Body Fat Distribution Influences Cardiovascular Age

Where people accumulate fat appears to have a greater impact on how their hearts age than does BMI.

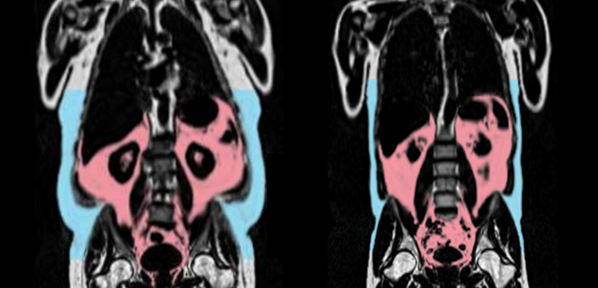

Two MRI scans, showing the person on left with more visceral fat (in red) and subcutaneous fat (in blue). Photo Credit: AMRA Medical

How fat is distributed around the body influences cardiovascular aging—and is more informative than body mass index (BMI)—in middle-aged individuals, with some differences between men and women, a UK Biobank analysis indicates.

The study, led by Vladimir Losev, PhD (Imperial College London, England), was published online Friday in the European Heart Journal.

Senior author Declan O’Regan, MBBS, PhD (Imperial College London), told TCTMD his group has been interested in exploring cardiovascular aging by imaging the heart, which gives a direct look at the physiology of the heart as well as the circulation. Machine learning processes those images to predict a person’s biological age, which is compared with chronological age to determine how well a person’s heart is aging.

In this study, Losev, O’Regan, and colleagues explored the relationship between cardiovascular aging and body fat distribution. “Fat in certain parts of the body is particularly harmful to the cardiovascular system, but how that actually affects the heart and circulation hasn’t been totally clear,” O’Regan said.

They found that visceral adipose tissue volume and liver fat fraction had particularly strong relationships with cardiovascular aging, assessed using the difference between a person’s chronological age and their age predicted by imaging measures related to vascular function, cardiac motion, and myocardial fibrosis.

The associations of visceral fat and abdominal adipose tissue with accelerated cardiovascular aging—ie, a greater age-delta, or difference between chronological and predicted age—were more robust in men than in women. Moreover, increased gynoid fat, the type that accumulates around the hips and thighs, was tied to protective effects—a lower age-delta—in women but not men.

“We show that fat distribution may underlie premature aging of the human cardiovascular system and that phenotypic differences between sexes modify these processes,” the authors say. “This work demonstrates the key role played by visceral adipose tissue and the distribution of subcutaneous fat in regulating biological age and highlights the potential value for novel therapies intended to extend health span through modifying adipose tissue function.”

Chronological vs Predicted Heart Age

The investigators examined data on 10,558 women (mean age 62.5 years) and 10,683 men (mean age 63.9 years) who underwent a baseline cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) scan and whole-body imaging to assess volume and distribution of body fat. Overall, women had more abdominal subcutaneous fat, muscle adipose tissue infiltration, and gynoid fat than men, with men having greater whole-body fat mass and volumes of visceral fat and android fat.

The strongest predictors of accelerated cardiovascular aging for both sexes together were liver fat fraction (β = 1.066), visceral adipose tissue volume (β = 0.656), and total abdominal adipose tissue volume (β = 0.616; P < 0.05 for all).

“We show how harmful visceral fat is, particularly in driving premature aging,” O’Regan said. “It’s probably one of the key reasons that visceral fat is bad.”

Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue volume (β = 0.432) and android fat mass (β = 0.983; P < 0.0001 for both) predicted poorer cardiovascular aging in men. And in women, greater gynoid fat mass was associated with more favorable cardiovascular aging (β = -0.499; P = 0.0066), with the relationship confined to those who were premenopausal versus postmenopausal women. “The fat around the hips and thighs probably is producing chemical signals that damp down inflammation,” O’Regan speculated.

We show how harmful visceral fat is, particularly in driving premature aging. Declan O’Regan

The researchers also found that worse cardiovascular aging was associated with increases in various biomarkers, including triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, total cholesterol, and direct LDL cholesterol, with greater HDL cholesterol levels appearing to be protective.

Moreover, cardiovascular aging seemed to be influenced by sex hormones, which “modify key aspects of nutrient sensing, metabolism, and fat depot regulation,” according to the researchers. Estradiol was associated with a worse age-delta in men, but not in women overall, although in premenopausal women, higher estradiol was tied to better cardiovascular aging. Greater concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin correlated with a greater gap between chronological and predicted age only in women, whereas more free testosterone was related to more favorable cardiovascular aging in both sexes.

When assessing the impact of physical activity, the researchers found that a higher volume of visceral adipose tissue had a greater adverse effect on cardiovascular aging in the presence of obesity when individuals were unfit versus fit. “But nonetheless, for everyone, having too much visceral fat was bad for you,” O’Regan said.

Fat Distribution Tops BMI

BMI was a significant predictor of cardiovascular age-delta, although the correlation was weaker compared with body fat distribution in both men and women.

“One key message I think from this study was that things like overall weight and body mass index really didn’t predict aging well at all,” O’Regan said. “I don’t think we can rely on those conventional measures. . . . I think techniques that actually tell us where the fat is, how much of it there is, how much is in a male distribution and a female distribution give you so much more useful information about the potential harm that fat is doing than just going on a set of scales. That gives you almost no useful information about the effect of bad fat on the heart.”

Of note, nearly one-third of women (31%) who were considered overweight on the basis of BMI fell into the normal range of whole-body fat mass. That figure was lower (11%) in overweight men, with fat mass reclassifying 23% into the obese category.

“Not only is BMI not a great predictor of the harmful outcomes of obesity, but also it can actually put people in the wrong overweight and obesity categories because it doesn’t know where the fat is,” O’Regan said.

These findings, the researchers suggest, could inform considerations around use of various medications. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, for instance, have been shown to specifically reduce visceral and liver fat in patients with or without diabetes. Other therapies, like sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and mitochondrial uncouplers, “might also have a role in modulating the pro-aging effects of adipose tissue function,” the authors say.

O’Regan said that it will be interesting in future studies to explore the effects not only of GLP-1 receptor agonists, but also of weight loss in general and gastric bypass surgery on cardiovascular aging and the development of age-related cardiovascular diseases. Some preliminary work, he noted, has shown that gastric bypass surgery leads to “quite pronounced” reductions in visceral fat.

“It’s not just kilograms of weight loss, it’s where you’re losing that fat that’s probably particularly important,” emphasized O’Regan.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Losev V, Lu C, Tahasildar S, et al. Sex-specific body fat distribution predicts cardiovascular ageing. Eur Heart J. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by the Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, all in the UK.

- O’Regan reports having received funding from Bayer AG and Calico.

Comments