Why I Support the Junior Doctors’ Strike: It’s in Our Best Interests to Listen

Most say they still love medicine, but undervalued, underpaid, and saddled with debt, our future physicians deserve to be heard.

In 2018 and again in 2019, I had A-level (high school) students spend a fortnight shadowing me at work in preparation for their (ultimately successful) applications to medical school. Keen, bright-eyed, and motivated, these young people had huge plans for a future in medicine unburdened by cynicism and negativity. Imagine my despair, therefore, when earlier this year I learned that both had left their respective programs and transferred to alternative courses within 12 months. When I asked why, they essentially told me the same thing: “We can see the writing on the wall for junior doctors and it does not look good.”

The rest of the world, watching the junior doctors’ strike in England, is likely wondering the same thing all of us are asking ourselves: What on earth is going on with medicine in the UK? How did we get to the point where some of the brightest and most hardworking younger members of our society have become so disillusioned with this profession?

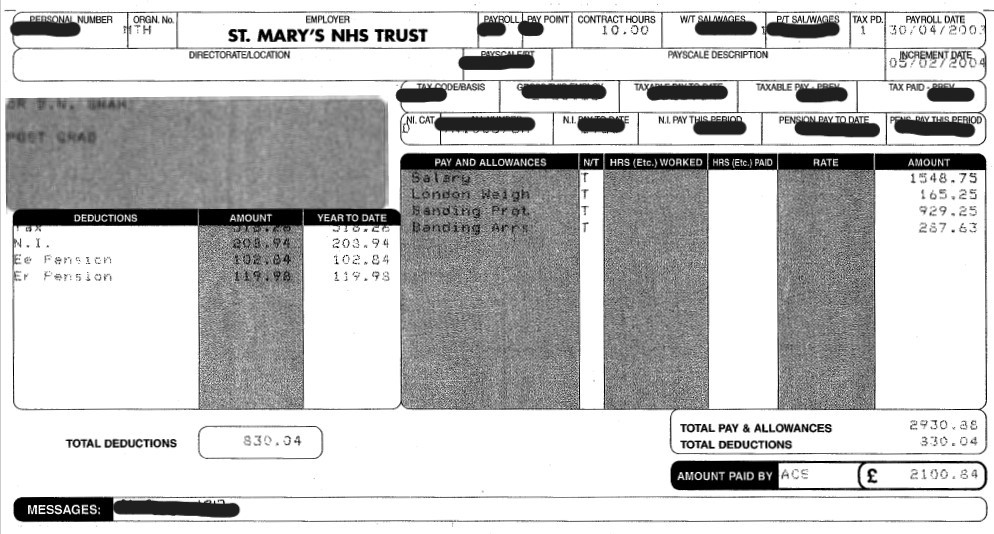

Here is my payslip showing £14.09 per hour. Even if we take pay on top of basic into account, it still comes out at £14.31 per hour (2747.96÷4÷48). I studied at university for 7 years, have >£70,000 student debt and work to save lives 48 hours a week. I deserve more. pic.twitter.com/yShR6L12QM

— 🇺🇦 Annie #BMADoctorsVoteYes ✊ (@Anniedroid_) April 13, 2023

Here, the term “junior doctor” is used to describe any doctor in training who has not yet become either a consultant (secondary care) or a fully qualified general practitioner (primary care). This could refer to a 23-year-old newly qualified doctor or someone in their late 30s who has completed higher specialist training and is undertaking a final fellowship before commencing a permanent consultant post. Junior doctors could be the anaesthetist and surgeon removing your appendix, or the ones helping you give birth to your child, breaking bad news about a diagnosis, or performing emergency cardiac resuscitation.

After the global financial crisis in 2008, the salaries of many public sector workers, including doctors, were frozen, preventing them from even keeping pace with inflation. By now, pay freezes in England have been in place so long that, in real terms, junior doctors have seen at least a 25% fall in their pay, such that they’d need a salary increase of 35% just to restore their pay to 2008 levels.

Many junior doctors have taken to social media to share their monthly pay slips, prompting me to dig out my own from 20 years ago. Back in April 2003, as a first-year doctor my take-home pay was £2100. This is identical to, and in some cases more than, the pay being received by junior doctors today! Think for a minute about how much everything else in the world has gone up in price over those two decades: the average house price in England has gone from £123,258 in April 2003 to £310,000 today, and 1 litre of petrol was 78 pence, whereas it is 150 pence today. The fact that salaries from April 2003 and April 2023, for the same job, are even remotely comparable is truly staggering. It easy to understand why junior doctors feel aggrieved at their current salary.

The world, too, has changed for junior doctors. When I was at medical school in the mid-to-late 1990s, medical education was free for British citizens and there were means-tested grants available for students from less affluent backgrounds to support them during their studies. As a result, newly qualified doctors were entering the workforce with relatively little debt. Back then, first-year doctors, called “house officers” here, received free hospital accommodation. Moreover, being a house officer meant joining a “firm” typically consisting of a consultant, registrar (resident), senior house officer (senior intern), and house officer (intern). For the next 4 to 6 months of our placements, this was your team, your “family at work” providing essential camaraderie and support—for the good times when you had a real treatment success, but also for the bad and the difficult. No doctors ever forget the first time they lose a patient under their care, or having to break that news to the family.

By comparison, the situation for junior doctors today is almost unrecognizable. University is no longer free in England, and medical students pay thousands of pounds each year in tuition fees. A debt load for a newly qualified doctor typically exceeds £75,000. Ironically, the interest on student loans is disproportionately high, leading to the ludicrous situation wherein, after working for several years as a physician and paying back the loan, the actual debt load increases as the interest charged on the loan exceeds the loan repayments made.

If you are wondering why we are striking.

— Dean (@Dr_DeanS) April 10, 2023

This is my payslip right at the very end of my second year as a doctor. pic.twitter.com/ccrhomiacA

Free accommodation for junior doctors has disappeared, as has the “doctors’ mess,” which in days of old was the hospital space for doctors to unwind with their peers. The mess was an invaluable resource for junior physicians on a temporary placement in totally unfamiliar parts of the country without family or social supports. And, for a range of reasons, the “firm” structure that allowed for so much camaraderie and mentorship is all but lost. A huge factor here is the extraordinary turnover of patients—some hospital administrators have created dedicated shifts for junior doctors to come in to support other junior doctors solely to handle the paperwork. It’s not uncommon now to read a discharge summary for a patient that includes a caveat: “Doctor did not meet the patient.”

For many, COVID-19 was the final straw. Junior doctors were universally redeployed to intensive and high-dependency care units as well as inpatient wards to care for patients with SARS-CoV-2, placing enormous physical and psychological stress on young people ill-prepared for that emotional toll. Many, tragically, paid with their lives. Those who survived face different challenges. A survey by the British Medical Association (BMA) in 2021 found that over 40% of junior doctors were feeling depressed, anxious, or burnt out after the pandemic and 60% reported higher levels of fatigue then they would consider normal for themselves.

The salary shortfalls, the isolation, the mental health crises: all come in the midst of what many see as an utter lack of control over their lives. Junior doctors often have very little say over where they work, what hours they keep, and there are few if any considerations for those with disabilities, childcare, or family care commitments. Even for major life events such as weddings, funerals, or significant postgraduate exams, it can be extraordinarily difficult to secure time off work. Medical couples may be given placements that force them to live apart or travel hours in opposite directions to their place of work. Whereas doctors in the past may have suffered in silence, today's doctors are finding their voice.

In March, 36,955 members (77.5%) of the 47,692 junior doctors within the BMA cast a vote on whether to take industrial action over pay and conditions, and an overwhelming 98% supported this. Unlike a prior strike in 2016, on this occasion they also voted to withdraw emergency care, with provisions in place that hospitals could recall their junior doctors if a patient's safety was clearly at risk. That first strike lasted for 3 days.

My mid-pandemic payslip. Less than £14 an hour for my 9-5 shifts, resulting in under £1850 a month net. This, for working as a qualified doctor, through COVID, after 5 years in medical school. Oh, and I checked my student loan debt this morning - £78,571.14 #JuniorDoctorsStrikes pic.twitter.com/O6n7oK7X7n

— James 🦀 #BMADoctorsVoteYes (@pjamestheleast) April 13, 2023

The second, this week, lasted 4 days, ending April 14th. To ensure ongoing care and treatment for hospitalized adults and children, consultants like me have stepped in to cover for their junior colleagues who are on strike. This has meant the cancellation of hundreds of thousands of outpatient clinic appointments and elective operations, including urgent procedures for patients with cancer and heart disease. I myself have just finished several days of “acting down” to provide ward cover for our cardiac inpatients in Southampton General Hospital: I support the junior doctors wholeheartedly in their demands for improved pay and working conditions. Notably, despite the disruptions, polls across England have repeatedly shown that support for the strikes amongst the general public is high.

Most will tell you that, despite everything, they have not lost their love of medicine but are fed up with the system, with their employer—the National Health Service (NHS). The NHS, despite all it does for our country, has in too many places become a terrible employer; it has failed to keep up with the times, to protect its employees, to listen, and to treat its staff with sufficient respect or care.

Junior doctors know their worth—there is a significant global shortage of medics, and this supply/demand imbalance is only set to worsen in the coming years due to a combination of growing populations, ongoing challenges in access to medical education, and premature retirement or change in careers due to burnout in Western countries. The World Health Organisation estimates that there will be a global shortage of 10 million healthcare professionals by 2030—at least half of this number will be a shortage of doctors. Disillusioned in the NHS, many are emigrating and an unprecedented number of doctors in training are leaving medicine altogether. Saddled with debt, treated like children, underpaid, and undervalued, our junior doctors are fighting not only to improve their conditions but also to overhaul the system. It is in all of our interests to ensure that they succeed.

Off Script is a first-person blog written by leading voices in the field of cardiology. It does not reflect the editorial position of TCTMD.

Benoy Shah, MBBS, MD(Res), is a consultant cardiologist at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, England, and the clinical lead…

Read Full Bio

Comments