Simple Tech Empowers HF Patients, Boosting Health: EPIC-HF and MyROAD

A pre-visit video and checklist sparked medication changes, while a “talking card” helped keep patients out of the hospital.

Innovative interventions that engage and educate heart failure (HF) patients about their medications and help them sustain healthy lifestyles can play a role in ensuring optimal treatment and less frequent hospital visits, according to two studies presented this week at the virtual American Heart Association 2020 Scientific Sessions.

Presenting the EPIC-HF study, which was simultaneously published in Circulation, Larry A. Allen, MD (University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora), said clinical inertia is responsible for a portion of underuse of guideline-directed medical therapies in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). An active patient, who participates in shared decision-making, can be key to overcoming this.

“Patients need to believe that this is what's good for them, and if we take a paternalistic approach and just prescribe, prescribe, and prescribe and don't bring patients along the way with us, we're not going to get the outcomes that we set out to achieve,” Allen said.

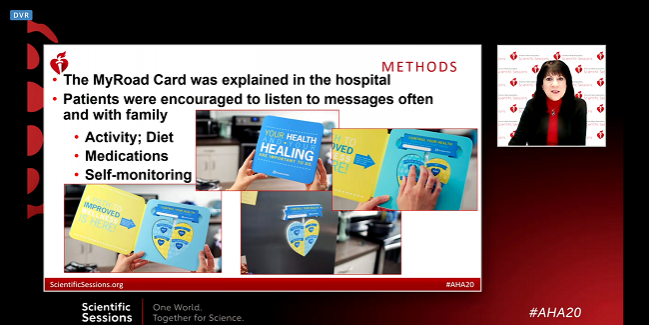

Presenting the 1,000-patient MyROAD study in the same session, Nancy M. Albert, PhD (Cleveland Clinic, Ohio), showed how HF patients recently discharged from the hospital who received an instruction card with recorded audio prompts about physical activity, diet, medications, and self-monitoring had 27% fewer emergency department visits at 30 days and 29% fewer at 45 days than those who did not receive the card at discharge. Patients given cards also were nearly 50% less likely to die from HF at 90 days, and they had less all-cause and HF-related death at 90 days.

EPIC-HF and MyROAD

For EPIC-HF, 290 patients with HFrEF were randomized to either their regularly scheduled checkup or the intervention. The latter consisted of a 3-minute video and a 1-page checklist that directed patients to check off medications they take, fill in the dose, and bring the checklist with them to their appointment. The intervention materials were delivered to patients by email or text in the days prior to the appointment. As a result of the intervention, 49% received intensification of guideline-directed therapy versus 29.7% in the control group (P = 0.001). Additionally, 82% of patients brought the checklist to their appointment, and 73% talked about the checklist with their physician. The majority of patients also said the checklist helped them understand their medical plan and talk about it with their doctor.

Most of the changes that were made among patients who received the video and checklist intervention involved dose up-titrations, according to Allen. Approximately half of patients on beta-blockers, for example, were taking less than 50% of the recommended dose. The majority of all medication changes that occurred as a result of the intervention involved increases in doses of generic drugs that were already being prescribed.

According to Albert, the talking, heart-shaped card given to patients at discharge in MyROAD was designed to be placed in a conspicuous spot in a patient’s home, such as on the refrigerator. When the patient pushes one of the four buttons, it reinforces messages that are typically given at discharge but may be inconsistent depending on who relays them, or may be missed altogether by patients and their family members as they juggle discharge paperwork and get ready to go home. The messages are meant to be replayed often, as reminders.

Erica S. Spatz, MD, MHS (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), the discussant for both studies, pointed out that physicians need their patients as partners, and vice versa. Support tools like the video and checklist, as well as the card, she added, help inform the question of whether technology can improve the ability of HF patients “to manage the work of being a patient and managing their chronic disease.” Encouraging patients to become more educated about their clinical care can benefit both provider and patient, she said.

“We often meet resistance from patients about taking more medication. At a very surface level, oftentimes people tell you, ‘I don't want to take more pills or have a side effect.’ But if you dig a little deeper, what the evidence shows is that most people are reluctant to start any medication, or don't adhere to their medication, because they never really, truly understood the true benefit or value of taking that medicine,” Spatz said.

Long-term Implications

Following his presentation, Allen said healthcare professionals who participated in the study felt that it was a positive experience and, in some cases, said it even saved time by helping them focus the discussion during the scheduled visit.

To TCTMD, he said the next step is to try to understand whether the simple intervention, intended to prepare the patient for one upcoming visit, translates to long-term benefits as a result of improved doctor-patient communication.

If you dig a little deeper, what the evidence shows is that most people are reluctant to start any medication, or don't adhere to their medication, because they never really, truly understood the true benefit. Erica S. Spatz

“It is feasible that this very brief intervention could have significant effects in the way patients consider their medications and take them over time,” Allen commented. “Overall, the premise that patients being more involved in prescribing decisions would lead to greater adherence and use of those medications over time is something that we think is potentially likely, and we will investigate further.”

Spatz said while both intervention types are promising, important questions remain, including whether patients develop greater self-efficacy and experience better quality of life as a result of changes to their disease management, and whether tools designed to help them with their self-care can be “freshened or personalized so that they continue to be relevant for the challenges of managing a chronic disease.”

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Allen L, Venechuk G, McIlvennan C, et al. An electronically delivered, patient-activation tool for intensification of medications for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EPIC-HF trial. Circulation. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Albert NM. MyRoad: My (Recorded On-demand Audio Discharge) instructions. Presented at: AHA 2020. November 17, 2020.

Disclosures

- Allen reports grant funding from the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; and consulting fees from Abbott, ACI Clinical, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, and Novartis.

- Albert reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Spatz reports support from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Comments