AI in Cardiovascular Imaging and Interventions: Boon or Bane?

A session devoted to the technology at EAPCI 2026 covered the manifold possibilities, but also the pitfalls to avoid.

MUNICH, Germany—Artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to expand its reach in cardiology, though that promise must be accompanied by caution, researchers stressed this week at the 2026 European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Summit.

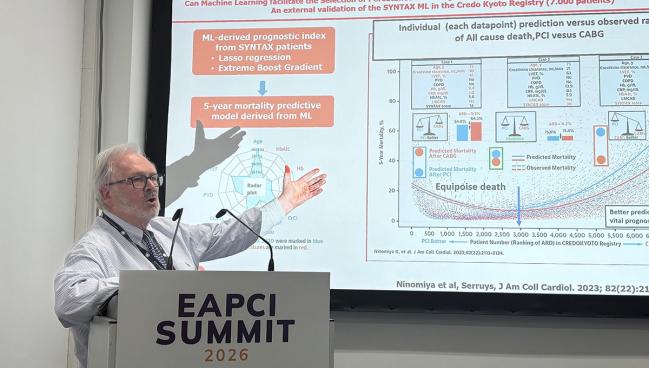

During a session devoted entirely to AI, Patrick W. Serruys, MD, PhD (University of Galway, Ireland), gave a detailed overview of the technology’s various forms and applications—both current and future—in cardiovascular interventions.

AI “encompasses any technique or system that allows a computer to mimic human behavior: feeling, thinking, acting, and adapting,” said Serruys. It takes various forms, from machine learning to large language models, among others. When applied in medicine, the tools can be used to more quickly process data, pinpoint diagnoses, predict outcomes, guide interventions, and streamline workflow.

To illustrate the breadth of AI, Serruys summed up the many projects being done at the University of Galway’s CORRIB Core Lab.

For instance, as described in a 2023 European Heart Journal – Digital Health paper, he and his team used machine learning to delve into 75 preprocedural factors and identify which among them predict 10-year mortality in the SYNTAX study.

The project revealed a surprise predictor: gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). Serruys said he was skeptical of the finding at first, but that he came to understand that it makes sense. GGT “is a marker of systemic oxidative stress, which has an impact on plaque progression, destabilization, and heart failure,” he explained. In SYNTAX, patients with high GGT had a 10-year mortality rate of 32.7%; for those with low GGT, 10-year mortality was 23.5%. The researchers went on to externally validate their model, which was informed not only by GGT but also by C-reactive protein, patient-reported preprocedural mental status, and glycated hemoglobin, using data from a Japanese registry.

Planning is everything. Patrick W. Serruys

Other applications include interpretation of coronary CT angiography (CCTA) to guide interventions. Yet, as is often the case for emerging technologies, AI is not without its hiccups. Experts at the US National Institutes of Health “are increasingly concerned with the lack of concordance among these various AI softwares when analyzing the same CCTA,” Serruys cautioned, urging physicians and professional societies to persuade companies that their tools have to provide consistent results.

Still, he said, AI can be useful ahead of PCI in simulating anatomy, flow, and postprocedural results of stenting. It also can be viewed through virtual reality as a way for heart teams to digest the information prior to the procedure or even in the cath lab. Similarly, the technology can be applied in the setting of valvular disease and structural interventions, added Serruys.

He emphasized that AI, while promising, must be approached carefully. Cons include ethical concerns like data privacy; the need for not only tools but also training; the possibility of bias that must be mediated through validation across datasets; and the challenge involved in trusting results that emerge from what can be—to human understanding at least—opaque AI-based decision-making.

Strides in Intravascular Imaging

Christos Bourantas, MD, PhD (Barts Heart Centre, London, England), focused his talk on the current state of AI in cardiovascular imaging, specifically IVUS and OCT.

“AI has revolutionized intravascular imaging processing. We can now [quickly] and accurately process large imaging datasets, and we have methodologies that have been incorporated into intravascular imaging systems for data acquired during routine PCI.” Proof-of-concept studies have shown that these systems can help predict PCI results. They can characterize both plaque composition and lesion severity, and histology has been used to train the software to recognize what constitutes high-risk features.

However, there is much work left to be done in this area “because most of the solutions for [intravascular imaging] still make mistakes as they have been trained in small datasets,” said Bourantas. “Despite evidence showing the feasibility of AI to predict the final PCI results, in patients at risk, we don’t have a robust solution that can be used in clinical practice.”

AI cannot replace the cardiologist’s own judgement, he emphasized. “If you are going to apply it in humans, we need to be sure that somebody has gone through the code and has checked it. [To] get to the level to trust the AI estimation more than our expertise, we have to be 100% sure it has been proven in outcomes studies. And we are not yet there in intravascular imaging.”

We have a lot of lights but also shadows, so we have to move carefully. Raffaele De Lucia

Session co-moderator Carlos Collet, MD, PhD (Cardiovascular Center Aalst, Belgium, and Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY), said the amount of information presented on AI could be overwhelming. “You basically described everything that happens from the diagnosis to the follow-up,” Collet said to Serruys, asking where AI is most helpful.

“Preplanning—planning is everything,” Serruys quickly answered. AI can be used to “interrogate [just] about everything: what is going to come during the procedure, what is going to be the result of the procedure. . . . You can really fantasize about what you are going to do the next day.”

Collet, for his part, drew attention to another role for AI: reducing variability.

When looking across trial databases, “I realized that the biggest problem we have in generating evidence is the variability in [patient] care,” he said. In the United States and Japan, for example, cases are handled very differently despite having the exact same diagnosis.

Serruys agreed that AI will, with time, enable more consistency. Already, many interventional cardiologists are using AI in their work, he said. “It’s something that is a real tsunami in our practice. . . . When I review a trial [I’m involved in] daily, I dictate my questions to the computer, then ChatGPT polishes my English and polishes whatever I’ve done. It then stratifies that for questions for tomorrow.”

The tools also are able to take notes easily and quickly after a case is completed, he added. “AI is here to help us improve the workflow,” with that efficiency allowing for more face-to-face time with patients.

Raffaele De Lucia, MD (University Hospital of Pisa, Italy), who co-moderated the session, asked attendees what will happen when an AI tool gets a class I recommendation in clinical guidelines. “How can we imagine moving [AI] to this new setting?”

This question is pertinent but not unprecedented. Other proprietary technologies, such as CCTA software, have successfully been adopted in clinical practice, so AI could follow the same path.

De Lucia closed the session by saying that AI presents many opportunities, though that came with a caveat. “I think that AI will really reshape our clinical practice,” he commented. “We have a lot of lights but also shadows, so we have to move carefully.”

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Serruys PW. The role of AI in cardiovascular interventions. Presented at: EAPCI 2026. February 19, 2026. Munich, Germany.

Bourantas C. AI-based integration of intravascular imaging in PCI. Presented at: EAPCI 2026. February 19, 2026. Munich, Germany.

Disclosures

- Serruys reports relevant connections to Meril Life and Novartis.

- Bourantas reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments