MOST: Eptifibatide, Argatroban Don’t Improve on IV Thrombolysis Alone

It’s possible that other classes of antithrombotics may be worth adding to improve reperfusion, but that’s conjecture right now.

Adding argatroban or eptifibatide does not improve outcomes for patients receiving IV thrombolysis for an acute ischemic stroke, the phase III MOST trial shows.

Neither IV agent boosted 90-day functional outcomes compared with placebo, and while the treatments were mostly safe, there were signs that patients who received argatroban on top of IV thrombolysis had worse outcomes compared with placebo, reported Opeolu Adeoye, MD (Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO), and Andrew Barreto, MD (University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston), here at the International Stroke Conference.

“There doesn’t seem to be any benefit of adding a direct thrombin inhibitor, argatroban, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, eptifibatide, to [alteplase] or tenecteplase, whichever one of the thrombolytics that you use,” Barreto told TCTMD. That comes as a surprise, he added, in light of favorable signals observed in several phase II studies.

Importantly, there was no increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage—a feared complication when adding antithrombotics to thrombolytics—with either of the agents tested in MOST, Barreto said. “It doesn’t seem to increase the risk of bleeding. It just didn’t help with reducing stroke disability.”

The MOST Trial

IV thrombolysis alone opens only about 50% of occluded arteries, and up to one-third of the arteries that have been opened then reocclude acutely, which worsens outcomes, Adeoye said. Moreover, about half of patients with acute ischemic stroke who receive IV thrombolysis remain disabled 3 months later.

Research within the cardiology realm has shown that the addition of antithrombotics to thrombolysis can augment clot lysis, and possibly reperfusion, providing the rationale for testing a similar approach in the setting of acute ischemic stroke, Adeoye said.

Several phase II trials showed that combining either argatroban or eptifibatide with IV thrombolysis was safe and suggested that it might be beneficial. That laid the groundwork for the phase III MOST trial, which was conducted across 57 US sites participating in the National Institutes of Health StrokeNet.

The trial included patients with acute ischemic stroke who were treated with standard-of-care IV thrombolysis (alteplase or tenecteplase) within 3 hours of symptom onset, had an NIHSS score of 6 or higher, and could be treated with one of the study drugs no more than 75 minutes after the start of thrombolysis. Eligible patients also underwent endovascular therapy.

The plan was to include more than 1,200 patients, but the trial was stopped after 514 (median age about 68 years; 50% women) were enrolled based an assessment of futility by the data and safety monitoring board. At that point, 228 had received placebo, 227 eptifibatide (135 µg/kg bolus followed by a 0.75 µg/kg/min infusion for 2 hours and 10-hour saline infusion), and 59 argatroban (100 µg/kg bolus followed by a 3 µg/kg/min infusion for 12 hours). The lower number of patients in the argatroban arm was due to the response-adaptive randomization scheme used in the trial, which stopped assigning patients to that treatment when it looked like it wasn’t having a benefit.

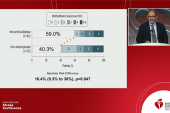

The primary efficacy endpoint was 90-day functional outcome according to the utility-weighted modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, a 10-point scale with higher numbers indicative of better outcomes. The average score was 6.8 with placebo, 5.2 with argatroban, and 6.3 with eptifibatide. The probability of argatroban being better than placebo was 0.2%; for eptifibatide, the figure was 0.9%.

These results were consistent across subgroups defined by age, baseline NIHSS score, type of thrombolytic agent, time to study drug initiation, and use of endovascular therapy.

Looking at 90-day functional outcomes according to rates of mRS scores of 0-1 or 0-2 provided similar results, with worse outcomes among patients treated with argatroban than those given placebo, and similar outcomes in the placebo and eptifibatide arms.

In terms of safety, the rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in the 36 hours after randomization was not significantly higher in patients treated with argatroban (3.7%) or eptifibatide (3.3%) than in those who received placebo (1.8%; P = NS for both comparisons). All-cause mortality, however, was more frequent in the argatroban arm than in the placebo arm (24.1% vs 7.8%; P < 0.001); the rate was 11.8% with eptifibatide, which was not significantly different compared with placebo.

Why the Lack of Benefit?

Addressing the poorer outcomes observed in the patients treated with argatroban, Barreto noted that none of the deaths were deemed to be related to the drug by a safety monitor and also that the low number of patients in this group complicates interpretation of its effects. In addition, argatroban-treated patients tended to have more large-vessel occlusions and more atrial fibrillation compared with those in the other two arms.

It’s unclear why, in contrast to what was suggested in the phase II trials, neither drug added benefit to IV thrombolysis alone. Barreto pointed out, however, that the earlier studies were conducted at a time when thrombectomy was still emerging as a treatment option and was prohibited in most studies. In MOST, 44% of patients underwent thrombectomy.

MOST also differs from the phase II research in that tenecteplase was introduced as an alternative to alteplase and was used in about one-third of participants, Barreto said.

Though this trial establishes that argatroban and eptifibatide don’t provide a clinical benefit on top of IV thrombolysis, this isn’t necessarily the end of adding antithrombotic therapy in this setting, Adeoye said.

“It’s not to say there are not novel drugs, it’s not to say that there are not other drugs, that may be beneficial in that realm,” he said. “I would translate our findings to: definitely not these drugs and back to the drawing board of sorts for us to try and figure out what it is that we missed and what alternatives there may be for this concept going forward.”

Commenting on why MOST failed to show a benefit with these two drugs, Larry Goldstein, MD (University of Kentucky, Lexington), said, “It could be that the underlying hypothesis is wrong or that [the drugs] were just ineffective, at least in secondary thromboses, if that’s what’s underlying some of these problems. But we don’t know that.”

Goldstein told TCTMD it is possible that other types of antithrombotics—factor XI inhibitors, for instance—may be worth exploring as adjuncts to IV thrombolysis. “But when you have two drugs like this, different classes, neither of which showed any hint of benefit and one potential harm, that gives you a lot of pause to continuing down that pathway,” he added.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Adeoye O. Multi-Arm Optimization of Stroke Thrombolysis (MOST) trial. Presented at: ISC 2024. February 7, 2023. Phoenix, AZ.

Disclosures

- Adeoye reports having an executive role with, holding individual stocks/stock options in, and receiving royalties from or holding patents with Sense Diagnostics. He also reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS).

- Barreto reports research funding from the NIH/NINDS.

Comments