Should Conduction-System Pacing Be Top Choice for CRT?

In an EHRA debate, experts grappled with how to interpret promising preliminary data while longer-term trials are ongoing.

BERLIN, Germany—Conduction-system pacing (CSP), including His-bundle and left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP), has emerged as an alternative to biventricular pacing for patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), but whether it’s ready to take over as the first-line option remains a matter of debate.

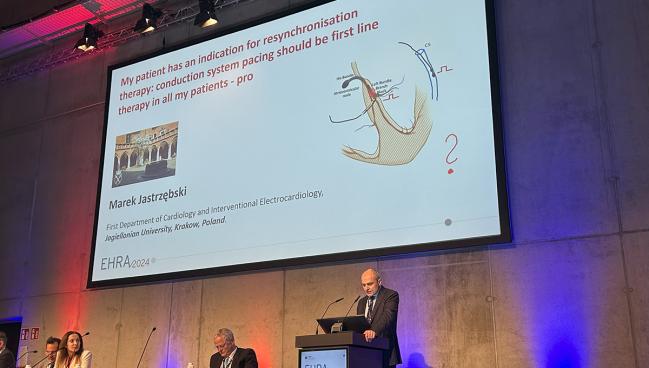

Two experts tackled the question at the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Congress 2024 last week, with Marek Jastrzębski, MD, PhD (Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland), arguing that despite an evidence base that lacks large randomized clinical trials with long-term follow-up, CSP makes sense from a physiological point of view and has compared well against biventricular pacing in observational studies and small trials.

Michael Glikson, MD (Shaare Zedek Medical Center and Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel), on the other hand, pointed to data from numerous randomized trials—with several showing a survival benefit over the long term—in support of biventricular pacing and indicated that the field should wait for the results of multiple ongoing trials before recommending greater use of CSP.

CSP as the First-line Option in CRT

Jastrzębski started his support of CSP as the better pacing option by saying: “When you think about it from the intuitive and physiological point of view, it seems simple because resynchronization therapy is a therapy to correct asynchrony produced by left bundle branch block.”

He argued that CSP is better because it uses the heart’s natural systems. “We pace [the] conduction system using the pathway that was designed to provide synchronous activation and we cure the left bundle branch block simply by pacing behind the level of the block,” Jastrzębski explained. “It seems simple, it seems intuitive, it seems superior. But the problem is, it’s not in the guidelines.”

He was referring to the 2021 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology on cardiac pacing and CRT, for which Glikson was one of the co-chairs. The guidelines have some discussion of CSP, particularly His-bundle pacing, but biventricular pacing remains the go-to approach in CRT based on randomized data from clinical trials.

Synchrony is good and asynchrony is bad, and when you restore synchrony, you have good outcomes. Marek Jastrzębski

But Jastrzębski said he started to shift toward CSP about 9 years ago based on the results he was seeing in the electrophysiology lab. It all started, he said, when a patient with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and typical left bundle branch block (LBBB) failed classic biventricular pacing three times, with those procedures totaling about 1 hour of fluoroscopy time, before a fourth attempt with His-bundle pacing was successful with just 3 minutes of fluoroscopy time. The good results, he said, have held up through 9 years of follow-up.

This type of bailout procedure wasn’t included in the guidelines at the time, Jastrzębski noted, and in the 2021 document, it’s still listed only as a bailout and not a first-line option.

Since then, he said, there has been a shift toward CSP and away from biventricular pacing, with most patients in his lab undergoing CRT with LBBAP.

“So why not to choose it? Because it’s not in the guidelines? Well, I’m sorry, but I believe more in the data that I see in front of my eyes, in the patient that is on the table,” he said.

Jastrzębski argued, too, that the trials of CRT purported to support biventricular pacing can apply to CSP as well. These were CRT trials and biventricular pacing was just the method available to deliver it at the time, he said. The major finding of the trials “was that synchrony is good and asynchrony is bad, and when you restore synchrony, you have good outcomes,” he said. “And this finding translates also to conduction-system pacing.”

He acknowledged that the evidence base in support of CSP is much smaller than that for biventricular pacing, but noted that there have been several smaller trials—like His-SYNC, His-Alternative, LBBP-RESYNC, HOT-CRT, and others—that provide some reassurance that CSP is working. “That tells us that the previous big trials can be used to support using of conduction-system pacing for resynchronization.”

Future trials of CSP are needed to explore aspects like differences in complications when compared with biventricular pacing, but not to determine whether it should be first-line therapy, Jastrzębski said. “Because we already know that it works, and from physiological point of view, this should be first-line therapy.”

Not So Fast

Glikson, however, disagreed, saying that there is not yet sufficient evidence to support a move toward CSP for all CRT candidates.

Jastrzębski “is a CSP giant,” Glikson said. “However, I suspect that in some way my opponent fell in love . . . with conduction-system pacing, and when love is in the air, you tend to neglect the evidence.”

There have been 11 landmark trials of CRT using biventricular pacing, with some reporting survival benefits over long-term follow-up. And it’s this extensive body of evidence that was used to create the 2021 ESC guidelines on pacing and CRT, he said.

The approach to CSP in that document was “very conservative,” Glikson acknowledged, noting that the authors felt the evidence wasn’t strong enough to go further than they did. The only strong recommendation for CSP was a IIa (level of evidence B) recommendation for His-bundle pacing to be considered as an option after unsuccessful implantation of a coronary sinus lead.

Much research into CSP has accumulated since then, with the field evolving rapidly. “It’s moving quickly maybe even faster than the evidence,” Glikson said.

When love is in the air, you tend to neglect the evidence. Michael Glikson

Summarizing that body of literature, he noted that observational studies with follow-up limited to 1 to 2 years suggest a better clinical and echocardiographic response to CSP than with biventricular pacing. The randomized trials, however, have been relatively small with a short duration of follow-up (mostly 6 to 9 months). They’ve shown roughly similar results with CSP and biventricular pacing, with some indications of an advantage for CSP. Yet, Glikson said, it’s “still hard to compete with the large, large body of evidence [in support] of biventricular pacing.”

Those data are coming, with several randomized trials of CRT for bradycardia indications and for CRT underway, but the results are still several years away.

Jan Steffel, MD (University of Zurich, Switzerland), one of the chairs of the debate session at EHRA, suggested that there is a need to wait for those result before making major changes to practice.

It’s important to have the expertise of Jastrzębski and others to push the field forward, but having evidence to support certain practices is critical as well, he said.

The rapid uptake of CSP in the absence of large outcomes trials reminded Steffel of situations in the past when a practice that seemed so intuitive proved to be ineffective or even harmful when put through the rigors of a clinical trial. He pointed to use of CRT in patients with heart failure and a narrow QRS complex, as tested in the EchoCRT trial.

“It turns out, not only does it not help, it may actually be harmful,” Steffel said. “So I think we need to have both. We need to have passionate people, experts who are very good at what they’re doing, but at the same time we need to have the evidence that this ultimately really also works out in the long term with hard endpoints, and we need to have long enough trials.”

For now, “I think we cannot do anything else but wait for the trials and I would strongly encourage people who are really expert implanters and really expert troubleshooters in these situations to not just simply implant these patients but to include them into the ongoing trials,” Steffel said. “We will have that evidence much faster, and we’ll be able to adapt the guidelines much faster. This is the way that evidence-based medicine works in the 21st century.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioDisclosures

- Jastrzębski reports speaking and consulting fees from Abbott, Biotronik, and Medtronic.

- Glikson reports serving on an advisory board for Medtronic.

Comments