More HF, Worse Long-term Outcomes in TAVI Patients Who Get Pacemakers

The researchers say longer monitoring of rhythm disturbances and consideration of biventricular pacing may be needed.

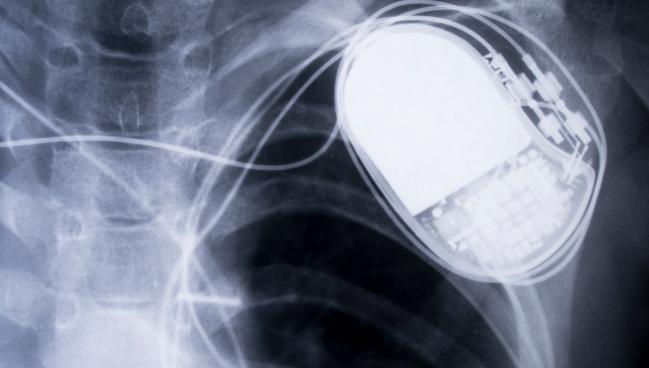

Some patients who require placement of a permanent pacemaker for conduction disturbances after TAVI have declines in heart function not seen after the procedure or in the early months thereafter, a systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

While many studies have assessed predictors of post-TAVI conduction abnormalities—and strategies to reduce the need for permanent pacemakers—little data exist on the short- and long-term outcomes of patients discharged with a pacemaker, lead study author Rahul Gupta, MD (Lehigh Valley Heart Institute, Allentown, PA), told TCTMD.

For the study, published in the August 22, 2022, issue of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, Gupta and colleagues analyzed data from 167,387 TAVI patients (mean age 80; 46% men) from 42 studies. In all, 25,581 patients required permanent pacemaker implantation. The mean baseline LVEF was 53% in the pacemaker group and 52% in the non-pacemaker group.

“What we found was that long-term heart failure, all-cause readmissions, as well as all-cause mortality was higher in the patients who received a pacemaker after TAVR,” he said. “But this effect was only seen after 1 year.” According to Gupta and colleagues, that finding suggests that long-term pacing through the right ventricle may lead to development of ventricular dyssynchrony.

Compared with patients not requiring a pacemaker after TAVI, those who did were more likely to have a heart failure readmission at 1 year (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.06-1.90) and at the longest available follow-up (OR 1.75; 95% CI: 1.43-2.15), which ranged from a minimum of 1 year to up to 5 years in the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Similarly, pacemaker patients saw higher all-cause readmission at 1 year (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.21-1.84), and higher all-cause mortality at both 1 year (OR 1.23; 95% CI: 1.05-1.45) and the longest available follow-up (OR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.00-1.53). Additionally, in a small number of studies that reported LVEF improvement after the procedure, patients without pacemakers had a higher degree of improvement than did those with pacemakers in nearly all of the studies. There were no long-term differences between the pacemaker and non-pacemaker groups in rates of MI, stroke, or atrial fibrillation.

Gupta said the data, limited though they are, suggest the need for more focus on patients with pacemakers after TAVI to better understand how to manage them, and gain insight into how and when pacing might start to cause problems.

“Often, we put in pacemakers after the procedure and then they get followed up at a different place, so we do not assess how much pacing they are actually getting and [how] the pacing is affecting them,” Gupta observed. “In our analysis, we did not find many studies reporting the effects of pacing on heart failure over a long term in these patients, so those data are needed.”

Gupta and colleagues also say the findings suggest the need to take a new look at how pacing is incorporated into care after TAVI, especially as the procedure expands to younger patients and those with complicated anatomy. One possibility is that extended rhythm monitoring might be helpful for some patients being considered for permanent pacemakers. The other is to look beyond traditional ventricular pacing.

“In those patients who really need a pacemaker and are at higher risk for having heart failure in the future, biventricular pacemakers should be considered,” Gupta added. “That is our hypothesis, and it needs to be studied further.”

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Gupta R, Mahajan S, Behnoush AH, et al. Short- and long-term clinical outcomes following permanent pacemaker insertion post-TAVR: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2022;15:1683-1692.

Disclosures

- Gupta reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments