Novel VECTOR Procedure Creates Percutaneous Aorto-Coronary Bypass

Operators performed closed-chest bypass before TAVI in a high-risk patient with decompensated HF due to a failing aortic bioprosthesis.

A team of investigators have performed the first closed-chest percutaneous bypass procedure in a 67-year-old man who required a new transcatheter valve due to severe degeneration of an existing aortic bioprosthesis but was at high risk of coronary obstruction.

The novel percutaneous procedure, known as ventriculo-coronary transcatheter outward navigation and reentry (VECTOR), involves the use of a covered stent to relocate the coronary artery ostium. Investigators say this approach might be the clinical answer for patients who have no other procedural options.

In a case report published online last week in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, Christopher G. Bruce, MBChB (Emory University, Atlanta, GA), and colleagues report that the intervention was safely performed in the patient and there was no evidence of coronary obstruction following TAVI.

Several leaflet modification options to prevent coronary obstruction are now available for many TAVI patients with extensive calcification, including BASILICA, UNICORN, CATHEDRAL, or snorkel stenting, but there are rare patients with severe aortic stenosis who aren’t candidates for any of those percutaneous techniques. VECTOR represents an “out-of-the-box” attempt to offer a solution, according to senior author Adam B. Greenbaum, MD (Emory University).

Hemostatic covered stents are traditionally used for perforations, but with VECTOR, they were used to connect the left main artery and aorta via holes punched in each, much like is done in bypass surgery. None of the materials used are novel, but the way they were used here is completely new.

“There is a need for these procedures,” Greenbaum told TCTMD. “We can’t let industry drive all the innovation because it takes too long to get through the regulatory process, and patients can’t wait that long.”

Calling VECTOR “an ingenious marriage of structural heart concepts and concepts from the chronic total occlusion [CTO] and PCI world,” Brett Wanamaker, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), told TCTMD he could potentially see this technique used in other cases as well.

“There are a lot of situations in which we have a really hostile coronary vessel that’s very calcified, or maybe there’s a bunch of mangled stent there,” he said. “In the chronic total occlusion world, we’re trying to create a neo-ostium essentially. A lot of times what we’ll do is we’ll go around the occlusion and we will then create a neo-ostium using the subintimal portion of the vessel. But the idea that you could actually just create an entirely new ostium outside of the existing vessel structure proximally is really amazing.”

Similarly, Mathew Williams, MD (NYU Langone Health, New York, NY), lauded the team at Emory for creating and executing this “remarkable” and “boundary-pushing” procedure.

Case Details

Bruce and colleagues developed the VECTOR procedure over 2 years then began looking for patient candidates. They identified a 67-year-old man who had previously received aortic (25 mm Magna Ease; Edwards Lifesciences) and mitral valves (29 mm Epic; Abbott), the latter of which developed degeneration that was then treated with valve-in-valve Sapien3 Ultra Resilia (Edwards Lifesciences). His aortic bioprosthesis also had subsequently degenerated, resulting in decompensated heart failure. Other comorbidities included end-stage renal failure requiring hemodialysis, nondisabling stroke, severe peripheral arterial disease with recent right leg amputation, and an ejection fraction of 20%.

The patient was deemed ineligible for BASILICA, UNICORN, or CATHEDRAL due to heavy calcification on the bioprosthetic leaflets, and snorkel stenting was also ruled out due to the likelihood of stent compression.

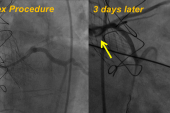

In May 2025, the team performed the VECTOR procedure successfully, anchoring the covered stent to both the LAD and aorta with drug-eluting stents. They then performed balloon-expandable TAVI using Sapien3 Ultra Resilia. Total procedure time was 8 hours and 40 minutes, and total fluoroscopy time was 226 minutes.

The stent graft was patent on CT the day after the procedure, and the patient remains well more than 6 months later. He is currently taking lifelong oral anticoagulation.

We can’t let industry drive all the innovation because it takes too long to get through the regulatory process, and patients can’t wait that long. Adam B. Greenbaum

Greenbaum said his team has subsequently performed VECTOR in a second patient, who received two conduits: one in the left main and one in the right coronary artery. “Both patients are out months now with no signs of any stenosis,” he said.

The complexity and novelty of this procedure mean it’s nowhere close to ready for routine use. “We certainly don’t want the take-home message to be to try this at home; that’s not why we put it out there,” Greenbaum said. “The main reason to put it out there is because maybe there is somebody out there who has a lot to live for and was told there was nothing to be done for them.”

The team plans to offer VECTOR to patients as they see fit going forward, but they aren’t currently planning a study.

A Future CABG Replacement?

The application of VECTOR in patients like the current case represents “compassionate care,” according to Greenbaum. Thinking of the future, he left open the question of whether this technique could one day replace CABG surgery.

“That’s a stretch,” he said. “The LIMA to LAD as a bypass is so magical that [it’s difficult] to think about what it would take to prove to the powers that be that this would be better than that. . . . I’m not saying that that couldn’t be, but I think we’ll all be long gone.”

Wanamaker agreed that it would be hard to prove that VECTOR could best CABG surgery. “One of the advantages of CABG is just the long-term durability and patency of a LIMA, especially in patients who have diabetes and really diffuse disease,” he said. “We’d have to demonstrate that these conduits stay open for years and years, and I think part of the problem is that these patients are so sick. I’m not sure exactly what their lifespan is going to be, but there’s a reason that we’re only entertaining this option.”

Williams said his surgical colleagues are likely “going to be very skeptical” of VECTOR. “A lot of the advantage from surgery really comes from us using a mammary [artery],” he said. “How will the patency of these stents compare to that is a big question. I don’t know the answer to that, but it’s hard to imagine that this would be any inferior to say a vein [graft].”

Regardless, “it’s something that we should pursue,” albeit cautiously, Williams added. “The exciting thing would be is if this was done in some patients with isolated coronary disease, a CTO. I think that’s probably the biggest potential for this.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Bruce CG, Babaliaros VC, Paone G, et al. Percutaneous aorto-coronary bypass graft to prevent coronary obstruction following TAVR: first human VECTOR procedure. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2026;19:e016130.

Disclosures

- Greenbaum reports consulting for Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences, Excision Medical, and Medtronic; holding equity interest in Transmural Systems and Excision Medical; receiving institutional research support from Abbott Vascular, Ancora Heart, Edwards Lifesciences, Gore Medical, JenaValve, Medtronic, Polares Medical, Transmural Systems, and 4C Medical.

- Wanamaker reports serving as a consultant for Boston Scientific.

- Williams reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments