Aspirin Fails to Prevent Onset of Dementia in Diabetic Patients: ASCEND

There was a trend toward protection, suggesting a larger study with more events might be needed to know if aspirin is helpful.

Aspirin use in patients with diabetes but without cardiovascular disease does not have any significant protective effect on dementia or cognitive impairment, according to the results of the large ASCEND trial.

Using both broad and narrow definitions of dementia, investigators observed trends toward fewer events among those treated with aspirin, however, and they suggest that trials with more incident dementia cases are needed to rule out any modest benefits of aspirin over the long term.

To date, no randomized trial has shown any convincing evidence that aspirin has a positive effect on the incidence of dementia or cognitive impairment, but there are arguments to be made that it might help as well as harm, said lead investigator Jane Armitage, MBBS (University of Oxford, England), who presented the results of ASCEND earlier this week at the virtual American Heart Association 2021 Scientific Sessions.

“When we consider the brain, the effects of aspirin may go in either direction,” said Armitage. “It may improve cognitive impairment through the avoidance of ischemic strokes and transient ischemic attacks—either overt or silent ones—but it may equally increase impairment through an increased risk of intracranial bleeding or even microbleeds into the brain, which are also silent.”

In a prior analysis of the ASPREE trial, which along with ASCEND was part of a series of trials that proved to be aspirin’s undoing for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, investigators reported that aspirin had no effect on the risk of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or cognitive decline compared with placebo.

Broad and Narrow Definitions

ASCEND included 15,480 patients (mean age 63 years; 63% male) with diabetes but without cardiovascular disease who were randomized to aspirin 100 mg daily or placebo. Participants were followed for a mean of 7.4 years during the trial and for an additional 1.8 years after it was completed. Investigators tracked two definitions using electronic health records, the first a broad definition that included outcomes such as dementia, cognitive impairment, delirium/confusion, use of dementia medications, or referral to a memory clinic or geriatric psychiatry. The second, narrow definition was a diagnosis of dementia.

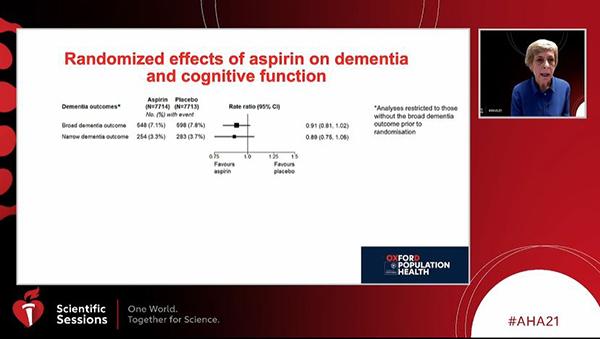

For the broad dementia outcome, there were 548 events among 7,714 patients treated with aspirin (7.1%) compared with 598 outcomes in 7,713 patients who received placebo (7.8%), a nonsignificant difference. In the aspirin group, 254 patients were diagnosed with dementia (3.3%) compared with 283 participants in the placebo arm (3.7%), also a nonsignificant difference. With aspirin, there was no significant impact on cognitive function tests.

During the late-breaking science session, Armitage said the confidence intervals around the nonsignificant 9% relative reduction in risk of dementia (broad definition) were wide. “In order to detect what might be a plausible and indeed important benefits of aspirin, in the order of 15% to 18%, trials with a larger number of incident dementia cases would be needed,” she said.

Amytis Towfighi, MD (University of Southern California, Los Angeles), who discussed the results following the presentation, noted that there are observational studies suggesting a lower prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in people who regularly take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for rheumatologic diseases. Like Armitage, she noted that aspirin has been posited as a preventive agent for dementia because it can reduce inflammation, which is a driving force in Alzheimer’s disease, and by potentially reducing amyloid pathology.

Still, the trial was negative, as was ASPREE, she noted. In terms of what’s next, Towfighi suggested that there might be specific subgroups who might benefit from aspirin, pointing to a smaller primary prevention study in Japanese individuals that showed aspirin reduced the risk of dementia in women.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Armitage J, on behalf of the ASCEND investigators. Effects of aspirin on dementia and cognitive impairment in the ASCEND trial. Presented at: AHA 2021. November 15, 2021.

Disclosures

- ASCEND was funded by the British Heart Foundation, the UK Medical Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, with minor financial support from Bayer, Abbott, Mylan, and Solvay.

Comments