Study Finds No Increased Risk of CVD Years After Infertility Therapies

Data are sorely lacking in women’s healthcare, with older studies raising doubts about ART. This study offers some reassurance.

The use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) is not associated with an increased intermediate-term risk of CVD, according to the large multination Nordic ART study.

While some nonsignificant trends were seen depending on the method of ART used, there were no differences in incident CVD risk at a median of 11 years in the overall cohort of women who used ART versus those who did not.

“These findings may be reassuring to the increasing number of individuals who require assistance from ART to conceive,” say Maria C. Magnus, PhD (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo), and colleagues in their paper published online August 9, 2023, in JAMA Cardiology.

Many women with infertility have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or endometriosis, both of which have been linked to a higher risk of CVD, making it important to understand if the technologies themselves contribute further risk, Magnus and colleagues note. Potential ways this could occur are either through ovarian hyperstimulation that results in a prothrombotic state and/or endothelial injury, or by causing accelerated biological aging. Moreover, prior analyses had delivered mixed results as to possible harms of ART.

In an accompanying editorial, Stephanie A. Fisher, MD, MPH (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), and colleagues say the data are much needed and consistent with a 2017 meta-analysis that included over 1.4 million women and found no significant difference in rates of cardiovascular events between those who did and did not undergo fertility treatment, although an earlier large US analysis had pointed to increased risk.

In the same way that we ask people about hormonal contraception or breast or ovarian cancer, we should be asking about infertility treatment. Stephanie A. Fisher

“I think one of the main concerns with the current literature that we have on ART and long-term cardiovascular disease risk is just that we're missing those data,” Fisher told TCTMD. “This dataset is very robust and has one of the longest follow-ups that we have in any cohort to be able to better address this question among people seeking to conceive.”

Nordic ART Population

The study included 2,496,441 individuals who gave birth in Denmark (1994-2014), Finland (1990-2014), Norway (1984-2015), and Sweden (1985-2015). Overall, 4% had received ART. In women with no ART, the mean age was 29 years, while in the ART group it was 33.8 years. In addition to being older, women with ART had a lower parity and were less likely to use tobacco.

Overall, incident rates of any CVD over follow-up that ranged from 5 to 18 years across the studies was not significantly different between those who did and didn’t use any form of ART: 188 vs 152 events per 100,000 person-years (adjusted HR 0.97; 95% CI 0.91-1.02). Similarly, no differences were seen between women in the ART versus no ART groups in rates of ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis. The ART group did, however, show a lower risk of MI compared with the non-ART group (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.65-0.99).

The main findings did not change after adjustment for multiple gestation, pregnancy complications, tobacco use, BMI, or educational level. Individual analyses by type of ART showed a trend for an increased risk of stroke in those who underwent frozen embryo transfers compared with women with no ART (HR 1.59; 95% CI 1.11-2.26), with no evidence of a similar difference between those who underwent fresh embryo transfers and those with no ART (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.80-1.05). The association between frozen embryo transfer and stroke risk persisted after further adjustment for pregnancy complications.

Magnus and colleagues say a heightened risk with frozen transfers “might reflect an increased risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, since preeclampsia is associated with future risk of stroke.” Embryo selection and epigenetic changes associated with freezing or thawing, also could be potential explanations, they add. Importantly, however, it also could reflect a greater severity of female or male fertility problems since having a frozen transfer often occurs after an unsuccessful fresh embryo transfer.

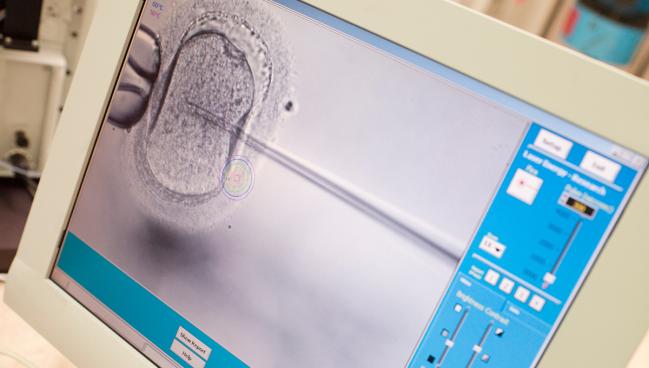

Investigators also saw a significantly lower risk for any CVD with in vitro fertilization (IVF) involving intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) versus no ART (HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.74-0.94). Here, the researchers say their suspicion is that “women who used IVF with ICSI did not have fertility problems themselves, as this reflects largely fertility problems among their partners [and] they might be reproductively healthier, which again might be reflected in their decreased risk of CVD.”

That uncertainty is another ongoing challenge in this type of research, Fisher noted.

“We need to tease out whether it's ART alone or developing hypertension during pregnancy. This study alone is not able to address that, and neither is a lot of our literature,” she said.

The need for long-term follow-up of women who have undergone fertility treatments also raises issues of how or if they are being tracked over time. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative suggest that infertility may be associated with subsequent risk for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, but that many women don’t share infertility history with providers because they either aren’t asked about it or don’t think it’s relevant.

“An egg retrieval should be documented as a surgical procedure as part of the medical history,” Fisher noted. “Getting into the details of ART type is more challenging, but in the same way that we ask people about hormonal contraception or breast or ovarian cancer, we should be asking about infertility treatment [because] it’s an important exposure that we should be capturing in order to better study long-term outcomes.”

While Fisher and colleagues say the generalizability of the Nordic cohort to other more-heterogeneous populations like the United States is somewhat limited, as is the ability to replicate this type of data in a US population.

“We don't have the robust databases like Canada or many of these European countries where they're able to look at hundreds of thousands or even millions of individuals like they did in this study,” Fisher told TCTMD. “I think it's a reflection of the very fractured nature of our healthcare system that we don't have the ability to access these mass reporting systems.”

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Magnus MC, Fraser A, Håberg SE, et al. Maternal risk of cardiovascular disease after use of assisted reproductive technologies. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

Fisher SA, Khan SS, Freaney PM. Assisted reproductive technologies and cardiovascular disease risk in birthing adults—when null results matter. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Magnus and Fisher report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments