New Surgical Valve Durability Data Set ‘Critical Benchmark’ for TAVR Devices

As transcatheter approaches move to younger, lower-risk patients, operators will have to weigh the risks and benefits. Better durability data will help.

Only about 35% of patients receiving surgical aortic valve replacement with bioprosthetic devices survive to 10 years, and close to one-third of the surviving population exhibit subclinical structural valve degeneration, according to new data.

“Valve durability will be one of the most important issues in the next few years, especially during the TAVR era,” senior study author Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, Canada), reminded TCTMD. “TAVR is already showing similar if not better acute results compared to surgery, but then we'll need to demonstrate that the technique and the valves especially can mimic the durability that has been shown with surgical valves.”

The motivation for the study was “to provide really contemporary data in a nonbiased cohort” in order to understand the benchmark set by surgery, Rodés-Cabau noted. Prior studies have typically included specific valve types and nonconsecutively treated patients.

Michael Reardon, MD (Houston Methodist Hospital, TX), who was not involved in the research, agreed. “This is a really good study with 100% follow-up that is now very carefully looking at the gradations of structural valve deterioration, which will help us as we start comparing TAVR valves,” he said. These data “will be a good yardstick for us to use against” forthcoming long-term results from the two intermediate-risk TAVR trials that are following patients through 10 years.

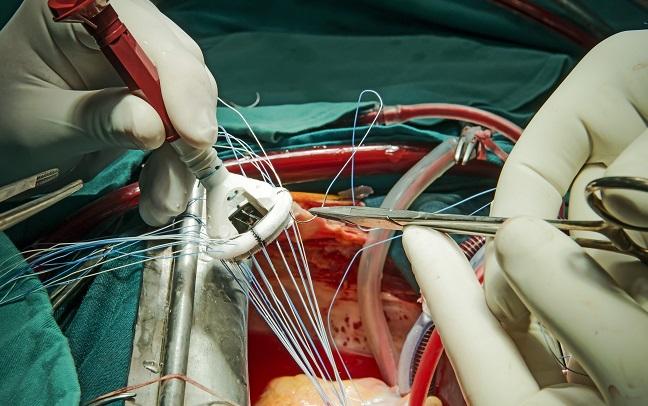

For the study, published in the April 3, 2018, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Rodés-Cabau along with first author Tania Rodriguez-Gabella, MD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute), and colleagues looked at 672 consecutive patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement at their institution between 2002 and 2004 with one of the following bioprostheses:

- Mosaic (Medtronic): 34.8%

- CE-Pericardial Magna (Edwards Lifesciences): 34.2%

- CE-Perimount (Edwards Lifesciences): 16.1%

- Freestyle (Medtronic): 7.7%

- Mitroflow (LivaNova): 7.1%

At a median follow-up of 10 years, 64.3% of patients had died, including 22.5% from cardiovascular causes. Older age, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, higher body mass index (BMI), A-fib, and baseline LV dysfunction were associated with an increased risk of all-cause death. Older age, previous CABG, diabetes, previous stroke, and higher BMI were linked with increased cardiovascular death.

Transthoracic echocardiographic data at 10 years showed a mild but significant increase in mean transprosthetic gradient (6.6 mm Hg; P < 0.001) and a mean decrease in effective orifice area (EOA; 0.3 cm2; P < 0.001) compared with results seen immediately after surgery.

Among surviving patients, 6.6% developed clinically relevant structural valve degeneration (mean transvalvular gradient increase of 26 mm Hg and EOA decrease of 0.7 cm2) and 82.9% of them underwent reintervention. Additionally, 30.1% of patients alive through 10 years developed subclinical structural valve degeneration (mean transvalvular gradient increase of 14.8 mm Hg and EOA decrease of 0.5 cm2).

On multivariate analysis, older age was associated with subclinical degeneration; increasing BMI and use of the Mitroflow valve were associated with clinically-relevant degeneration. Clinically-relevant degeneration was more common in younger patients under 65 years than in older ones, but subclinical degeneration was more prevalent in patients older than 75 years compared with those under 65.

TAVR Is ‘Refining’ Old Surgical Definitions

Compared with previous research, the results pertaining to clinically-relevant structural valve degeneration are “really good,” Rodés-Cabau said. But given the higher rate of subclinical degeneration, “probably these patients have to be followed more closely,” he added, especially since mortality was “mainly related to older age and noncardiac comorbidities [and not] to the SAVR per se.”

The main purpose of the study was to understand valve durability at this point in time and to use it as the benchmark that needs to be met or surpassed moving forward, Rodés-Cabau said. “When we talk about younger patients in the TAVR field or in the SAVR field, and in the low-risk studies, life expectancy will be much longer. Nowadays in the TAVR field, the vast majority of these patients have died at 10 years for sure, but going down with age will increase the longevity [needed for the valves] and then we have to be sure that valve durability is as good as the ones we observed here in this article.”

Reardon agreed. “TAVR has caused us to start to look at what we think of as structural valve deterioration in a different way and a more refined way,” he said. “The old surgical way was either your valve was okay or you had structural valve deterioration. Either on or off. It didn't even count as ‘on’ until it was really bad. What these investigators are saying is there's a slow gradation as you develop this, and we're going to define that.”

In an accompanying editorial, Paul Fedak, MD, PhD (Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta, Canada), Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), and Subodh Verma, MD, PhD (St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada), write that structural valve degeneration is the “sine qua non of the disease inherent to a bioprostheses and the Achilles’ heel for its use in patients with aortic valve disease, especially when they are on the younger end of the age spectrum.”

What this study suggests is that “a contemporary bioprostheses is indeed a benign disease with excellent long-term durability,” they add. “As such, this study will serve as a critical benchmark for SAVR using a contemporary bioprostheses.”

But for younger patients, these results should temper the “clinical momentum” for primary TAVR, the editorialists write, especially since other studies have shown a survival benefit for implanting mechanical valves in these patients. “Both patients and resource-challenged healthcare systems can benefit from the ‘one and done’ approach offered by a mechanical solution,” they say.

For surgeons who are reluctant to send lower-risk patients for TAVR because of a lack of durability data, Reardon said that is a “cop-out.” He said he asks these surgeons what surgical valve they like to use. “They'll tell me something like, ‘Well, I use the Trifecta valve.’’ And I go, ‘We don't have 10-year data on Trifecta. It hasn't been out that long.’”

Future studies of aortic bioprostheses, no matter the type, should be “vigilant and more rigorous,” according to the editorialists. “In this era of rapid innovation, expertise-based randomized clinical trials may help facilitate improved evidence-based decisions for aortic valve interventions. The devil you know is better than the devil you do not.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Rodriguez-Gabella T, Voisine P, Dagenais F, et al. Long-term outcomes following surgical aortic bioprostheses implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1401-1412.

Fedak PWM, Bhatt DL, Verma S. Aortic valve replacement in an era of rapid innovation: better the devil you know. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1413-1416.

Disclosures

- Rodés-Cabau reports holding the Canadian Research Chair “Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière” for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions.

- Rodriguez-Gabella reports receiving support by a grant from the Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero, Madrid, Spain.

- Reardon reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Fedak reports receiving honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly.

- Bhatt reports serving on multiple advisory boards and receiving research funding and royalties from several drug and device manufacturers.

- Verma reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Valeant, LivaNova, and Abbott.

Comments