients with definite or probable VITT treated between March 22 and June 6, 2021.

VITT was carefully defined using five criteria:

- Onset of symptoms 5 to 30 days after vaccination

- Presence of thrombosis

- Presence of thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 150,000 per mm3)

- D-dimer greater than 4,000 fibrinogen-equivalent units

- Presence of antibodies to platelet factor 4

Overall, 170 patients had definite VITT (all five criteria met) and 50 had probable VITT (one criterion was not met, usually because of missing data). All of these patients had received a first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine and presented 5 to 48 days (median 14) after the shot. Median age was 48 (ranging from 18 to 79), and there was no strong disparity by sex (55% of cases were in women). Moreover, there were “no identifiable medical risk factors,” the researchers report.

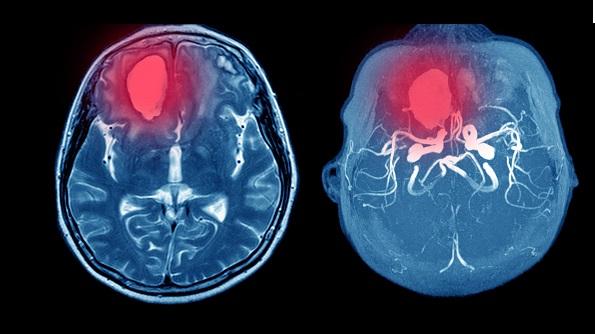

The condition most commonly affected the cerebral veins (in half of patients); 36% of those in this group had CVST complicated by secondary intracranial hemorrhage. The deep veins of the legs and pulmonary arteries also were frequently involved (in 37% of cases), and 29% of patients had multiple vascular beds affected.

“What’s most noteworthy is this massive activation of the coagulation system,” Pavord said. “Neuroradiologists have described clot re-forming as they’re pulling it out from a thrombectomy. It’s so aggressive. It’s very different from normal thrombosis that we see. It just keeps propelling itself and developing, and so until people have had treatment that cuts off the coagulation activation, they are at risk of it developing further and further. So it’s very aggressive, and that’s unusual. That’s not something we’ve seen before.”

Tailoring the Therapeutic Approach

From the detailed analysis of cases, “we’ve been able to tailor make our management guidelines,” Pavord said, noting that their guidance has been available on the British Society for Haematology website since March and has informed the approaches taken by other countries.

“I think we’re all singing from the same hymn sheet, and first-line treatment is intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], which raises the platelet count by stopping or containing the immune response—so hopefully reducing anti-platelet factor 4 antibodies as well as helping to prevent platelet activation,” she said. At the same time, anticoagulation is given to prevent the development of further thrombosis.

In this study, IVIG was used in 72% of patients on the first day of admission, with 11% receiving a second dose for ongoing or relapsed disease.

The vast majority of patients (91%) received anticoagulation—that includes nonheparin drugs in 68% and heparin in 23%. Though some researchers have recommended against using heparin in this setting because of the similarities between VITT and HIT, mortality was similar in those who received heparin and those who did not (20% vs 16%).

Seventeen patients who had severe disease involving CVST, thrombosis at multiple sites, or both underwent plasma exchange. Fully 90% survived, “considerably better than would be predicted given the baseline characteristics,” Pavord et al write.

Other treatments included systemic glucocorticoids in 26% of patients (including half of those with platelet counts below 30,000 per mm3) and neurosurgery or thrombectomy in 15% of patients with extensive CVST.

These findings generally fit with Lavie’s recommendations for treatment of VITT with or without CVST, which involve “early diagnosis; anticoagulation with nonheparin anticoagulants; IVIG, possibly in combination with steroids; avoiding aspirin; and consideration for early plasma exchange in sicker patients. Only use platelet infusions when serious bleeding is present or high-risk procedures are required.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Pavord S, Scully M, Hunt BJ, et al. Clinical features of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

- Pavord reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments