No Increased Bleeding With Alteplase in Stroke Patients on DOACs: Registry Data

The data give no definitive safety answer, but the study authors would like to see practitioners think twice before denying tPA.

Recent use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) does not seem to be associated with increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous alteplase, according to a new study.

The tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) alteplase is standard of care for acute ischemic stroke reperfusion therapy, but current guidelines recommend against its use when a patient has taken their last DOAC dose within 48 hours. While these new data do not provide a definitive answer regarding the safety of administering alteplase in this population, the researchers suggest thinking twice before withholding the quality-of-life-sparing treatment based on fear of bleeding.

“Whenever we see a patient having ischemic stroke while taking one of those new oral anticoagulants, we cannot just simply say that we cannot treat these patients,” senior author Ying Xian, MD, PhD (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas), told TCTMD. “There might be an opportunity to treat, but of course we really need to value the potential benefit and harm of this treatment and make the best decision for these patients.”

But based on this data, Xian said he is convinced that taking DOACs alone should not be an “absolute contraindication.”

Alteplase Following DOACs

For the study, published online ahead of print in JAMA last week, Xian, lead author Wayneho Kam, MD (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC), and colleagues retrospectively looked at 163,038 patients (median age 70; 49.1% women) with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous alteplase within 4.5 hours of symptom onset at 1,752 US hospitals between April 2015 and March 2020; data came from the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke program. The 2,207 (1.4%) patients taking DOACs in the 7 days prior to their stroke were older and had a higher burden of comorbidities and more-severe strokes compared with those not on these medications.

Rates of the primary outcome of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage occurring within 36 hours after intravenous alteplase administration were similar for patients who were taking DOACs (3.7%) and those who were not (3.2%). There remained no difference after adjustment for baseline clinical factors (adjusted OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.70-1.10), and there were no significant differences seen for any secondary safety outcomes, including in-hospital mortality.

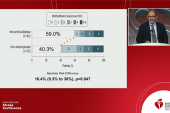

Also, compared with patients not taking anticoagulants, those in the DOAC group were significantly more likely to ambulate independently at hospital discharge (adjusted OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.40), be discharged home (adjusted OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.06-1.29), be free of disabilities (adjusted OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.06-1.42), and be functionally independent (adjusted OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.11-1.45).

In an exploratory analysis of 47 patients from the Addressing Real-world Anticoagulant Management Issues in Stroke (ARAMIS) registry who received alteplase and knew when they took their last DOAC dose, 53.2% said they took their last dose in the 48 hours prior to stroke onset. Of these, only two (8.0%) developed symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, but there were no reported alteplase-related complications in patients who had their last DOAC dose up to 24 hours or longer than 48 hours before the stroke.

‘The Real Risk’

Xian said he was somewhat surprised to see that the risk of bleeding was not higher in DOAC-treated patients receiving alteplase, but the reasons for this are likely varied. Notably, he explained, the patients may not be “fully anticoagulated in the first place, [and] that could explain why their platelet risk is not higher. But since they still have some level of anticoagulation when they have a stroke, that makes for the better functional outcomes after the treatment.”

Strokes in this registry may be due to “nonadherence or interruption of their NOAC [non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant] intake, whereas the ischemic stroke for others may have been a breakthrough event that occurred despite not missing an anticoagulant dose,” the authors write. “By including data from the more-detailed, affiliated ARAMIS cohort, the current investigation provided additional insight into the timing of most-recent NOAC use that was unavailable in earlier studies.”

Xian said it remains unclear whether the specific DOAC a patient is taking matters in terms of outcomes, given that all agents were lumped together in the study. Reversal agents might also be able to reduce the risk of bleeding, he added, but that should be studied further.

In an accompanying editorial, David J. Seiffge, MD (Inselspital University Hospital and University of Bern, Switzerland), said the study “provides important evidence regarding the use of alteplase among patients with ischemic stroke taking prior NOAC therapy, although the findings do not provide a definitive answer to the question of safety.”

Even with the exploratory ARAMIS analysis, he writes, “substantial uncertainty remains about the exact timing of the last NOAC dose among patients in the study.” Also, the potential for selection bias is present given that less than 9% of otherwise eligible patients taking NOACs received alteplase.

“Future studies are needed to provide more-detailed data on patients with recent, verified NOAC intake within 48 hours of alteplase use and to assess the safety profile associated with different patient selection criteria,” he concludes.

Xian also said he is looking forward to data from an ongoing international collaboration trying to identify patients who are taking DOACs within 48 hours. “Now, we cannot treat these patients, but we really want to see what the safety profile is of giving alteplase to these patients,” he said.

His main takeaway for now is that “the real risk is not giving alteplase, but [it is] not giving them the opportunity to treat stroke. Otherwise patients may be left with lifelong disability.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Kam W, Holmes DN, Hernandez AF, et al. Association of recent use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants with intracranial hemorrhage among patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with alteplase. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Seiffge DJ. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy for treatment of acute ischemic stroke in patients taking non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Kam reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Xian reports receiving grants from Genentech, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, the American Heart Association, and the National Institute on Aging, and receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim.

- Seiffge reports serving on advisory boards for Bayer AG and Portola/Alexion and receiving grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, the Bayer Foundation, and Portola/Alexion.

Comments