Delayed Coronary Obstruction After TAVR: Prevalence, Causes, and Solution Explored for Deadly Complication

Experts say obstructions, while rare, need to be taken seriously as TAVR moves into lower-risk patients. The BASILICA procedure may help.

Delayed coronary obstruction is a rare complication following TAVR, but given its association with increased in-hospital mortality, experts are advising better prediction and prevention measures be taken, especially as lower-risk patients start to be offered the procedure.

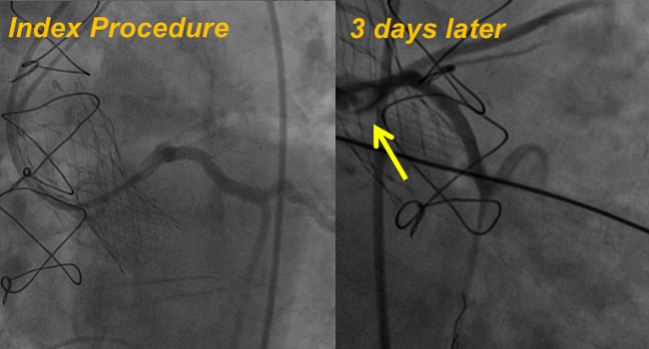

After observing two patients who had undergone successful TAVR in his lab return with coronary occlusion and die shortly after, Azeem Latib (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy), told TCTMD he was stumped. In one of the patients, occlusion had occurred despite operators taking the extra step of placing a coronary guidewire as a preventive measure during valve implantation. Indeed, procedural characteristics cannot provide peace of mind, Latib said, noting that for one of the patients, “pathology confirmed that a leaflet had occluded the coronary, but at the time of the procedure, we felt very comfortable.”

Curious as to the prevalence of this complication worldwide, Latib, along with lead author Richard Jabbour, MD (EMO-GVM Centro Cuore Columbus, Milan, Italy), and colleagues, collected data from more than 17,000 TAVR cases from an international registry of 18 centers between 2005 and 2016. Their results, published online ahead of the April 10, 2018, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, show a 0.22% incidence of delayed coronary obstruction overall.

There was a higher prevalence among valve-in-valve procedures compared with TAVR in native valves (0.89% vs 0.18%; P < 0.001) and with self-expanding versus balloon-expandable devices used during the index procedure (0.36% vs 0.11%; P < 0.01). Additionally, patients seemed to present primarily within the first week after TAVR (47.4% within the first 24 hours) or after 60 days (36.8%), with no patients reporting coronary obstruction between 7 and 59 days after TAVR.

About one-third of patients presented with cardiac arrest and just under one-quarter presented with STEMI. The left coronary artery was most likely to be the occluded vessel (92.1%), although the right coronary artery was obstructed in 26.3% of patients. PCI was the most common management option, yet it was more successful in the left main (80.8%) compared with the right coronary artery (16.6%). Overall, 50% of patients with delayed coronary obstruction died in the hospital.

There were no procedural differences between the patients who presented before and after 7 days from TAVR, but those presenting earlier were more likely to present in either cardiac arrest or STEMI (75.0% vs 21.4%) and those presenting later were more likely to show signs of stable or unstable angina (50.0% vs 8.3%).

‘It Can Happen’

“The surprising part was that we weren't alone—it was an issue that had been seen in other centers as well,” Latib said, guessing that their findings potentially underestimate the incidence of delayed coronary obstruction.

“This is something that we now know and have documented that it can happen,” he continued. “So even if you have a patient with high-risk anatomic features [and] even though the coronary flow looked great at the end of the procedure, they still could have a coronary obstruction. So any change in symptoms in the first week after the procedure needs to be taken, I think, more seriously.”

Tamim Nazif, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), who was not involved with the study, told TCTMD that “it is somewhat troubling that only about two-thirds of the patients met one of the classical risk factors that have been identified for acute coronary occlusion, so I think we need to continue to learn about what the risk factors are to see if this can be more accurately predicted and therefore prevented.”

Any change in symptoms in the first week after the procedure needs to be taken, I think, more seriously. Azeem Latib

The paper has “some intriguing data . . . about a possible impact of the depth of valve implantation, so maybe there are in fact important differences in the selection of valves,” he continued. “We have the two commercially-available valve systems, but others are coming. We need to learn more about whether there's truly a difference between them, so it may impact valve choice.”

The “final wild card,” Nazif said, especially in terms of later events, “is whether thrombus in the sinus or on the valve itself may impact [the risk of coronary obstruction] and the differences in medical therapy such as anticoagulation might [make] a difference.” As such, he said he thinks future research should focus on risk factors, the effect of valve choice, and whether medical therapies could mitigate risk.

Greater Implications for Lower-Risk Patients

In an accompanying editorial, Neal Kleiman, MD (Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center, Houston, TX), writes that as procedures like TAVR “become mainstream, it becomes critically important to recognize the associated infrequent complications as well as the frequent ones.”

Especially as TAVR moves to lower-risk patients, he says these results identify an operational wrinkle: operators in the study were only sufficiently concerned about acute coronary obstruction to have protected the LM ostium in 27.4% of patients who went on to have the complication.

The lower a patient’s surgical risk, “the more unacceptable it is to have a poor outcome” with TAVR because they have a surgical option, Latib said.

“As we become more aggressive with TAVR, we are likely to become more liberal in selecting patients with borderline anatomic features,” Kleiman writes. “Although uncommon, [delayed coronary obstruction] merits close attention given that the acuity of patients undergoing TAVR has consistently decreased since the procedure was introduced.”

It won’t be the deciding factor between TAVR and surgery, but a patient at risk for delayed coronary obstruction will likely receive a different course of post-TAVR therapy, Kleiman said. Findings from ongoing research on anticoagulation after TAVR will likely play into the treatment decisions for those at risk, he added.

For now, operators should “have a low threshold for maybe doing a CT or coronary angiogram and just making sure that nothing has changed with the coronary flow” in patients for whom they have any concern, Latib said. “In the past, we didn't think this could happen, so when patients complained of symptoms post-TAVR we in our own minds as physicians excluded this and weren't too concerned.”

Testing BASILICA

A possible answer for preventing delayed coronary obstruction after TAVR might be a new procedure dubbed BASILICA, which Jaffar Khan, BMBCh (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD), and colleagues describe in a study also appearing online today ahead of print in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The novel technique is based on the LAMPOON procedure and involves a catheter-directed electrified guidewire that traverses and lacerates the aortic leaflet before TAVR is performed.

Khan and colleagues tested BASILICA first in five pigs and then on a compassionate use basis in seven patients from three institutions at high or prohibitive risk for surgery and at high risk of coronary obstruction with TAVR (six had failed bioprosthetic aortic valves and one had native aortic stenosis).

The procedure was successful in all patients, and no patient required hemodynamic support during the 8 to 30 minutes between laceration and valve deployment or after TAVR. Also, there was no evidence of coronary obstruction within 30 days after the procedure, and no patient had more than mild paravalvular leak.

As for complications, one patient reported transient sinus bradycardia requiring temporary transvenous pacing, but all patients survived through 30 days.

Latib, who also wrote the editorial that accompanies this study along with Matteo Pagnesi, MD (San Raffaele Scientific Institute), called the BASILICA technique “really ingenious,” and said that the timing of its publication was perfect in that “we highlight with my paper a potential complication and with the BASILICA, we have a potential solution.”

If you can't identify the risk, then you can't apply the technique. Tamim Nazif

Right now, if operators can identify a patient at risk for coronary obstruction, they have the option of using what is called chimney or snorkel stenting in which long stents are placed in the coronary artery and protrude into the aorta. While this “may work and they may be an acceptable option in say a really inoperable patient, in patients who have a longer life expectancy, I'm not convinced it's the most elegant option because we don't know long-term what is going to happen,” Latib said.

Commenting to TCTMD, Khan acknowledged that BASILICA is “not an entirely straightforward procedure,” and only recommended that physicians who are fluent in transcatheter electrosurgery techniques be trained in it. He said he has proctored the technique to operators at eight US and European institutions so far, and his team is starting a prospective early feasibility trial of 30 patients with initial results expected in 2019.

Going forward, he said he thinks there will be a lot of potential for BASILICA among patients with TAVR valves that begin to fail and require valve-in-valve procedures. “They are going to start to come back, and when they do I think this will be quite an important technique to help treat those patients,” Khan predicted.

But identifying which patients should even be considered for BASILICA is going to remain a challenge, according to Nazif. “In order to use it, one first needs to predict the risk for the coronary occlusion, and as shown in [the manuscript by Jabbour et al], the predictors are not so well developed,” he said. “If you can't identify the risk, then you can't apply the technique.”

Photo Credit: Giuseppe Tarantini (Padova, Italy) and Richard Jabbour. Used with permission.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Jabbour RJ, Tanaka A, Finkelstein A, et al. Delayed coronary obstruction after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1513-1524.

Kleiman NS. Delayed coronary obstruction after TAVR: a call for vigilance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1525-1527.

Khan JM, Dvir D, Greenbaum AB, et al. Transcatheter laceration of aortic leaflets to prevent coronary obstruction during transcatheter aortic valve replacement: concept to first-in-human. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Latib A, Pagnesi M. Tearing down the risk for coronary obstruction with transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2018;11:690-692.

Disclosures

- Latib reports serving on the advisory board of and as a consultant to Medtronic, receiving speaking honoraria from Abbott Vascular, and receiving research grants from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences.

- Kleiman reports receiving grant support for clinical trials from and providing educational services for Medtronic.

- Nazif reports serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic.

- Jabbour, Khan, and Pagnesi report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments