LDL Apheresis Potentially a ‘Head Start’ to Conventional Lipid-Lowering Methods Post-PCI in ACS: PREMIER

Outcomes studies are still warranted in more generalizable, non-FH populations, but the procedure is safe, a study author says.

Subhash Banerjee, MD (VA North Texas Health Care System & UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas), who presented the results of the PREMIER trial in a featured clinical research session at the annual meeting of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), urged caution at interpreting the results of this small study, especially since its statistical power was based on the effect of LDL apheresis in a population of FH patients.

“We want to be conservative for drawing conclusions and we want to emphasize the safety endpoint,” he said. “I think further studies are needed to derive clinical benefit from this therapy going forward, and that would be the scope of our work starting now in the next few years.”

Nonetheless, given that the mean baseline LDL in the study was 113 mg/dL, Banerjee told TCTMD that it “shows that this therapy can be safely inducted into the care plan for those patients who don't have astronomically high LDL levels.”

Safety Assured

Generally used in FH patients up until now, LDL apheresis is a procedure by which blood is filtered extracorporeally to remove lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B. Prior studies have shown that while the process strains out LDL cholesterol, it also lowers lipoprotein(a) and PCSK9 levels as well. The system used in this US Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption trial was the Liposorber (Kaneka), which uses dextrose sulfate cellulose beads to filter peripheral blood through an IV.

For PREMIER, Banerjee and colleagues first tested the safety of the Liposorber system among 329 NSTEMI and unstable angina patients with LDL 70 mg/dL or greater while on atorvastatin who were undergoing PCI at four Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. With the FDA’s permission, they then randomized 160 of these patients to moderate-to-intense statin therapy with or without a single LDL apheresis procedure within 72 hours of PCI. All randomized patients received follow-up with IVUS at 90 days.

Overall, LDL apheresis lowered LDL by 56% in the study arm, substantially greater than the 17% reduction observed in the statin only cohort.

In both the intention-to-treat and as-observed analyses, there were no differences between the study arms regarding the primary effectiveness endpoint of percent change in coronary plaque volume at 90 days. Banerjee highlighted that the confidence interval for the LDL apheresis arms in both analyses was entirely below zero, indicating potential for the treatment.

Percent Change in Coronary Plaque Volume at 90 Days

|

|

LDL Apheresis |

Statins Alone |

P Value |

||

|

% Change |

95% CI |

% Change |

95% CI |

||

|

ITT |

-4.81 |

-8.91 to -0.71 |

2.31 |

-3.98 to 8.61 |

0.0611 |

|

As-Observed |

-5.46 |

-10.11 to -0.81 |

2.59 |

-4.46 to 9.64 |

0.0597 |

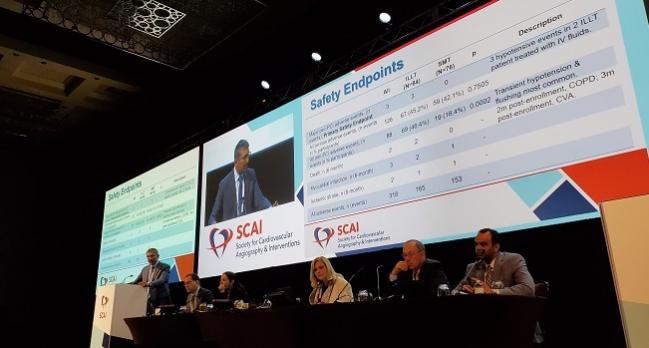

Major adverse peri-PCI events (primary safety endpoint) were rare, with only two patients in the LDL apheresis cohort reporting three hypotensive events. The rate of all peri-PCI adverse events was higher in those who received LDL apheresis compared with those on statins alone (46.4% vs 18.4%; P = 0.0002), with most of these events being transient hypotension from prior exposure to ACE-inhibitors, Banerjee said. Two patients in the study group died—one from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at 2 months and one from a stroke at 4 months.

Though the mean length of stay was a day longer in the LDL apheresis arm (2.54 vs 1.75 days; P = 0.0037), this amount of additional time in the hospital is “still acceptable for current practice indicators,” according to Banerjee.

Notably, patients were excluded from PREMIER if their triglycerides were > 500 mg/dL, they were undergoing complex PCI, or had poor renal function.

Synergistic Therapy?

Asked during a press conference whether he could see LDL apheresis being chosen over a PCSK9 inhibitor down the line, Banerjee said the two could be used in synergy. “[LDL apheresis] is done acutely in the peri-infarct or peri-ACS patient before the patient is discharged, so it does not preclude continued therapies that would be included in the patient's regimen, [whether that’s] continued statin therapy or, in those who are unresponsive or less responsive to statins, PCSK9 therapies,” he said. “I don’t view this as an ‘if’ or an ‘or’ question but probably an ‘and’ question, where if the safety and the clinical efficacy of this therapy is proven, it can easily be implemented.”

During the main session, co-moderator Daniel M. Kolansky, MD (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), called the concept of LDL apheresis in ACS patients undergoing PCI “very thought-provoking.”

Panelist Theodore A. Bass, MD (University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville), noted that “there seems to be a catch-up in terms of LDL levels and is fairly robust and occurred fairly soon.” He asked: is plaque regression indeed occurring, and if so, what are the mechanisms behind this treatment?

“By seeing a rebound for LDL by the FH populations, I would urge you to consider that in non-FH populations, where there is no deficiency in the number of LDL receptors, a lowering of acute LDL can cause a rebound uptake in the LDL-receptor numbers,” Banerjee replied. Secondly, “LDL apheresis also removes PCSK9, so I think the effect seen in non-FH patients may be tangentially different from those seen in FH patients. And hence there could be a potentially longer effect than expected, because otherwise LDL would be manufactured in hours.”

This is why Banerjee said he would prefer to use LDL apheresis just once in patients as a “as a head start and then use conventional lipid-lowering therapies. . . . The early regression or the early clinical effect in LDL might be beneficial.”

Session co-moderator Sara Martinez, MD, PhD (Providence Medical Group, Olympia, WA), asked about the cost difference of potentially just giving these patients a PCSK9 inhibitor instead of LDL apheresis.

“I would have to do the math, but I can tell you that on my notebook it is mammoth,” Banerjee responded, adding that currently for FH patients LDL apheresis costs about $2,000 and is completely reimbursed.

Ultimately, it is imperative that an outcomes trial in a non-FH patient population be conducted before this therapy can be considered in this subgroup, he stressed.

PREMIER “does show that there is effective regression of plaque, but I do believe that clinical benefit of this therapy longer term, in larger group of patients definitely needs to be studied,” Banerjee said, citing an additional limitation of the study: it was conducted at VA centers and therefore 99% of recruited participants were men. “I do believe very strongly that more generalizable conclusions can be drawn if it is done in non-VA centers with a more robust recruitment and enrollment of participants,” he advised.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Banerjee S. Plaque regression and endothelial progenitor cell mobilization with intensive lipid elimination regimen (PREMIER). Presented at: SCAI 2019. May 21, 2019. Las Vegas, NV.

Disclosures

- The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Banerjee reports serving as a proctor for Medtronic, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Aralez; as a consultant for AstraZeneca; and as a principal investigator for a research study for Boston Scientific and Aralez.

Comments