‘Mother Ships’ and Helicopters: Speed Is Key for Rural Stroke Thrombectomy

“There’s no one answer for any network,” Marc Ribo says, advising a more-tailored approach based on local circumstances.

How best to deliver endovascular therapy—a proven treatment for acute ischemic strokes caused by large-vessel occlusions (LVOs)—to populations outside of urban areas remains a tricky question, and results from two studies published recently in JAMA provide clues about what works and what doesn’t.

The RACECAT trial, conducted in the Catalonia region of Spain, showed that compared with a “drip-and-ship” approach—in which patients are taken to a local hospital where IV thrombolytic therapy can be administered before patients are transferred to a thrombectomy-capable center—having emergency medical services (EMS) personnel take patients directly to a comprehensive stroke center where the procedure is offered, bypassing the local hospitals (the “mother-ship” approach), did not significantly improve functional outcomes.

And in Germany, a telestroke network in southeast Bavaria, called TEMPiS, decided to test out a third option—flying the interventional team via helicopter from the comprehensive center out to the rural hospitals so the patients didn’t have to be moved. This dramatically reduced the time to delivery of thrombectomy, with hints of improved patient outcomes.

Marc Ribo, PhD (Hospital Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona, Spain), senior author of RACECAT, told TCTMD that for patients who live in an urban area close to a thrombectomy-capable stroke center, “there’s no dilemma or debate—you just need to go to the comprehensive stroke center and don’t stop at the center that cannot offer all the treatment possibilities.”

But the results of these studies, which have been reported at meetings previously and were discussed last week at the European Stroke Organisation Conference in Lyon, France, apply only to nonurban populations and indicate that “there’s no one answer for any network,” he said. Nonetheless, he added, the findings “should help directors of other networks to design according to their needs, to the geographical spread of their centers, to the size of their centers, to the distribution of their population. So they should use our studies . . . to guide their decisions according to the characteristics of their networks.”

Drip-and-Ship Versus Mothership

The safety and efficacy of stroke thrombectomy for patients with LVOs has been established in numerous trials, and the treatment is now strongly supported in practice guidelines. Although there is some evidence supporting the benefits of thrombectomy in later time windows, the results are better when it can be administered closer to stroke onset.

That gave rise to the idea that taking patients with suspected LVOs directly to a thrombectomy-capable center, even if it took a little bit longer initially, would shorten treatment times by eliminating the need for a transfer between centers and ultimately improve patient outcomes. Professional societies have provided some support for that strategy.

The cluster-randomized RACECAT trial, conducted in a network consisting of six thrombectomy-capable centers and 22 local stroke centers, put the concept to the test among 1,401 patients (median age 75 years; 56% men) who were picked up by EMS in areas where the closest hospital was not able to perform thrombectomy. Paramedics administered the RACE scale to determine which patients were likely to have an LVO (score 5 to 9), who were then entered into the trial and randomized to the drip-and ship approach or the mother-ship approach.

The primary outcome was the level of disability at 90 days based on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score among patients eventually diagnosed with ischemic stroke (69% of those enrolled). There was no difference in the median score (3 in both arms) or in the distribution of the scores (adjusted common OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.82-1.29).

Most of the secondary outcomes did not differ between groups either. Those taken directly to thrombectomy centers, however, were less likely to receive IV thrombolytics (47.5% vs 60.4%; OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.45-0.76) and more likely to undergo thrombectomy (48.8% vs 39.4%; OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.13-1.89). Mortality at 90 days was about 27% in each arm.

As to the lack of a difference in outcomes, Ribo had a few potential explanations. First, despite the use of the prehospital RACE scale, there’s no guarantee that patients taken directly to a thrombectomy center will have an LVO, or even an ischemic stroke at all. Second, IV thrombolysis—which may be enough to break up the clot—will be delivered faster if patients are first taken to a local primary stroke center. Third, within this particular stroke network, workflows are very efficient even in the primary stroke centers, reducing the potential difference in treatment times that might be seen in less-streamlined setups, Ribo said. And finally, if a patient has a hemorrhagic stroke instead of an LVO, taking the longer trip to the comprehensive stroke center will delay necessary care and worsen outcomes, which was borne out in RACECAT.

Overall, the trial indicates that either approach can be chosen, Ribo said, noting that within this network, organizers have decided to focus on improving care and reducing workflow times across hospitals, with the drip-and-ship approach used as a general rule. That will allow the local hospitals to maintain their expertise in treating stroke while making efforts to lessen the time it takes to transfer patients who require thrombectomy.

Taking the Operator to the Patient

Looking to overcome the limitations of both the drip-and-ship and mother-ship strategies, investigators within the TEMPiS telestroke network in southeast Bavaria, consisting of five comprehensive stroke centers and 13 primary stroke centers, obtained funding to try an approach of flying an interventional team out to the local sites to perform thrombectomy once it’s determined a patient has an LVO stroke. The first helicopter flight took place in February 2018.

Led by Gordian Hubert, MD (München Klinik gGmbH, Munich, Germany), the researchers reported the results of the first 19 months of the project, during which the flying team was available half of the time. For the other half of the time, patients were transferred between centers as usual.

The nonrandomized analysis included 157 patients (median age 75 years; 51% women) in whom the decision to perform thrombectomy had been made, including 72 treated by the flying intervention team and 85 transferred from a local hospital to a thrombectomy center. Endovascular therapy was more likely to be performed in the former group (83% vs 67%).

The primary outcome was the interval between the decision to perform thrombectomy and the groin puncture at the start of the procedure. The median time was substantially lower for patients treated by the flying team (58 vs 148 minutes; P < 0.001).

The time savings came from parallelization of processes, Hubert told TCTMD. Personnel at the local hospital can make all the preparations for thrombectomy while the intervention team is in the air, allowing groin puncture within minutes of the helicopter touching down. In contrast, when a patient requires transfer, many of the steps need to be performed consecutively.

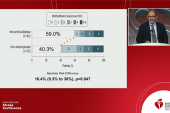

Periprocedural complications, as well as the likelihood of reperfusion, were similar in the two groups, which Hubert said was reassuring. Neurological outcome at 3 months among patients who underwent thrombectomy was a secondary outcome, and although there was a trend toward better functioning according to the distribution of mRS scores in the patients treated by the flown-in team, the difference did not reach statistical significance (adjusted common OR 1.91; 95% CI 0.96-3.88). An post hoc intention-to-treat analysis that included all patients, even those who didn’t undergo thrombectomy, suggested a significant benefit of using the new approach (adjusted common OR 1.91; 95% CI 1.05-3.50).

Hubert noted that the study was not powered to detect a difference in neurological outcomes. Nevertheless, the numerical difference between the two groups is consistent with data from the HERMES collaboration—which pooled information from several randomized thrombectomy trials—regarding the impact of a difference in treatment time of the magnitude observed in this study.

A cost-effectiveness analysis is underway, Hubert said, acknowledging that the cost of the helicopter and pilots is high. Such an effort would be much cheaper, however, in stroke networks that can make use of existing EMS helicopters, he added.

Whether this type of program—which is ongoing and now operating 365 days a year—can be replicated in other parts of the world is uncertain, he said. “For the moment, we only have proof that if there is a quality-ensuring network behind it with telemedicine, then it’s likely to be as good as what we do.”

Improving Stroke Systems of Care

When it comes to the best ways to deliver stroke thrombectomy, both of these studies add to mounting evidence in the area, Hubert said. “I really think we’re sort of closing in on the problem.”

Mobile stroke units—ambulances fitted with CT scanners to diagnose LVO in the field—are primarily good for use in cities, he said. RACECAT shows that it doesn’t help to take patients directly to a thrombectomy center if it adds a lot of time, and the German study demonstrates the impact on treatment times of taking interventionalists to the patients in local centers. “We’re getting closer to realizing which model of care would be good for which geography or which situation and in which population,” he said. “I’m very glad this is going on and there are further study details coming out now so that we finally know how to treat our rural populations well.”

In an editorial accompanying the JAMA papers, Kori Zachrison, MD, and Lee Schwamm, MD (both Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), discuss other opportunities to improve stroke systems of care, pointing to better recognition of stroke symptoms and EMS activation among the public; streamlining of processes after that point, including better prehospital tools to predict the presence of an LVO amenable to thrombectomy; and continued work toward providing equitable access to endovascular therapy.

“When it comes to stroke, time is brain,” they write. “A robust, standardized, protocol-driven system response will be important to ensure consistent, high-quality, and equitable care.”

What that looks like may look different depending on geography, Zachrison and Schwamm suggest.

“Achieving this may require different approaches in countries with coordinated, centralized healthcare planning (such as the countries in which these two studies were conducted) versus countries with more decentralized health care delivery,” they write. “However, the imperative to continually strengthen the stroke system of care and increase the value in the delivery of stroke care remains relevant for all, regardless of location.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Hubert GJ, Hubert ND, Maegerlein C, et al. Association between use of a flying intervention team vs patient interhospital transfer and time to endovascular thrombectomy among patients with acute ischemic stroke in nonurban Germany. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Pérez de la Ossa N, Abilleira S, Jovin TG, et al. Effect of direct transportation to thrombectomy-capable center vs local stroke center on neurological outcomes in patients with suspected large-vessel occlusion stroke in nonurban areas: the RACECAT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Zachrison KS, Schwamm LH. Strategic opportunities to improve stroke systems of care. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The healthcare setup in the study by Hubert et al was funded by Bavarian Public Health Insurances. The study was funded by the Bavarian Ministry of Health and Nursing and the Björn Steiger Foundation.

- Hubert reports receiving institutional funding from the Bavarian Ministry of Health and Nursing, Bavarian Public Health Insurances, and Björn Steiger Foundation during the conduct of the study.

- RACECAT was supported by Fundació Ictus Malaltia Vascular through an unrestricted grant from Medtronic.

- Ribo reports being an advisor and shareholder in Anaconda Biomed and Methinks and receiving grants and personal fees from Medtronic and personal fees from Stryker, Cerenovus, Philips, iSchemaView, and Apta Targets.

Comments