Off Script: After ISCHEMIA, the Devil Is in the (Design) Details

This blog was adapted for TCTMD from a 40-point “tweetorial” first posted on Twitter.

A key lesson one can learn from experience in designing clinical trials is that the devil is often in the details. Trial design is equally as important as—if not more important than—trial execution. There are many trials that are “won” or “lost” in the design phase alone, BEFORE the trial is even underway. A critical area to which this applies is in the selection and definition of trial endpoints. It might seem intuitive that a “heart attack” or myocardial infarction (MI) is easily recognized clinically. But if one goes deeper, there is far more that goes into objectively defining an MI than first meets the eye. Remember, for high quality trials, an independent clinical events committee reviews patient charts and tries to make a determination about whether patients have had MI events based upon the definitions that are pre-specified within the trial protocol.

In reviewing the recent ISCHEMIA and EXCEL trials, this specific issue of how MI’s were defined (especially after procedures) became very relevant, and I thought it might be interesting to tweet (and write) about it. The below is adapted from the “tweetorial” I posted last week.

First: a little primer on periprocedural MI. This is relevant because there has been a fair amount of discussion on it after the ISCHEMIA trial results were presented. I thought it might be worthwhile to share some past knowledge here in case you weren’t around for it. Let’s start with a poll I posted on Twitter, then go backwards in time because history lessons are more fun that way. I asked Twitter (and 439 tweeps responded): In routine clinical practice—to distinguish from research studies—do you draw cardiac biomarkers after PCI in your cath lab?

- No more (I stopped years ago): 70%

- No more (I stopped recently): 13%

- Yes: 18%

This poll was no doubt slightly skewed by those who are very smart/know what I’m getting at and they likely tried to rig the poll to say “yes” to undermine me. But I will tell you that most labs have abandoned the measurement of cardiac biomarkers post PCI. Why?

Hint: it’s not that interventional cardiologists have our heads in the sand and don’t want to know about periprocedural MIs, although that might seem the most obvious answer. In fact, there was actually a time when the routine measurement of periprocedural biomarkers was a marker of cath lab quality. Yes, these cavemen (as we have often been described) actually have detailed quality standards, published in 2016 and endorsed by multiple interventional societies. These documents are updated regularly so one can check to see when routine biomarker assessments were recommended.

So, pop quiz: when was the last time it was recommended to routinely check cardiac biomarkers following PCI, according to SCAI consensus documents?

7/POLL: When was the last time it was recommended to routinely check cardiac biomarkers following PCI? @SCAI

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

If you guessed the 2016 or 2012 documents, you’d be wrong. The correct answer is 2009, in a document that discusses biomarker assessments. This 10-year-old document was the first to note the fact that PCI, and especially elective PCI, started to increasingly become an ambulatory procedure, meaning that patients could go home the same day as their procedures. In other words, before biomarkers can practically be ascertained. Exceptions in the document include PCI with procedural complications. The bottom line is that routine measurement of biomarkers post-elective PCI hasn’t been recommended in a long time.

The next question is, why?

10/So the bottom line is that ROUTINE measurement of enzymes post-elective PCI hasn’t been recommended in a long time.

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

But why is that?

You could argue that that there are two correct answers here, #3: "cost containment" and #4: "no clinical consequences". But because #3 is so obvious, I’m hoping that I shocked you a little bit with #4. Wait . . . elevated cardiac biomarkers after PCI are of no clinical consequence? How can that be? It turns out that this has been extensively studied. This Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) paper by Allen Jeremias and colleagues in 2004 showed that post-PCI biomarker elevations, even those eight times the upper limit by CK-MB, only had a relationship to mortality if they were associated with unsuccessful PCI. Note also the overall rates of MI in this study: CK-MB elevations were found in > 10% of successful procedures. There are many other studies that describe the fact that cardiac biomarker elevations post-PCI (without other angiographic/clinical signals) have virtually no consequence and may only be a marker of disease. This is even more relevant with more-sensitive troponin and high-sensitivity troponin assays.

This is why the SCAI consensus document published in 2013 by Issam Moussa and colleagues was written, and it nicely summarizes the literature on postprocedural MI. Note that one of the reasons for this document was because other definitions of MI (for example, the Universal Definition of MI) had come along, relying on more sensitive assays, the prognostic import of which was less clear-cut specifically for post-PCI MI. With these new assays, biomarker elevation could be detected in a large percentage of patients, but harkening back to the original PCI data, these were of such little clinical consequence that we were sending patients home without even collecting these biomarkers. Indeed, this is one of the reasons that some more recent studies, for example EXCEL, used more stringent definitions of periprocedural MI based upon the SCAI definitions above. Larger MI’s were associated with late mortality as depicted in a European Heart Journal publication earlier this year.

19/Here are the actual data for these large MI’s. pic.twitter.com/saMb7tZwHm

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

So why is all of this important?

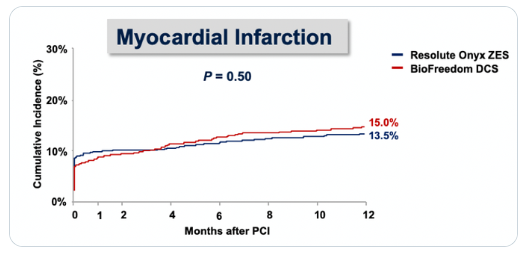

There has been a lot of debate recently specifically looking at the issue of periprocedural MI. The ONYX ONE randomized trial, presented a few months ago at TCT 2019, for example, looked at two stents head-to-head and you’ll note the rates of MI at day zero.

You’re thinking: Wow, that seems like a lot of MI! Is it because we cause clinically consequential MI’s in 10% of patients in a contemporary stent trial? Or what else could explain this? In fact, in the trial, all biomarkers were collected and monitored, the third Universal Definition of MI was used, that is, a troponin five times the 99th percentile, and the population was higher-risk, all-comers (more than 50% had ACS, including STEMI). But in ONYX ONE, these MI’s were likely of little clinical consequence and likely wouldn’t have been measured in clinical practice, outside of a clinical trial.

Skeptics will say, But wait, we know definitions/assays are more sensitive nowadays, so why is this any different than a spontaneous MI (AKA troponin leak) with a sensitive assay? What do the data show? In fact, this has ALSO been studied. As Prasad et al demonstrated in JACC in 2009, procedural MI actually has less impact upon longer-term outcomes than spontaneous MI.

26/This has ALSO been studied cc:@f2harrell. And procedural MI actually has less impact upon longer-term outcomes than spontaneous MI.

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

Here’s a paper from #ISCHEMIA co-PI @greggwstone @jaccjournals Top (B) is for NSTEMI, Bottom (C) is for unstable angina. pic.twitter.com/1HcefJjZfL

Another paper from ISCHEMIA-CKD principal investigator Sripal Bangalore in the American Heart Journal has also looked at this in 7,000 patients undergoing PCI in the EVENT registry, stratifying outcomes by MI subtype.

Now, while MI definitions can vary, these data do suggest that it is the occurrence of spontaneous MI that has the strongest association with mortality, and more specifically, CV mortality. Notably, both of the studies cited above required routine biomarker assessments post-PCI.

So what is the point of all of this?

Clinical trial interpretation requires an understanding of the different vagaries of trial design (for example, routine biomarker collection) and what is actually relevant to clinical practice. Any study result, and that includes ISCHEMIA, EXCEL, and others, for which the result is partly driven by differences in procedural biomarkers, should be carefully examined to determine whether these periprocedural versus spontaneous MIs were associated with other adverse outcomes, especially CV deaths and even HF rehospitalizations.

So what would have happened to primary and secondary endpoints, for example, if even more sensitive, periprocedural MI definitions were used in ISCHEMIA? Remember all events are reviewed/adjudicated but the adjudicators had to use prespecified definitions. If a MORE sensitive procedural MI definition had been used, the invasive strategy would have looked awful. The current headlines would have been even more misleading, suggesting perhaps that an invasive strategy actually CAUSES many MIs, affecting both the early and total numbers. But would that actually be any more relevant to patients? Moreover, if we did that, would we also be wrong to discount the larger MI’s detected by the routine assessment of biomarkers in ISCHEMIA that have been previously shown to have clinical importance?

Shocker: in current day cardiology practice, a good proportion of the procedural MI’s that were detected in ISCHEMIA would never have been measured in the first place, but the spontaneous ones would all have been caught, because they were drawn for clinical reasons. And if that were the case, just imagine what the ISCHEMIA curves for the “holy grail” CV/death endpoint would have looked like, if driven by lower rates of spontaneous MI, but also numerically lower late CV deaths? Not only would have ISCHEMIA shown better quality of life with an invasive strategy, but it could also have shown reduced MI, reduced CV death/MI, and a reduction in the five-component composite endpoint. On the other hand, if we didn’t detect any of these biomarker elevations, we would also be downplaying the larger MIs detected by the routine assessment of biomarkers in ISCHEMIA that have been previously shown to have clinical importance.

34/And if that were the case, just imagine what these #ISCHEMIA curves (for the “holy grail” CV/death endpoint which was driven by lower spontaneous MI, but ALSO numerically lower late CV death) would have looked like. pic.twitter.com/AgeDS8IxHb

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

Of course, this is all speculation. The SCAI document referenced above does have a recommended clinically relevant MI definition, which is close to the ISCHEMIA definition. The performance of this definition will be tested within the trial itself. One open question is whether we should actively look for these large infarctions with routine biomarker assessment, or whether they always occur in the presence of angiographic/clinical complications. Clinically, to me, the latter seems more likely to be the case.

Because it is all speculation at present, I have gone on the record stating that the "best" headline for the ISCHEMIA trial should read something like: “Landmark study demonstrates safety of deferring invasive approach in selected patients with stable ischemic heart disease.” The proof, however, will be in longer-term follow-up, as well as in testing the relative importance of procedural versus spontaneous MI as adjudicated within the trial. That is why the CV death/all-cause mortality data are also important—albeit underpowered.

41/END Bottom line: I’ve seen enough trials completely reverse outcomes over time (e.g. SHOCK, STICH) to withhold final judgment at this point. The difference though is those were pure mortality outcomes.

— Ajay Kirtane MD SM (@ajaykirtane) November 19, 2019

Thanks for listening; hope it was helpful. pic.twitter.com/KpJepE63qv

Ajay Kirtane, MD, SM, is Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) and Director of the Cardiac…

Read Full Bio

Comments