LoDoCo2: Colchicine Protective in Large RCT of Chronic Coronary Disease

On top of last year’s COLCOT results, the new findings add fuel to the inflammatory hypothesis, researchers say.

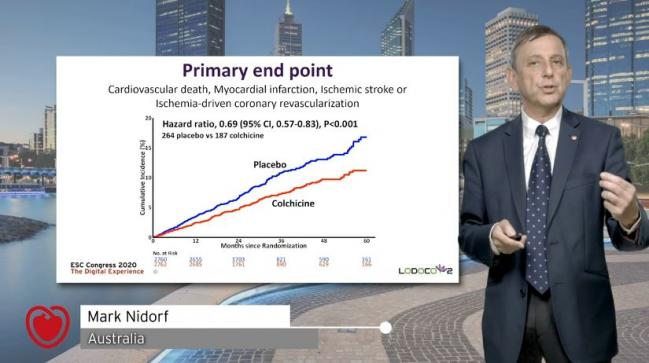

(UPDATED) Colchicine taken at a daily dose of 0.5 mg safely reduces cardiovascular events among patients with chronic coronary disease, according to data from the placebo-controlled randomized LoDoCo2 trial.

“LoDoCo2 provides strong evidence to support repurposing colchicine for routine secondary prevention in patients with chronic coronary disease,” said Mark Nidorf, MD (GenesisCare Western Australia, Perth), in a press briefing. He presented the results virtually today in a Hot Line session of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2020.

LoDoCo2’s positive outcome—which sparked much discussion among the session’s participants and the ESC “attendees,” who posted comments and questions via the live chat—builds on an evolving body of evidence that increasingly supports, after some early misses, the inflammatory hypothesis in cardiovascular disease. The question now is how it will roll out in practice.

The first LoDoCo trial, published in 2013, also showed promise for colchicine in chronic disease but was small and didn’t involve a placebo. Then, in 2017, CANTOS renewed excitement by showing a modest reduction in major CV events with the human monoclonal antibody canakinumab (Ilaris) in stable CAD patients. Yet hopes began to fade when the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis, decided not to pursue a CV indication. A year later, CIRT failed to show CV benefit with another anti-inflammatory, methotrexate.

Then, in late 2019, came fresh interest thanks to COLCOT, with more than 4,700 patients who had recently experienced an MI—LoDoCo2 closes the loop by focusing, yet again, on chronic coronary disease. Its findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

We now have a second large cardiovascular outcomes trial after COLCOT, which was presented last year, that shows the benefits of an anti-inflammatory drug, colchicine, in a low dose that is widely available and could be prescribed to our patients. Arend Mosterd

Arend Mosterd, MD, PhD (Meander Medical Center, Amersfoort, the Netherlands), a LoDoCo2 investigator, elaborated to the media on why the data are persuasive. “We now have a second large cardiovascular outcomes trial after COLCOT, which was presented last year, that shows the benefits of an anti-inflammatory drug, colchicine, in a low dose that is widely available and could be prescribed to our patients,” he said, noting that it’s already being prescribed for pericarditis.

Inflammation, Mosterd said, is a “new pillar in the treatment of coronary disease.” Colchicine should play a role in medical therapy, he asserted. “Of course, this remains to be determined by the medical public. We think we have made our point in combination with . . . the COLCOT trial.”

Richard J. Kovacs, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis), immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology, said he views this “not just the story of colchicine but the story of inflammation.

“Can we intervene on inflammation and see favorable cardiovascular outcomes? I think that is another important piece in that puzzle,” he commented to TCTMD. Whether this will lead to a change in guidelines and practice isn’t yet certain, said Kovacs.

Late last year, the COLCHICINE-PCI trial showed that colchicine, given orally prior to PCI in an all-comers population, does not reduce procedure-related myocardial injury but does appear to attenuate the inflammatory response. CLEAR-SYNERGY, now underway, is looking at the acute, peri-STEMI period.

LoDoCo2

Enrolling from Australia and the Netherlands, LoDoCo2 investigators studied 5,522 participants who had chronic CAD (any evidence on invasive or CT angiography or a coronary artery calcium score of ≥ 400 Agatston units) and had been clinically stable for at least 6 months, randomizing them to colchicine 0.5 mg or placebo. Mean age was 66 years, and 15.3% were women. Fully 84.4% had a history of ACS, though for most their event happened more than 2 years prior. At baseline, 99.7% were taking an antiplatelet or anticoagulant, 96.6% a lipid-lowering agent, 62.1% a beta-blocker, and 71.7% a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system inhibitor.

Eventually 10.5% of individuals in each group prematurely stopped taking their assigned regimen.

Still, over a median follow-up duration of 28.6 months, primary endpoint events (CV death, nonprocedural MI, ischemic stroke, or ischemia-driven coronary revascularization) were decreased with colchicine (6.8%) compared with placebo (9.6%). These rates amounted to an incidence of 2.5 events per 100-person years for colchicine and 3.6 events per 100 person-years for placebo (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.57-0.83). Results were consistent across subgroups.

Various other secondary composites, as well as ischemia-driven revascularization and spontaneous MI individually, also were less frequent with colchicine. Noncardiovascular death was slightly but significantly higher with colchicine than with placebo, at 0.7 versus 0.5 events per 100 person-years (HR 1.51; 95%CI 0.99-2.31). Cancer diagnoses, though, did not differ between the two study arms. Nor did hospitalizations for infection, pneumonia, or a gastrointestinal reason. In terms of side effects, colchicine was associated significantly with less gout (1.4% vs 3.4%) but more myalgia (21.2% vs 18.5%).

The Unknowns

There were some limitations to LoDoCo2, as the researchers acknowledge in their paper. The study didn’t collect blood pressure or lipid levels at baseline or during the trial. Nor were C-reactive protein and other signs of inflammation routinely assessed, meaning that “we cannot explore the effects of treatment according to inflammatory state at baseline,” they write.

Another caveat, they say, is the low proportion of women—something Kovacs also drew attention to. “The percentage of women in the trial was lower than would be expected,” the investigators note, “given the percentage of women with chronic coronary disease in the general population.”

[It's] not just the story of colchicine but the story of inflammation. Richard Kovacs

TCTMD, in an online press conference, asked how this sex imbalance came about and how it should affect the study’s interpretation.

Jan Hein Cornel, MD (Northwest Clinics, Alkmaar, the Netherlands), agreed this was a concern but didn’t elaborate on how it affects LoDoCo2’s generalizability. “We recruit patients from our daily practices all across the Netherlands and Australia, and it happens to be that the overwhelming amount of people are male,” he said, adding, “We should go further and dedicate further research exactly towards [women] because it’s an understudied population. So it’s an important question.”

Clarity on who should receive the drug, how, and to what end are all important questions. Kovacs emphasized that writing committees for guidelines “will want to point to a very particular patient population. Now we have studies in recent post-MI and then we have studies in patients with chronic coronary disease, but what I’m still not clear on is [for] which patients and when we will add on colchicine.”

Also pertinent is the question of how female patients will do on this drug, Kovacs said, noting that their underenrollment “was a big disappointment. Fifteen percent women in the study—I don’t know how that happened.”

Data Spark Dialogue

Discussant Massimo Imazio, MD (University of Turin, Italy), in the live ESC session, agreed that LoDoCo2 “provides convincing evidence that colchicine is safe and efficacious for secondary prevention in chronic coronary syndromes—of course, if tolerated.”

Experience in patients with pericardial disease shows that, in this regard, it’s important to use low doses and not administer a loading dose, Imazio advised. He pointed out that in the original LoDoCo trial, about 10% of patients on colchicine had “gastrointestinal intolerance.” LoDoCo2 addressed this “very wisely” with an open-label run-in period, he said, only afterward randomizing patients who were stable, without side effects, adherent to the regimen, and still willing to enroll. Of the 6,528 patients who started the run-in period, 15.4% weren’t randomized. For 6.7%, the reason was GI upset.

“We also should be aware of potential side effects of the drug and interactions—for patients with coronary syndromes [there’s] a very important potential interaction with statins (eg statins)—and so monitoring . . . is indicated, especially blood cell count, transaminases, [and creatine kinase],” said Imazio.

Overall, the news is good, he concluded. “I think we have growing evidence nowadays supporting colchicine on top of standard medical therapy to reduce major cardiovascular events in patients with chronic but also acute coronary syndromes” by 23-31%.

[LoDoCo2] provides convincing evidence that colchicine is safe and efficacious for secondary prevention in chronic coronary syndromes—of course, if tolerated. Massimo Imazio

Filippo Crea, MD (Catholic University, Rome, Italy), who chaired the Hot Line session, credited Imazio for first drawing attention to colchicine’s role in treating pericarditis.

Crea asked Nidorf one question posed by a member of the online audience—why were there regional differences? As noted in the NEJM paper, colchine’s effect on the “primary endpoint was directionally consistent but appeared to be quantitatively larger in Austrlia than in the Netherlands.”

This disparity “was a bit unexpected,” Nidorf replied, “because there were more similarities than differences between our populations, other than a few factors such as smoking. That said, we believe the totality of the data speak to its strengths and we believe the differences we saw were most likely to the play of chance.” Predictors of outcome in LoDoCo2 were related to age and diabetes, he added.

For his part, Crea observed that unlike in CANTOS, where there was a signal suggesting higher risk of infection, this wasn’t seen in LoDoCo2. Nidorf, who noted that this risk also was hinted at in COLCOT, said its absence here was reassuring.

That question, however, inspired him to mention one additional concern, specifically that the antibiotic clarithromycin “interacts very unfavorably with statins but also [colchicine],” said Nidorf, “And if we are to use this drug widely, clinicians will need to learn what . . . drugs to avoid. That’s an important teaching point.”

Stephan Achenbach, MD (Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen, Germany), also a session chair, agreed. “The practical issues of this therapy in all of our patients with coronary disease, of course, we’ll all have to learn about.”

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Nidorf reports grants from the National Health Medical Research Council of Australia and the Sir Charles Gairdner Research Advisory Committee as well as nonfinancial support from Aspen during the conduct of this study.

- Cornel reports grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Netherlands Heart Foundation, the Withering Foundation the Netherlands, and from a consortium of Teva, Diphar, and Tiofarma in the Netherlands during the conduct of the study as well as personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, the Perfusion study group, and IQVIA outside the submitted work.

- Mosterd reports grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Netherlands Heart Foundation, the Withering Foundation the Netherlands, and from a consortium of Teva, Diphar, and Tiofarma in the Netherlands during the conduct of the study as well as grants from Novartis and personal fees from Amarin, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, and Pfizer outside the submitted work.

- Kovacs reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments