The Weight of a Lifetime of Lead: Cardiologists Seek to Ease the Burden

This occupational hazard can lead to painful back and neck injuries that require surgery. Some see new ways forward.

Morton Kern, MD, of VA Long Beach Healthcare System and University of California, Irvine, often engages his colleagues via email in brief, informal dialogue on clinically relevant topics in interventional cardiology. With permission from the participants, TCTMD presents their conversations for the benefit of the cardiology community. Your feedback is welcome—feel free to comment at the bottom of the page.

Morton Kern, MD, of VA Long Beach Healthcare System and University of California, Irvine, often engages his colleagues via email in brief, informal dialogue on clinically relevant topics in interventional cardiology. With permission from the participants, TCTMD presents their conversations for the benefit of the cardiology community. Your feedback is welcome—feel free to comment at the bottom of the page.

Colleagues,

An interventional cardiologist wrote me and asked for advice. Here's the issue:

"I've been in practice for almost 12 years, with the past 10 years being cath lab-only, 5 days a week. Plenty of structural and all the fun stuff. Despite being cognizant of posture, positioning, and all, lead has taken its toll. Three weeks ago, my left hand started going numb intermittently throughout the day. MRI showed normal discs, but C6/C7 bone degeneration is causing nerve exit impingement. I'm doing all the things—NSAID, PO steroids, and soon injection, etc. No weakness but no improvement. I have nothing in my current position to fall back on.

My question—have you seen docs in the lab bounce back from this? Or is it all just how much risk you're willing to take to stay in the lab? Going general is not out of the question, I just didn't think it would be this soon. I'm still working full time and wearing the lightest lead [apron] I have, but you can't always predict when you're going to have a long left radial case and that is really the worst. I have a call in to the Rampart folks [to get a shield system], but best-case scenario we won't have it till next year. Any advice on the matter is appreciated. "

Kern: Sorry to hear of this, but it's probably more common than we know. Not long ago, Kereiakes was temporarily paralyzed from a C6 fracture due to thin bones after years of wearing lead.

I don't know if someone has fully recovered from this kind of injury, but I think it is possible over time without the weight. However, in the short term with symptoms, I'd probably find a way to stop until the lead-free lab has arrived. Call one of the lead-shield companies (eg, Rampart or Protego) and see if they can give you a demo model until the hospital pays the costs.

Alternatively, consider that there may be more money in noninvasive work but much less fun. Ask your partners if there's a way to be covered for some of the left radial cases but that is not a good answer. You never know when a case will go south.

Bonnie Weiner, MD (Saint Vincent Hospital, Worcester, MA):

Alice Jacobs is the other person I know of who has navigated this, ultimately leaving the lab. One of the things that is not always considered when designing the lab is the differing heights of the operators. As one of the shorter individuals in this group, I suspect, when I designed a lab, I made sure not only that the table height came down to a level that was comfortable for me but also that the monitor gantries were mobile enough to come to a level where I could look straight across rather than up. I don’t know if it made any difference except for my comfort, but I have not had back or neck issues. I may have made some of my 6-foot-plus fellows a bit uncomfortable, though.

Peter N. Ver Lee, MD (Northern Light Cardiology, Bangor, ME):

I had a C6/C7 disc herniation when I was 35 (I’m 65 now). My thumb and forefinger were numb, I had triceps weakness. I had a diskectomy and it resolved, but I still have triceps weakness and numbness in the thumb and forefinger. The pain gets better. I have used a Zero-Gravity for about the past 15-20 years. I think it has extended my career. It takes getting used to, but it is definitely worth it. I’d strongly recommend avoiding lead aprons, and with Zero-Gravity, I believe one can make a case for increased physician safety not only from relieving the weight of a lead apron, but from reducing radiation exposure. In the case of a Rampart, it would benefit staff as well. We have portable Zero-Gravity in cath labs, the EP guys have them suspended from the ceiling. Nowadays, I might go with Rampart, even though it’s more expensive than Zero-Gravity.

But yes, you can get back to working in the lab. I’ve done it for 30 years.

Ajay Kirtane, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY):

Sadly this is very common, but the good news is that it usually will improve with the appropriate rest. The inflammation around the affected nerve typically calms down. Epidural injection can be a useful diagnostic test in addition to something that can provide (sometimes transient) relief. While this doesn’t always apply to a situation of bone degeneration, for those with disc herniations, the disc material is often resorbed over time by macrophages, etc, relieving the nerve compression. Because the natural history is typically good for both causes—over a timeline of weeks to months (you must be patient), most can avoid surgery, even with more severe symptoms of pain or even minor weakness.

Whether it is stenosis/impingement/disc herniation, this happens to us, especially for those in the lab continuously. Virtually all of us just “soldier on,” knowing that over time many of us will end up with progression and/or surgery. Core strengthening, especially things like Pilates, can help a lot, but it makes a big difference to not have to wear lead, which is likely the best way to avoid these almost deterministic issues. I personally have barely worn lead over the last 2 years since my microdiscectomy surgery in 2021 for a herniated disc (we got Rampart soon after that).

Timothy D. Henry, MD (The Christ Hospital, Cincinnati, OH):

This is unfortunately far too common, as evidenced by the serial Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) occupational-hazard surveys. There is no excuse for us to not have this solved already, as there are already three radiation systems available (EggNest, Rampart, Protego) that allow the entire room to be LEAD FREE and at the same time cut the radiation we are getting DESPITE lead! I believe it a moral imperative that we are all lead free, and this is a priority for SCAI. There’s lots of recent literature on this; see David Rizik’s editorials! Many on this list are already lead free.

Stephen Ramee, MD (Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, LA):

I agree with our colleagues that this is a serious and common occupational hazard. I know countless interventional cardiologists who have required neck and/or back surgery. I have luckily avoided the same and have long advocated core training like some of you. I recommend the following to my junior colleagues and fellows based on my experience:

1. Do core training to keep your neck, back, and abdomen strong.

2. Make your cases as short as possible.

3. Position the video screens to be at eye level so you are not looking up at them, and directly in front of you so you are not turning your head while working to see them.

4. Obtain disability insurance that specifically covers whether you can be an interventional cardiologist in case of a career-ending injury (spine or otherwise).

5. Seek professional help from a neurosurgeon when you suspect a problem.

I commiserate with and honor all of you who sacrificed your health for your patients. I also applaud those of you who are seeking other solutions to protect our future Interventionists.

Lloyd Klein, MD (UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, CA):

The SCAI surveys we published 5 and 15 years ago showed that cervical hazards were very common, affecting around 30% of respondents. I myself suffered from neck problems. While surgery was never necessary, I did take Celebrex on occasion, and in the last few years, I limited the number of cases per day to two or three because otherwise I would inevitably have pain. I left the lab, in part for this reason, probably 2 or 3 years early, and I have to sleep with my head propped up a bit for periods at night. I think lesser injuries like mine, which never caused an actual loss of time from work, are probably even more frequent. I loved the lab and don’t regret a moment, but this sure is the negative. I am sorry to hear of this interventionist's much more severe problem. Will it get better? I doubt it. Our profession denied these injuries for a long time and only now are we talking about it openly.

John Hirshfeld Jr, MD (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, PA):

Never fear, the neck can be a remarkably resilient structure and seemingly awful symptoms can resolve completely with conservative management.

I have struggled with my neck for years. I abused my neck playing interscholastic soccer for 8 years during which it was in vogue to do what are now recognized as inappropriate neck muscle-strengthening calisthenics (bridging: I expect the other old guys will remember that badly conceived exercise). Thus, I don’t believe that I can blame my neck problems entirely on 45 years of wearing lead (including 10 years before the two-piece leads were popularized).

If you don’t have an identifiable structural problem in your cervical spine, you have a very good shot at getting better with conservative therapy. In addition to anti-inflammatories, the key therapeutic intervention is restricting motion while healing is underway. That interrupts the vicious cycle of root irritation, swelling, and more pain and more dysfunction.

The immobilization strategy means you have to go in the cervical collar (which means that you get to do nonstop explaining to sympathetic listeners). However, once in the collar you will very promptly feel better and realize its importance.

Two aspects of going in the collar:

1. Do it sooner when a flare-up starts, even though you don’t want to.

2. Stay in it longer than you think you need to, even though you want to stop discussing it with everyone.

One other aspect of working in the lab: keep your monitors as low as possible. Craning your neck to look up at the monitors pours gasoline on the fire.

My neck has acted up multiple times over the years including one episode where I had a C8 motor radiculopathy (which got my attention at the time). I see the head of the spine service at Penn. I was sure that motor dysfunction meant I had crossed the line to needing surgery. He assured me that I would get better with conservative therapy, and I did.

The moral: find a good spine surgeon who knows when and, importantly, when not to intervene.

Sound familiar?

After 40 years of this, there still is no scar on my neck.

James A. Goldstein, MD (Corewell Health, Royal Oak, MI):

First: I have a conflict of interest, as I am involved with the Protego device invention and development. Therefore, the following should be considered with that relationship and potential bias so disclosed.

That said, it is now proven that by using enhanced shielding technologies, one can reduce radiation exposure dramatically—the extent of protection may vary with the device (I suggest to review and compare PUBLISHED peer-reviewed data to best determine: the several recent peer-reviewed publications by Dr. Rizik that Tim Henry refers to show 99% reduction with Protego, with two-thirds of cases “zero exposure” by RaySafe dosimetry).

Increasingly our colleagues using such protection are working without orthopedically burdensome lead aprons (the State of Michigan has, by independent physicist testing, validated Protego can be used without lead aprons).

Understanding that at present getting hospital administration to open their checkbooks can be challenging and time delayed, Image Diagnostics Inc, the company manufacturing, promoting. and selling Protego, has recognized this issue and has a program that will place a system without capital equipment outlay. The financing is covered by a program that is paid for by the per-case disposable. This may be a pathway to explore for more-timely implementation.

Time to “stop getting radiated and get the lead off our backs.”

Augusto Pichard, MD (Abbott, Washington, DC):

I agree with all the comments above. Lead free is the objective. Industry is also working on X-ray free!

I was in the cath lab full time for about 45 years and was fortunate to have no major spine issues, but like Steve Ramee recommends, I did core-muscle exercises every day all along.

I do have spinal stenosis, significant but without symptoms. I remain fully active and walk more than 5 miles a day.

For cervical spine, I would recommend you also consider using the inflatable neck brace. Several of my colleagues have used it with great results. You initially inflate for 5-10 minutes, two to three times a day, then gradually decrease until you reach once a week. It creates effective traction and opens up the spaces.

Arnold Seto, MD (Long Beach VA Medical Center, CA):

We have the Protego system in our lab, and it is a godsend for those longer CTO cases with obese patients. Physicians, nurses, and techs all love it, even if it takes a little longer to set up.

As chair for SCAI’s Advocacy Committee this year, I have been exploring ways we could help advocate for safer radiation protection now that these newer systems do not require us to wear lead. I was hoping that there would be some regulatory guidance on how long someone could be asked to wear lead, but unfortunately such studies and regulations do not exist. Notably:

1) While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and Nuclear Regulatory Commission require 0.5-mm lead equivalent radiation protection, OSHA does not have a standard that sets limits on how much a person may lift or carry.

2) The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has developed a mathematical model that helps predict the risk of injury based on the weight being lifted and other criteria.

3) The UK Health and Safety Executive suggests that lifting/carrying up to 20 kg at the shoulder is associated with a “low risk of injury.” Most lead aprons weigh between 5-25 lbs which is well within this range. However, the risks of chronic use are evident to all of us, especially in the context of the injuries described on this email chain.

With the lack of regulatory rules mandating use, we have to advocate for these systems in our facilities.

The Organization for Occupational Radiation Safety in Interventional Fluoroscopy (ORSIF) has an economic analysis available:

- 70% reported lumbosacral problems

- Of those who had been in practice for at least 5 years, 85% had at least one musculoskeletal problem

- The economic cost of musculoskeletal disorders for interventional nurses and technicians amounts to $12,000 USD

- For interventional physicians, these disorders are valued at $45,000 USD

These estimates are quite low and underestimated, and the authors themselves note that replacement costs of physicians may be more than $1 million.

Ultimately, these purchases will be local decisions, and Protego's new offer of avoiding capital outlays will be helpful. I suspect as more employed physicians start having workers compensation claims against their employers, that will be a major driver of uptake, but that would take time. If we had a better economic analysis which demonstrated the reduction in sick leave/workers comp/replacement costs with the use of these devices, that would go a long way towards convincing the hospital executives to invest in this equipment to protect their physicians, nurses, and techs.

Paul S. Teirstein, MD (Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA):

One other option for payment is for one or more senior physicians to offer to donate a radiation protection system to the hospital. It’s annoying to have to do this—and expensive—but it’s tax deductible. At Scripps we found this to be a very good way of getting the administration’s attention. After buying one for the hospital, they were guilted in to buying additional systems.

Kenneth Rosenfield, MD (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston):

I’m so glad this issue has made it to "Conversations with Mort.” It’s long overdue.

We all need to focus more on occupational health: not just for physicians, but also for our nursing colleagues and techs, who are both exposed to radiation and have the same potential orthopedic issues that we do. In 2009, Lloyd spearheaded a document about these occupational risks, and when I was president of SCAI, Manos Brilakis undertook a screening program for cataracts at the annual meeting. Kudos to them, Jim Goldstein, Dave Rizik, and many others who have been champions.

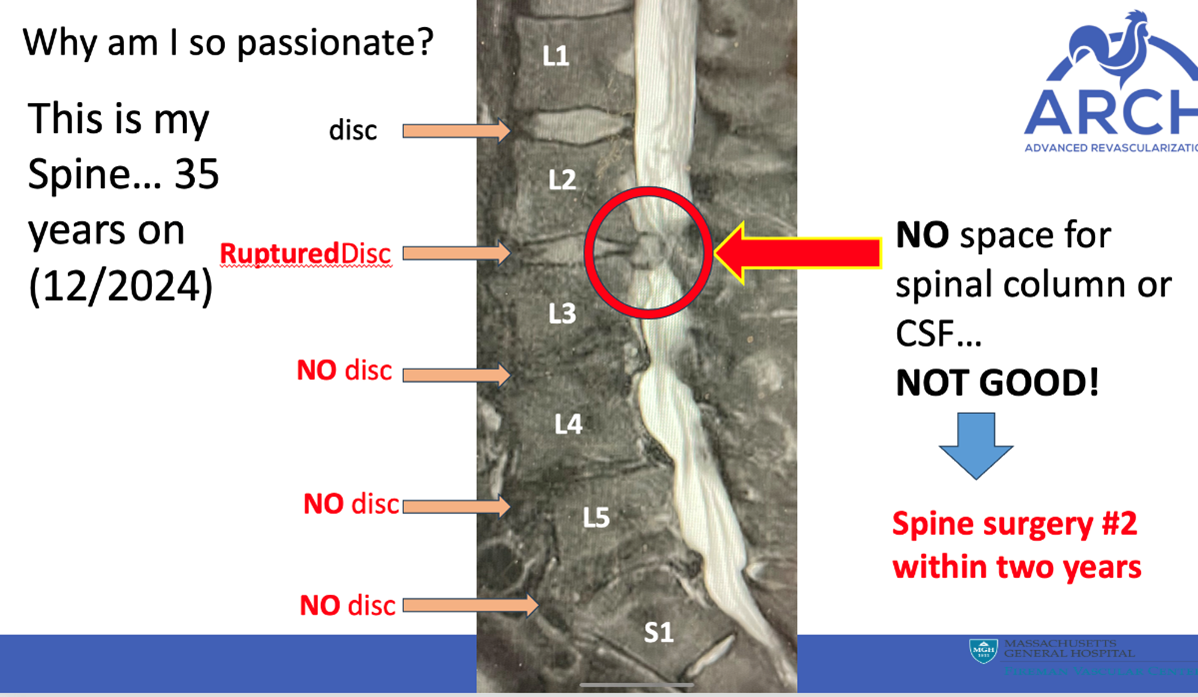

As is the case with too many of us, this is personal. I returned to work and the cath lab in late March following a 3-month medical leave related to lumbo-sacral spine surgery (diskectomy/laminectomy). This was my second back operation in 2 years. Leading up to the surgery, I was unable to stand up straight and was in constant severe pain. I had “pushed through” the last 6 months until it was intolerable.

Speaking to colleagues in the wake of my surgery, I am astounded to learn that MANY—seems like 30-40%—have actually undergone back or neck surgery, and most of the remainder are plagued with discomfort. Joint replacements are also prevalent. And some, like Chip Gold and Ted Deithrich, have died from radiation-related cancer.

I have now become a passionate advocate for fixing this problem. There ARE solutions and we DO have the technology, and it is developing rapidly. Protego, Rampart, EggNest, Zero-Gravity have all been mentioned. We have Rampart, although use is sporadic. I use it for balloon pulmonary angioplasties and some coronary cases. In those cases, I am the only one who goes “lead free” —everyone else wears lead. Radiaction is another solution that is now becoming available and is US Food and Drug Administration approved as a Class II device. It promises to completely block the radiation/scatter at the source (the X-ray tube and the image intensifier), thereby protecting everyone in the room, including techs and nurses for every case. This works not only for coronary cases, but also structural, peripheral, and EP cases, where some other technologies are challenged. (Full disclosure: I have chosen to join Radiaction as a compensated advisor, as I am convinced the best ultimate solution is to stop radiation and scatter at the source).

As a specialty, we need to protect ourselves and our staffs. We need to educate hospital administration and big iron companies and be very clear about how important this is to us. All parties need to know that, in order to help our patients, we need to be healthy ourselves!

Kudos to Jim Hermiller, who has committed to work intensively on this issue during his upcoming SCAI presidency. As leaders in the field, let's all commit to supporting Jim’s initiatives.

Gotta go do my core strengthening! Stay healthy all!

PS: Attached below is the MRI of my spine pre-op. I had the privilege of delivering the talk on occupational hazards at Jas Singh’s ARCH Symposium. I am happy to share some of those slides if someone wants to review, or even use them for a talk.

Dean Kereiakes, MD (The Christ Hospital):

There is no single issue more important to the collective cath lab “family” of physicians, nurses, and techs. We have evaluated three systems, as Tim Henry pointed out—EggNest, Protego, and Rampart—in my absence during the month I spent in the hospital recovering from emergency cervical spine decompression. My first urgent discectomy was a week before I turned 38 years old due to acute, severe left foot drop. I was back in the lab shortly thereafter, and every time I would get lumbar spine or cervical sciatic pains, I would start prednisone 30 mg daily with a taper over 7-10 days and I was “back in the game.”

After a busy late January this year, I had a 15-minute episode on the weekend of February 3rd where my arms were clumsy and I had trouble standing. I took 30 of prednisone. Monday the 5th I woke up with a right foot drop and while putting on my scrubs to go to the lab, a horrible pain came over my upper back and I couldn't effectively use my arms, then I couldn't stand. I was taken by EMS to the hospital and over the next 18 hours got 80 of Decadron and 320 of Solu-Medrol before being urgently taken to the OR. I began to “posture” like a praying mantis with my arms flexed up, my wrists flexed down, and hands/fingers clenched. I couldn't move my legs. I became a functional quadriplegic. I was fortunate—blessed—to have urgent posterior decompression of my entire cervical spine. Post-op, the left side came back rather quickly, but I had no use of my right hand and a paralyzed right leg. After a month in the hospital with intensive rehab I went home with a walker and a box of red rubber catheters to straight cath myself. All of these essential functions have returned, by the grace of God, and I plan to start seeing some patients in the office in May, gradually. I walk with a cane that I can't wait to get rid of.

This event was the product of wearing lead aprons during ~30,000 procedures over ~40 years. Lead used to be at least 30 pounds in the days of “bailout” atherectomy and during thousands of the procedures that many of us performed. Our hospital has rapidly moved to buy lead-free radiation protection, and I will do everything I can to get back into the lab once that is in effect. OSHA protects assembly line workers at Ford and GM, but not doctors and other healthcare professionals? This is clearly a worker's comp issue and a workplace safety issue, and the time has come for a collective mobilization of everyone on this chain and their associates. Hospitals that do not move promptly will be forced to move by the wave of class-action suits that will come in the next few years. Tim Henry and I have younger partners in their 30s who have already had cervical discectomy. This must change and we must lead that change. I am completely in support of the SCAI initiative and Jim Hermiller's commitment to this issue. Collectively we can get this done!

Duane Pinto, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and JenaValve Technology, Boston, MA):

I am surprised at how many of us have had cervical/lumbar disease fixed (amongst a crew who do what we do: living with pain, self-medicating) in our 30s. I too have had C5-C7 fusion in my 30s for pain, weakness, triceps wasting. This isn’t rotator cuff, carpal tunnel, tendinitis stuff. People are disabled because they have to wear a wrist brace—we don’t do that.

We all know “orthopedic injuries” for interventionalists, but I wonder if identifying and describing the type, severity, and early onset of these is also important. Showing we degenerate faster and more severely is important, not unlike seeing a patient in their 30s with their first MI.

David Rizik, MD (HonorHealth, Scottsdale, AZ):

Let me begin by disclosing I am a consultant to ECLS, who manufacture a shielding system. And I have worked closely with ORSIF over the past year on heightening awareness as to this issue.

I am saddened to hear all the stories of orthopedic and other injuries. I am delighted to see the outpouring of support mandating a change for more protection in the lab. We must get the lead completely off our spine! There is now a surfeit of data that confirm we can accomplish this, safely, in the cath lab.

VAS Communications and I have recently produced a documentary on this very subject: Scattered Denial. It started streaming in April and will air on PBS this summer. In the documentary, I traveled and met our colleagues from all over the country who have suffered from cancers and orthopedic injury as a result of our passion for being interventional cardiologists. I met families who have lost loved ones from radiation-related cancers who had worked in the lab.

Please keep the heat on CEOs, hospital systems, and our societies to mandate a change. Bottom line, I believe all new labs must be fitted with advanced protection systems. All existing labs must be retrofitted. As I have stated recently in editorial form in JSCAI, this not an "aspirational goal but a moral imperative."

Photo Credit: David Rizik, Chris Wooley, and Wayne Dickman (co-producers of Scattered Denial)

Henry:

Everyone on this list should watch Scattered Denial. Should be required viewing for cardiology fellows and hospital administrators as well!

All of us at the 2024 SIF meeting saw the previews/highlights. Those of us that have spent years getting radiation/orthopedic stress need to advocate strongly for our younger colleagues and cath lab staff!

Michael A. Kutcher, MD (Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Winston-Salem, NC):

I will add my story to this interchange in hopes that it helps.

I played contact sports in high school and college and worked four summers as a trackman on the Penn Central Railroad during my college years. So, I felt I could be prone to neck/back injury and was attuned to the consequences of wearing heavy lead aprons. I thought I could preemptively avoid these injuries by regular exercise—both running and resistance training. Unfortunately, I tended to use heavier weights and rigid equipment like the Roman chair for my back. In retrospect, I had a “fool” as a personal trainer—me—thinking I could still do the unsupervised exercises of a younger man.

In 2005, at the age of 56 and 26 years into my career, I had severe right radiculopathy due to a herniation of L4-L5 that did not respond to medical therapy. The pain was unbearable and required a microdiscectomy. I thought my career was over. But I wised up and got a “real” personal trainer to help me recover and learn to exercise safely. I was able to get back into the cath lab within a month. I did well until 2015, when I had another right-sided herniation one disc down from the previous site. Fortunately, it responded to prednisone and NSAID therapy. To date, I have been stable, but I am still careful when I feel any back twinges.

What were the consequences of my back injury? First, I decided to not get involved in structural heart interventions but to just concentrate on complex coronary interventions. So, I feel my interventional career was incomplete. Second, I dropped off the STEMI call schedule in 2017 at the age of 68 and then totally left the cath lab in 2019 – shortening my active interventional career by 2-3 years.

What did I learn from my injury? I realized the importance of a professional personal trainer to guide me in proper exercise technique to protect my back. I continue to exercise on a regular basis. In addition, I now get my aerobic exercise by using an elliptical machine instead of running on hard surfaces.

I agree with the many great preventive suggestions by colleagues on this exchange. I would like to add one more. New interventional cardiology fellows should be offered a formal introductory program that emphasizes the importance of regular and safe exercise to stabilize and protect the neck and back. This could include a group meeting with a personal trainer to outline proper neck and back exercise techniques. The options of yoga and Pilates should also be outlined.

The Bottom Line From Mort Kern:

Like all my interventional colleagues, I commend the great efforts of David Rizik, Jim Goldstein, and the many others working to develop safe and protective lead-free options. Hopefully, the present and future interventional cardiologists will not have to suffer from these life-altering occupational dangers. I join with Dr. Rizik in the imperative that we must all be advocates for change.

Conversations in Cardiology is a collection of first-person perspectives from leading voices in the field of cardiology. It does not reflect the editorial position of TCTMD.

Jim Collins

Kira Stephenson