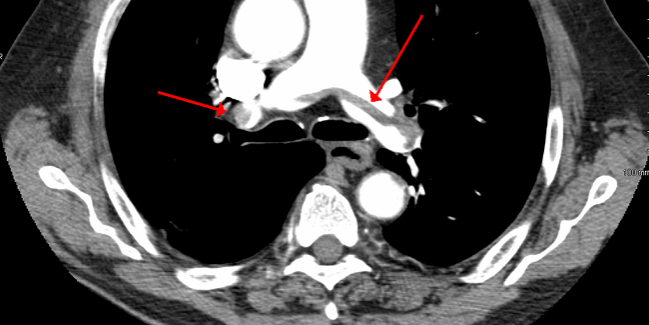

Overuse of CT Scans for Suspected Pulmonary Embolism Persists

Greater use of D-dimer testing may make such evaluations more fruitful, data from 27 US emergency departments suggest.

Emergency physicians are still too often turning to CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) to evaluate suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), recent data from two US metropolitan areas indicate.

Of more than 1.8 million patient encounters across 27 emergency departments in Indiana and the Dallas-Fort Worth area, 5.3% involved some type of diagnostic testing for PE and 2.3% included CTPA. But the yield rate from such testing was low, with only 3.1% of patients who underwent a CTPA scan ultimately receiving a diagnosis of PE.

“Overtesting for pulmonary embolism in American emergency departments remains a major public health problem,” researchers led by Jeffrey Kline, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis), conclude.

Speaking with TCTMD, Kline said a diagnostic yield of about 10% would make the level of testing seen in the study worthwhile. The analysis, published in the January 2020 issue of Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, showed that greater use of D-dimer testing was associated with higher yields, but even adding that blood test would likely not get the yield rate up to 10%, he said.

What’s needed to get there, Kline said, is a combined strategy incorporating evaluation of clinical factors using the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC), D-dimer testing, and then—based on those results—CTPA scans. In order to increase adoption of that approach and reduce overuse of imaging, he added, “it’s going to take groups such as healthcare systems, insurers, and employers of physicians to implement programs that reward and punish doctors. Reward them for doing this and ultimately punish them for not doing it. So, pay for performance.”

A Lingering Problem

This is not the first study to show that emergency physicians are going overboard when it comes to testing for PE. “It’s really fairly well known that we overtest for it,” Kline said. “It’s a potentially lethal disease and there are many, many tales of missed PE leading to death and lawsuits. So it scares emergency physicians and they want to protect their patients. But as a result, they order these CT scans on about 2% to 3% of all patients who come through the emergency department. And that means somewhere around 4 million of these CT scans done per year.” Historic studies show that the yield rate is extremely low, he noted.

More recent data looking into the problem are lacking, however. In this study, Kline et al examined electronic health records and billing data from 16 emergency departments in the Indiana University Health system and 11 in the Baylor Scott & White system in the Dallas-Forth Worth area of Texas. The analysis included more than 1.8 million emergency department visits between January 2016 and February 2019. Of note, emergency care teams in Indiana had not undergone a quality improvement initiative to increase use of D-dimer testing as a screening tool, whereas those in Texas had.

Accordingly, D-dimer testing was more likely to accompany CTPA scans in Texas versus Indiana emergency departments (52% vs 30%). Overall, the rate of PE diagnosis was higher in patients who underwent both CTPA and D-dimer testing rather than CTPA alone (1.8% vs 1.1%).

Is overtesting for PE a major public health problem? I would say missing the diagnosis of PE is more of a major health problem. Victor Tapson

Greater D-dimer use was associated with an increased PE yield rate on CTPA (P < 0.001), the researchers report. “This relationship suggests but does not prove a positive cause-effect relationship between rate of D-dimer ordering and PE yield,” they say. “These data underscore the continued, urgent imperative for increased dissemination and incentivized use of protocol-driven testing for PE. Among other components, these protocols should include the use of exclusionary clinical criteria such as the [PERC rule] and D-dimer before ordering CTPA scans in patients with a nonhigh clinical probability for PE.”

The investigators also looked at vulnerable subgroups and found that the majority of CTPA scans (59%) were done in women, with one-fifth of all scans performed in women younger than 45, “who are probably the subset who are most vulnerable to CT scanning,” Kline said, alluding to the risk of breast cancer from radiation exposure. “So this is, to some extent, a women’s issue,” he added, arguing that the finding “does reflect the need for better communication between patients and doctors.”

Finding the Balance

Commenting for TCTMD, Victor Tapson, MD (Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, CA), said overtesting for PE is a problem, but added that a balance needs to be made between reducing testing and ensuring that PE diagnoses are not missed, something physicians fear.

The approach advocated by Kline—apply the PERC rule, do D-dimer testing, and then proceed to CTPA if the prior tests support it—makes sense, but there are some caveats, Tapson noted. The PERC rule should only be applied when the clinical suspicion for PE is low, and not, for example, on someone who comes in with sudden onset of shortness of breath and hypoxemia, which should indicate a pulmonary embolism, he said. “But when it’s used appropriately, I think it really does help the cause.”

The bottom line is that a physician’s own “clinician gestalt” should come into play when evaluating suspected PE, and in cases of high clinical probability for PE, generally a CT scan is warranted, he said. “I think most people would agree that’s reasonable.”

In the discussion of the best ways to evaluate suspected PE and reduce overtesting, the importance of not missing a PE diagnosis should not be lost, Tapson stressed, pointing out that autopsy studies have shown that most people who die from PE succumb before it’s diagnosed or even suspected.

“Is overtesting for PE a major public health problem? I would say missing the diagnosis of PE is more of a major health problem. But overtesting is a public health problem and we could save a lot of money by reducing the amount of tests,” Tapson said.

Photo Credit: James Heilman, MD [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] via Wikimedia Commons.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Kline JA, Garrett JS, Sarmiento EJ, et al. Over-testing for suspected pulmonary embolism in American emergency departments: the continuing epidemic. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;13:e005753.

Disclosures

- The paper was funded by the Eli Lilly Foundation Physician Scientist Initiative.

- Kline reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments