Mixed Results for Beta-blockers in Post-MI Patients With Preserved EF

(UPDATED) One trial showed beta-blockers helped after MI, and the other did not. Researchers still say there is a coherent message.

MADRID, Spain—Two randomized, controlled trials testing beta-blockers in post-MI patients without heart failure or impaired left ventricular ejection fraction added a bit of confusion to a field trying to understand the benefits of this long-used therapy.

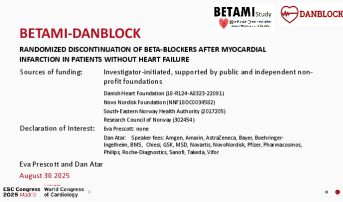

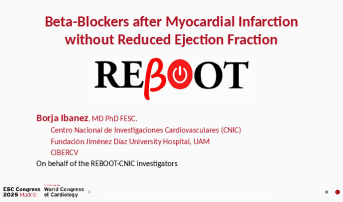

The trials, both presented today during a Hot Line session at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2025, yielded opposing results: REBOOT-CNIC showed there was no clinical benefit of beta-blocker therapy when used in post-MI patients with an ejection fraction greater than 40%, while BETAMI-DANBLOCK found that the drugs lowered the risk of death or MACE in post-MI patients with LVEF ≥ 40%.

For investigators, though, the devil is in the details. In fact, both research groups say a coherent message emerged from the two trials, pointing to subgroup analyses and an updated meta-analysis that found a benefit of beta-blockers in post-MI patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction, defined as 40% to 49%.

“We can see that these results are actually not very different,” Eva Prescott, MD, DMSc (Bispebjerg Frederiksberg University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark), co-principal investigator of BETAMI-DANBLOCK, told TCTMD. “When we look at [our trial], we could also see a trend, not a significant [finding], where patients with low ejection fraction seemed to have a benefit.”

In REBOOT-CNIC, which was led by Borja Ibáñez, MD, PhD (Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III/Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital, Madrid), there was no benefit overall with beta-blocker therapy, but there was a trend toward better outcomes in patients with mildly reduced LVEF (< 50%).

The subgroup analyses were backed by a meta-analysis that confirmed a lower risk of all-cause mortality, MI, or heart failure (HF) in post-MI patients with mildly reduced LVEF.

“These results have the potential to change medical practice and impact millions of people having a myocardial infarction, where currently most of them are discharged with a beta-blocker,” Ibáñez said. Now, instead of reflexively prescribing a beta-blocker to all post-MI patients, a more personalized approach that accounts for LVEF will home in on those who will benefit from treatment, he told TCTMD.

“We use ejection fraction thresholds for implanting defibrillators, for giving heart failure therapy, and for SGLT2 inhibitors,” Ibáñez told TCTMD, adding that beta-blocker use after MI should be no different.

Both REBOOT-CNIC and BETAMI-DANBLOCK were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, while the meta-analysis was published in the Lancet.

Guidelines Call for Beta-blockers After ACS

In the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of ACS, starting beta-blockers within 24 hours is recommended to reduce the risk of ventricular arrythmias and reinfarction (class 1 recommendation, level of evidence A). In Europe, guidelines say the routine use of beta-blockers should be considered for all ACS patients regardless of LVEF (class 2a recommendation, level of evidence B).

However, the supporting evidence is based on clinical trials performed before the advent of routine reperfusion, including PCI with drug-eluting stents, and contemporary guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). As such, the long-term use of beta-blocker therapy after MI has been challenged in recent years. The REDUCE-AMI trial, published in 2024, found that long-term beta-blocker therapy in patients with acute MI and preserved ejection fraction did not lower the risk of death or recurrent MI.

These results have the potential to change medical practice and impact millions of people having a myocardial infarction. Borja Ibáñez

In the US guidelines for the treatment of chronic coronary syndromes, long-term use of beta-blockers is no longer recommended for patients without MI in the past year, without impaired LVEF, or without another primary indication for beta-blocker therapy, such as angina, arrhythmias, or hypertension. In patients who’ve had an MI in the past year, physicians are advised to reassess the indication for long-term use (> 1 year) for reducing MACE (class 2b recommendation).

“Patients that have a weakened heart, which is an ejection fraction below 40%, clearly benefit from beta-blockers, but the benefit in those patients with an ejection fraction above 40% is less clear,” said Ibáñez .

REBOOT-CNIC, an open-label trial, included 8,438 patients (mean age 61 years; 19.3% women) with ACS and LVEF > 40% from 109 centers in Spain and Italy randomized to beta-blockers or no beta-blockers.

After median follow-up of 3.7 years, there was no significant difference in the risk of death from any cause, reinfarction, or hospitalization for HF in patients treated with beta-blockers versus those who weren’t (22.5% vs 21.7%; HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.89-1.22). There were no significant differences on any of the secondary outcomes, including all-cause mortality, reinfarction, or HF hospitalization analyzed alone.

During his presentation, Ibáñez highlighted subgroups stratified by sex and LVEF. In those with LVEF less than 50%, there was a trend toward a 25% lower risk of the study’s primary endpoint, with a higher risk seen in those with LVEF 50% or greater. Women also appeared to do worse with beta-blockers (HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.04-2.03). When researchers delved further, the higher risk was seen in women with normal LVEF, but not in those with mildly reduced LVEF.

They all point in this direction—that there is a benefit in the subgroup with ejection fraction below 50%. Eva Prescott

The BETAMI-DANBLOCK trial combined two ongoing studies, one from Norway and the other from Denmark, that had nearly identical designs and similar inclusion/exclusion criteria. In total, 5,574 patients (mean age 63 years; 20.8% women) with MI in the past 7 or 14 days and with an LVEF of at least 40% were included in the combined study. The BETAMI trial included only patients who underwent coronary revascularization, but that was not required in DANBLOCK.

After a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the composite endpoint of death from any cause, MI, unplanned revascularization, ischemic stroke, HF, or ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 14.2% of those treated with beta-blockers and 16.3% of those who weren’t (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.75-0.98). The benefit was mainly driven by a lower risk of MI (HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.59-0.92), although most endpoints, except for ischemic stroke, favored treatment.

In the subgroup analysis, the benefit of beta-blockers appeared slightly larger in patients with mildly reduced LVEF (40% to 49%) versus those with normal ejection fractions.

All investigators participated in a patient-level meta-analysis, with data from REBOOT-CNIC, BETAMI, DANBLOCK, and CAPITAL-RCT, a Japanese trial evaluating the long-term use of carvedilol in STEMI patients treated with PCI. The analysis included 1,885 patients with mildly reduced LVEF and no history or signs of HF.

Overall, the primary composite endpoint of all-cause death, new MI, or HF was reduced by 25% with beta-blocker therapy, a significant difference when compared with no beta-blockers.

“There’s no heterogeneity between the trials,” said Prescott. “They all point in this direction—that there is a benefit in the subgroup with ejection fraction below 50%.”

Interpreting the Findings

ACC President Christopher Kramer, MD (UVAHealth, Charlottesville, VA), said the lower the ejection fraction, the greater the benefit from beta-blockers. In that way, REBOOT-CNIC and BETAMI-DANBLOCK aren’t completely at odds. The meta-analysis, as well as the subgroup analysis, suggests that there is a benefit for those with LVEF in the 40% to 49% range.

“When you have [left ventricular] dysfunction, there are benefits in all ranges of ejection fraction,” he told TCTMD. While physicians will put nearly everyone on a beta-blocker after MI, these new data are challenging that treatment plan. Unless LVEF is impaired, “maybe you don’t need it,” he said.

If the infarction is small, and the heart works well, it looks like beta-blockers are not helpful. Filippo Crea

Filippo Crea, MD, PhD (Catholic University, Rome, Italy), who chaired a Hot Line press conference, echoed that sentiment.

“If the infarction is small, and the heart works well, it looks like beta-blockers are not helpful,” he said. “In patients where the infarction is small, but some damage of the heart is present—an ejection fraction between 40% and 50%—then, for the first time, we have some convincing evidence that beta-blockers help also in this patient subset.”

Sripal Bangalore, MD (NYU Langone Health, New York, NY), who has previously questioned the use of beta-blockers in post-MI patients, said it is an impressive feat for multiple trials to test the efficacy of beta-blocker therapy in this setting. These are generic medications, and trialists undertook the studies with no industry support.

However, he is not fully sold that there is a benefit of beta-blockers in post-MI patients with preserved or mildly reduced LVEF.

Of the three randomized trials performed to date, two—REDUCE-AMI and REBOOT-CNIC—found no benefit of therapy. In the lone positive study, BETAMI-DANBLOCK, there was a 2.1% absolute reduction in the primary endpoint over 3.5 years, translating to a low 0.6% absolute reduction per year, he noted. All told, 48 patients would need to be treated with beta-blockers to prevent one clinical event over 3.5 years, with no difference in the important endpoint of all-cause mortality.

There was a small absolute reduction in the risk of recurrent MI—less than 0.5% per year—suggesting that the “majority [of post-MI] patients do well regardless” of whether they receive a beta-blocker, said Bangalore.

Overall, event rates are low in all three trials, “attesting to the progress we have made with reperfusion and modern GDMT,” Bangalore told TCTMD. “Treatment decisions need to be individualized, but my read on the totality of the data is that the benefit is mediocre at best when compared with [use in] [heart failure with reduced ejection fraction].”

Patients with mildly reduced LVEF, and those with symptoms, could possibly benefit from beta-blockers, but it would be up to physicians to personalize care, said Bangalore.

John Cleland, MD (University of Glasgow, Scotland), the discussant following the trial’s presentation, also agreed the data looks “pretty neutral” in those with LVEF ≥ 50%.

“I think that we should generally start people on full panoply of therapy in this vulnerable phase after myocardial infarction, but the patient should be reviewed 6 to 12 weeks later,” he said. In patients without LV dysfunction or another indication, “then there should be selective omission of the renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors and beta-blockers,” said Cleland. “There are many reasons why these should be continued, but there are probably no good reasons why they should be continued lifelong in many patients.”

Prescott acknowledged the relatively small absolute reduction in risk in BETAMI-DANBLOCK, but said “many trials nowadays have very small absolute effects.” Nonetheless, these can help inform patient-physician discussions around therapy, she said, adding that their group plans to evaluate quality-of-life measures and side effects to help better inform decisions.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Ibáñez B, Latini R, Rossello X, et al. Beta-blockers after myocardial infarction without reduced ejection. N Engl J Med. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Munkhaugen J, Kristensen AMD, Halvorsen S, et al. Beta-blockers after myocardial infarction without heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Rossello Lozano X, Prescott EIB, Kristensen AMD, et al. Beta-blockers after myocardial infarction with mildly reduced ejection fraction: an individual patient-data meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials. Lancet. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Ibáñez, Prescott, Kramer, Crea, and Bangalore report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments