No CV Safety Differences for COX-2 Inhibitor vs Other NSAIDs in PRECISION

NEW ORLEANS, LA—Ten years in the making, with more than two out of three patients dropping out of the study, the PRECISION trial has found that the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib is as safe—from a cardiovascular standpoint—as two of the world’s most popular anti-inflammatory drugs, ibuprofen and naproxen.

Risk of gastrointestinal events, however, was significantly lower with celecoxib than with either of the two older nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Renal events were also lower in the celecoxib group as compared with the ibuprofen group and the naproxen group, but the difference was only significant in the celecoxib/ibuprofen comparison.

“These findings challenge the widely held view that naproxen provides superior cardiovascular safety,” Steven Nissen, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), said during the late-breaking clinical trial session where he unveiled the long-awaited results at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2016. “These findings,” he continued, “will require careful review by global health authorities to determine what changes in labeling or regulatory status of these drugs are warranted.

A Long-Running Saga

The COX-2 inhibitor saga dates back to the late 1990s, when the approval of another agent from the same class, rofecoxib (Vioxx; Merck), led swiftly to blockbuster sales surpassing $2 billion per year. Five and a half years later, however, Merck withdrew the drug due to an excess of myocardial infarction and stroke among people taking the drug and facing widespread criticism for having failed to act sooner to protect patients from risk.

Celecoxib, which received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2001 and lost patent protection in 2014, was allowed to remain on the market but on the condition that its manufacturer, Pfizer, conduct a cardiovascular safety trial. The results were presented today and also published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“After the withdrawal of rofecoxib, everybody thought they knew the answer, that COX-2 [inhibitors] had an unfavorable cardiovascular profile,” Nissen said, presenting the data to the media. “We didn’t find that, and this is the type of study that once again teaches us that if we jump to conclusions based on mechanistic considerations we often make very bad decisions. We have to get these trial done. We recognize that this trial, like all trials, is not perfect, but it certainly does not show an excess of cardiovascular events with celecoxib.”

Key Results

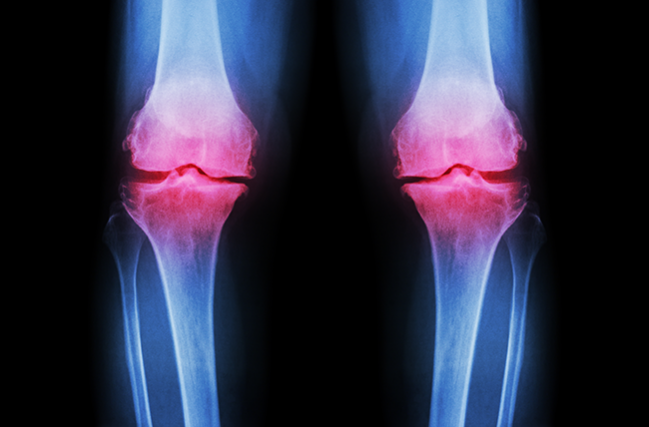

PRECISION enrolled adults requiring daily NSAID treatment for arthritis that could not be managed with acetaminophen, permitting some uptitration of all three drugs during the trial, although the higher 200-mg dose of celecoxib was only permitted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, not those with osteoarthritis who made up roughly 90% of the study population. In all, the study enrolled 24,081 patients with arthritis who also had established cardiovascular disease or were deemed to be at increased cardiovascular risk. Almost 1,000 centers in 13 countries participated in the trial, randomizing patients equally to one of the three treatments.

As Nissen showed here, a full 68.8% of patients dropped out during the 10-year trial, which mandated a minimum follow-up of 18 months: 27.4% of patients discontinued their follow-up appointments, 2.5% died, roughly 15% withdrew consent, and 7.2% were lost to follow-up before their final visit.

After a mean treatment duration of 20 months in all three groups, a primary outcome event—cardiovascular death (including hemorrhagic death), nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke—had occurred in 2.3% of celecoxib-treated patients, 2.5% of the naproxen-treated patients, and 2.7% of the ibuprofen group in the intention-to-treat analysis. Differences between groups were not statistically significant and met the definition of noninferiority when celecoxib was compared with either of the two NSAIDs. No significant differences emerged for any of the components of the composite endpoint, nor from a range of additional secondary endpoints with the exception of serious gastrointestinal events, which were significantly lower in the COX-2 inhibitor group as compared with the two NSAIDs individually. Renal events and hospitalizations for hypertension were both significantly lower for celecoxib versus ibuprofen (but not versus naproxen).

Of note, naproxen showed a small but significantly increased benefit in terms of pain relief over the other two agents.

Dropouts in the study reflect the “challenges of long-term treatment of a painful condition in patients who frequently experience frustration with unrelieved symptoms and switch therapies or leave the trial,” the authors note in the paper. However, similar results between the intention-to-treat and as-treated populations in the study “suggest that low adherence was unlikely to have influenced the principal conclusions, [although] the high levels of nonretention make interpretation of the findings challenging.”

No Safe NSAID for High-Risk Patients

During the press conference, Elliot Antman, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), the trial’s designated discussant, pointed to a number of problems with the study, some of which Nissen himself had also acknowledged to the press.

For one, said Antman, it will be important to look at what dose of study drug patients were taking at the time of their events, whether they were also taking a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)—prescribed in all three groups—and whether they were also taking aspirin. Nearly half of patients in PRECISION were listed as having prior aspirin use, but as Antman stressed to the press, whether or not a patient was taking aspirin at the time of a cardiovascular event or a gastrointestinal bleed will have an important bearing on how these results are interpreted.

Antman also pointed out that while the trial was intended as a study of NSAIDs in patients at high cardiovascular risk, this was not ultimately who the trial involved. “Eighty percent patients here were receiving primary prevention so we don’t know if they had heart disease, and they [were at] lower risk than originally anticipated,” he said.

Both the American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines state that NSAIDs should be avoided in patients at high cardiovascular risk and that remains true, Antman concluded. As such, “we should . . . avoid NSAIDs in patients with known heart disease and if one must treat a patient with an NSAID, try to identify the lowest-risk patient and use the lowest-risk drug in the lowest dose needed for the shortest period of time.” And going forward, he added, focused studies that tailor medications to an individual patient’s genetic risk need to be done to understand the safety of existing NSAIDs. Moreover, Antman stressed, “there is an urgent clinical need for novel analgesics and other therapeutics to avoid the CV risk from all NSAIDs.”

Milton Packer, speaking during the press conference, put it even more bluntly: “No one should walk away thinking that COX-2 inhibition in patients with cardiovascular risk is a safe thing.”

The trial received tepid praise in a Circulation viewpoint released to coincide with the main results today. “The headline results are striking: no difference in the cardiovascular hazard from the three NSAIDs; no evidence supportive of an aspirin-NSAID interaction; and no evidence to suggest that naproxen is safer than the other two drugs,” Garret A. FitzGerald, MD (University of Philadelphia, PA) writes, adding, “Fewer serious GI events and renal adverse events were also noted on celecoxib‐treated subjects. Given that this was a randomized trial in ~24,000 patients, has PRECISION delivered a precise outcome and should it alter practice? Unfortunately, the answer is no.”

FitzGerald goes on to list many of the same concerns as Antman, also noting that of the roughly 8,000 patient in each arm of the study, 5,000 had stopped their assigned therapy by the time the trial wrapped up and 30% were lost to follow-up. “All of these observations intersect . . . to question the validity of the conclusions around noninferiority,” he says. “In summary, there are so many problems with the interpretation of PRECISION that it fails to inform clinical practice.”

Responding to Criticism

Asked during the press conference whether PRECISION had ultimately studied “the wrong population,” Nissen shrugged and said, “It’s the patients we were able to study.”

To be enrolled in PRECISION, patients had to have osteo- or rheumatoid arthritis and be NSAID dependent. “If we had also required you to have existing heart disease, the trial would still be going on. It took 10 years to find enough of these patients so we had to make some compromises,” Nissen said. About 20-25% of these patients had existing heart disease and 35% had diabetes, he noted.

On the dose-efficacy question, Nissen pointed out that both naproxen and ibuprofen were actually taken at doses below the maximum allowable dose. “We used [all of] these drugs as they are used now in the community, we got equivalent analgesic efficacy, and that is the most compelling evidence I can give you that these drugs were used as intended,” he commented. “Even if you could argue that there was a tad higher level of dosing with ibuprofen and naproxen, it still doesn’t change the primary outcome here. . . . The noniferiority conclusion here is rock solid.”

To TCTMD, Nissen confirmed that analyses based on dosing levels, concomitant aspirin, and PPI use are planned. But he refused to be drawn out on the question of what physicians can now tell their confused patients.

“This is the toughest question of all, and I’m going to be very interested to hear what the FDA says,” he told TCTMD. “The problem is, we cannot allow people to suffer from pain.”

PRECISION was trying to test the hypothesis that a second COX-2 inhibitor had the same harmful CV effects as rofecoxib, “and we couldn’t confirm that,” he continued. “Everyone is going to have to decide for themselves [what drug to take]. My job here is to as neutrally as I can is show people what we did with all of [the trial] limitations and be transparent. Look: this was an incredibly hard study to do, these people are chronically in pain, they hurt, and we did everything we could to keep them as randomized.”

As to the renal concern, Nissen acknowledged that nephrotoxicity is a known side effect of NSAIDs but said he was “completely surprised” by the excess toxicity seen with ibuprofen despite the drug not showing superior pain relief.

On a signal of higher all-cause mortality seen with naproxen that narrowly missed statistical significance in the intention-to-treat analysis but was statistically significant in an as-treated analysis, Nissen called the finding “borderline” and “hypothesis generating.”

“The whole controversy [with COX-2 inhibitors] occurred because people didn’t put everything on the table with Vioxx, so we’re putting it on the table,” he told TCTMD. “The original VIGOR manuscript concealed the differences between rofecoxib and naproxen. I would also point out to you that rofecoxib was worse than naproxen and a lot worse—we didn’t see that here.”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;Epub ahead of print.

FitzGerald GA. ImPRECISION: Limitations to interpretation of a large randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2016;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Pfizer sponsored the trial.

- Nissen reports consulting for “many pharmaceutical companies” but that honoraria, speaking or consulting fees are paid “directly to charity so that neither income nor tax deduction is received.”

- FitzGerald reports having served as a consultant for Pfizer.

Comments