Encouraging Results Seen for TAVR in Failed Surgical or TAVR Valves

TAVR in SAVR was durable through 5 years, and TAVR in TAVR was safe and effective through 1 year.

TAVR is a safe and effective treatment option for failing aortic bioprostheses—be they surgical valves or prior transcatheter valves, registry studies presented during the virtual TCT Connect 2020 meeting show.

Five-year follow-up in the PARTNER 2 valve-in-valve (ViV) registries shows that using TAVR to correct degenerated surgical bioprostheses in patients at high to extreme risk provides outcomes similar to those seen with native-valve TAVR in intermediate-risk patients, with sustained improvements in valve hemodynamics, functional status, and quality of life, Rebecca Hahn, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), reported.

And 1-year results from the international TRANSIT registry, presented by Luca Testa, MD, PhD (San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy), showed that repeat TAVR in patients with failing transcatheter valves was safe and effective.

At a press briefing, Hahn said these types of data are “changing our algorithm for how we initially make decisions in our patients,” noting that the age at which patients are undergoing aortic valve replacement is getting lower over time. “Now we know that we can salvage those bioprosthetic valve failures with a transcatheter procedure that is relatively safe and has good outcomes, and now we’ve got outcomes out to 5 years with the second-generation valve, not even the third-generation valve,” she said.

For degenerated transcatheter valves, Hahn continued, “that algorithm is kind of the same. We know that if we have a choice between a TAVR and a surgical valve that we can actually salvage a TAVR with another TAVR, and that may end up changing the early decision-making process in those patients.”

PARTNER 2 ViV

Valve-in-valve TAVR outcomes have previously been shown to be acceptable through 3 years of follow-up, but longer-term results have been lacking, Hahn said. The 5-year results she presented at TCT Connect were based on 365 patients (mean age 79; 64% men) enrolled in two nested ViV registries of the PARTNER 2 trial. The patients had high or extreme surgical risk (mean STS score 9.1%) and symptomatic severe dysfunction of surgical bioprostheses larger than 21 mm, which made them suitable for treatment with a 23- or 26-mm Sapien XT valve (Edwards Lifesciences).

At 5 years, the all-cause mortality rate was 50.6%, lower than the 73.0% rate among inoperable patients treated with native-valve TAVR (P < 0.0001) in cohort B of the PARTNER 2 trial. Risk was numerically higher but not significantly different compared with intermediate-risk patients undergoing native-valve TAVR in cohort A of the PARTNER 2 trial (45.9%; P = 0.06).

Early improvements in mean gradients, Doppler velocity index, and total aortic regurgitation were sustained out to 5 years in survivors. At the end of follow-up, the rate of hemodynamic valve deterioration related to structural valve degeneration was 5.9%, of bioprosthetic valve failure was 4.7%, and of bioprosthetic valve failure related to SVD 2.3%. Risks were similar compared with intermediate-risk patients undergoing native-valve TAVR, Hahn reported.

TRANSIT

Introducing his presentation, Testa said that when a transcatheter valve degenerates, a second TAVR “seems an obvious and intriguing option considering that the surgical approach has been already rejected. However, its outcome is not yet fully elucidated.”

The TRANSIT registry, involving 22 centers in Europe, four in North America, and one each in South America and the Middle East, started analyzing data in January 2020 to assess the safety and efficacy of TAVR for the treatment of failed TAVR valves over the last 12 years. Out of about 40,000 TAVR procedures performed since 2008, researchers identified 172 cases of TAVR in TAVR, with a mean time between procedures ranging from about 1 to 3-and-a-half years across valve types. The mode of failure was mainly regurgitation in 97, mainly stenosis in 57, and mixed in 18.

The second bioprosthesis was successfully implanted in all patients, although VARC-2 device success rate was 79%, with 14% of patients having residual gradient and 7% regurgitation.

In the hospital, major vascular complications occurred in 2.3% of patients. A new pacemaker was required in 4.1%, and 3.5% had new-onset A-fib. The rate of acute kidney injury was 7.0%.

At 1 year, rates of overall and CV mortality were low at 10% and 5.8%, respectively, Testa reported. Rates were low for other adverse outcomes, including hospitalization for heart failure (11%), stroke (3.5%), valve thrombosis (1.4%), and MI (1.2%). Only 12.8% of patients were in NYHA class III or IV. There were no cases of valve endocarditis.

“The expanding adoption of transcatheter aortic valve replacement [in] relatively young and low-risk patients will conceivably result in an increasing number of patients with a degenerated bioprosthesis,” Testa said. “These patients may be safely and successfully treated by means of a second transcatheter procedure.”

He pointed out that these results were obtained with earlier generations of TAVR valves. “We need to remember that what we are doing is looking backwards because [the] current generation of TAVR platforms nowadays are better as compared to those we were implanting 5 or 6 years ago,” he said. “So in other words, to those patients already treated, we have a safe and effective procedure but . . . in the future we can actually change the paradigm or treatment of aortic stenosis in relatively younger and lower-risk patients. We can do that safely and successfully.”

Some words of caution arose during the panel discussion after his presentation, however. Moderator Michael Borger, MD, PhD (Leipzig Heart Center, Germany), said, “I’m not quite as optimistic about the results as you seem to be,” pointing to the 30-day mortality rate of 7% and the procedural success rate of 79%, lower than in other studies.

Similarly, Vinayak Bapat, MD (Minneapolis Heart Institute, MN), said of the results, “I’m less optimistic because of this.” He cited the fact that these patients, all of whom had an initially successful TAVR, had to return for another procedure within an average of about 2 to 4 years. If an operator were to put in another transcatheter valve, he asked, would it last more than 2 years?

Testa responded by noting that all of these patients had been evaluated by a heart team and it was determined that TAVR was the best option. “Would you suggest surgery for that patient? I would not.”

To that, Borger said, “There’s something about them that they’re not tolerating the valve well, and I’m not sure it’s the best strategy to go ahead and put a second valve in.”

The Patient’s ‘Valve Journey’

Commenting for TCTMD, Amar Krishnaswamy, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), said the most important part of the PARTNER 2 ViV findings is that “the durability of the valve-in-valve prosthetic appears to be stable. This is a time when in both native-valve TAVR and valve-in valve TAVR everyone is really interested in what the durability of the TAVR prosthetic is and to see that out at 5 years the mean gradient and the effective orifice area are stable is I think quite encouraging.”

The hemodynamic results of ViV TAVR might be even better now, he said, because operators know more about how to optimize the ViV result with aggressive high-pressure postdilation and surgical valve fracture, which wasn’t routinely done when the PARTNER 2 registries were enrolling.

Another consideration, Krishnaswamy said, is that over time during the TAVR era, patients treated surgically are receiving larger bioprostheses. “My hope as we move forward is that valve-in-valve TAVR is in fact even a better strategy than it has been in years past because it’s always better to put a TAVR inside a larger surgical valve.” Surgeons should be mindful of the potential need for a ViV TAVR in the future, he added. “In addition to optimizing surgical valve size, they should consider use of valves that are known to be more amenable to ViV TAVR.”

It behooves us as operators to really think about the patient’s valve journey in the future and whether a specific TAVR at the index valve procedure may be better suited to a future TAVR in TAVR. Amar Krishnaswamy

As for TAVR in failing transcatheter valves, Krishnaswamy said this will “become a more important mode of treatment for our patients as those patients that we treated 7 and 10 years ago with TAVR are now going to be coming back with degenerated TAVR valves. And I think that there’s every reason to believe that it’s a safe and effective treatment strategy based on the data that’s presented here by Testa as well as prior data that’s been presented.”

What’s critical to understand, he said, is that the outcomes of this procedure are dependent on how the initial TAVR was performed. Previous research has shown that patients who first received a smaller valve—23 mm or less—had a worse hemodynamic result with a repeat TAVR. “That’s an important thing for people to realize, especially as we’re treating younger and lower-risk patients with TAVR. If we are going to be putting in a small TAVR in someone who is at a low risk, we really need to consider what that means in the future when we may be only then able to put in a small TAVR in TAVR, and that might not be an optimal hemodynamic result,” Krishnaswamy advised.

Operators also need to consider risks of coronary obstruction when selecting a bioprosthesis, Krishnaswamy said. “It behooves us as operators to really think about the patient’s valve journey in the future and whether a specific TAVR at the index valve procedure may be better suited to a future TAVR in TAVR,” particularly as the procedure moves into patients with longer expected life spans. “I am confident that a future TAVR in TAVR will be a safe and effective strategy as long as I know that I can optimize their current TAVR with a large prosthetic device and without concerns for coronary obstruction in the future when I’m going to consider a TAVR in TAVR. And if I can’t confidently state both of those things in a patient who is young and at low risk, it may be that the best advice is to pursue an index surgery with a valve-in-valve TAVR in the future.”

Note: Hahn is a faculty member of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD.

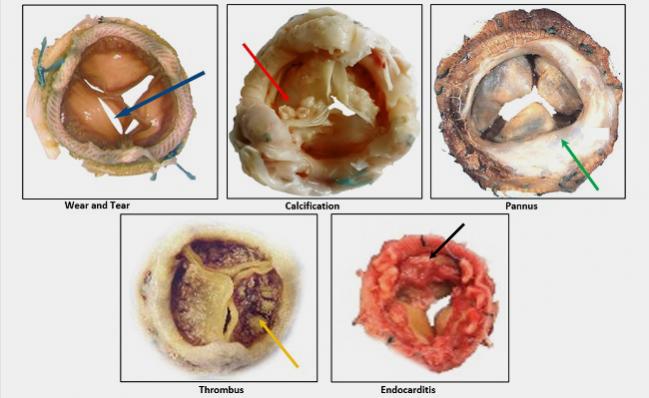

Photo credit: Rebecca Hahn

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Hahn RT. Five-year follow-up from the aortic valve-in-valve registries. Presented at: TCT 2020. October 17, 2020.

Testa L. TRANSIT: treatment of failed TAVR with TAVR. Presented at: TCT 2020. October 17, 2020.

Disclosures

- Hahn reports receiving fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic Navigate, and W.L. Gore & Associates, as well as having equity/stock(s)/options in Navigate.

- Testa and Krishnaswamy report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments