Real-World Study Raises Concerns About Initiating Carotid Stenting in Acute Phase

Stroke or death risk was increased within the first few days of a neurologic event, but the lack of embolic protection in the study raises some red flags.

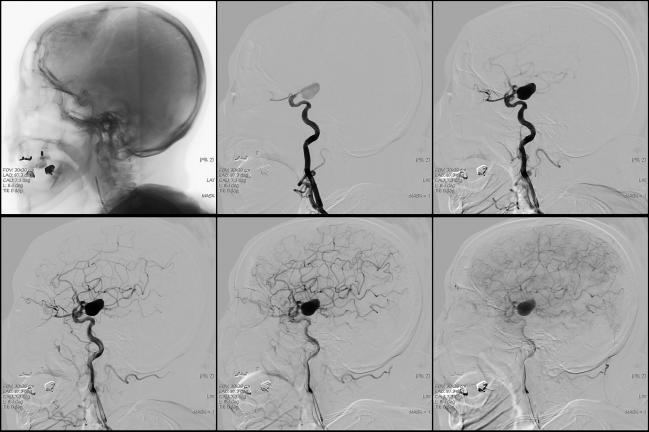

Real-world data confirm an observation previously seen in randomized trials that the risk of stroke and death may be increased when carotid artery stenting (CAS) is performed within days of symptom onset in patients with carotid stenosis.

“Based on the current and other published evidence, carotid endarterectomy is likely more beneficial than carotid artery stenting in the first days after the index neurologic event,” write researchers led by Pavlos Tsantilas, MD (Technical University Munich, Germany).

Their data are based on a review of patients entered into a mandatory national quality assurance database of 4,717 elective CAS procedures performed in symptomatic patients in Germany between 2012 and 2014. The findings are similar to those of a recent analysis of four randomized controlled trials comparing carotid endarterectomy (CEA) with CAS in symptomatic patients, which also found higher risk of stroke or death when CAS was performed within 7 days of symptom onset.

However, in an interview with TCTMD, L. Nelson Hopkins, MD (University at Buffalo, NY), pointed out that the new study shows a worrisome lack of attention to embolic protection in Germany, with it being used in less than 50% of the CAS procedures reported. He added that the paper “does a great disservice to patients and to carotid stenting.”

Hot Plaques and Old Trials

In the study, published online March 27, 2018 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, any in-hospital stroke or death occurred at a rate of 6% in patients treated in the first 2 days after the index neurologic event and 4.4% in those treated in the first 3 to 7 days. In contrast, the rates were 2.4% and 3% for those treated at 8 to 14 days and 15 to 180 days, respectively.

In adjusted analyses, those treated between 8 and 14 days showed a decreased risk for any in-hospital stroke or death compared to the group treated in the 0 to 2 day window (RR 0.47; 95% CI 0.28-0.79). Additionally, those treated between 3 and 14 days had a decreased risk of all-cause death compared with those treated within 2 days. The index event was a TIA or minor stroke (Rankin 0-2) in the majority of patients.

Other research has probed the relationship between treatment timing and adverse events, looking at one or both approaches. In a 2016 study, Tsantilas and colleagues looked at symptomatic patients in the same German database who were treated by CEA, and found no significant associations between time interval from the index neurologic event and the combined risk of stroke and death. That study concluded that in clinically stable patients, CEA could likely be performed safely as soon as possible after the neurological index event to remove unstable or “hot plaques” that could lead to stroke.

Then there is the analysis of the four randomized trials (EVA-3S, SPACE, ICSS, and CREST). That study, from the Carotid Stenosis Trialists’ Collaboration, found the risk of stroke and death to be nearly seven times higher when patients were treated in the first week of symptoms with CAS as opposed to CEA, and concluded that surgery was safer in the acute phase. However, embolic protection was only mandatory in CREST, making it impossible to determine if the poorer results for CAS compared with CEA in the setting of early intervention held true under optimal stenting conditions. Furthermore, the trials were conducted in the early days of the carotid stenting experience.

But Tsantilas and colleagues say that analysis, together with the new data, suggest that “treatment with CAS seems to be more dangerous in the early period after the index event.”

Safer With Time

To TCTMD, Hopkins said he disagreed. “You have to throw out those older trials because as experience has grown the procedure has become much, much safer,” he said. Importantly, Hopkins said discouraging the practice of carotid stenting in the acute phase is unjustified and if anything, is a cautionary tale about what can happen when embolic protection is not used.

“In the acute phase not only is embolic protection mandatory, but we now know that proximal embolic protection is a better choice for these patients with a hot plaque,” Hopkins said. “What may be happening in Germany is that the sicker patients are being referred for carotid stenting and maybe that plus the fact that there’s so little use of embolic protection is slanting the results.”

In their paper, Tsantilas and colleagues suggest that one reason surgery may be safer is because removing an unstable plaque with distal and proximal clamping of the artery provides better protection than pushing the plaque back against the wall with a stent.

But Hopkins said that suggestion does not take into account newer technologies that now include a fine mesh cover over the stent that prevents the plaque from pushing through the struts and embolizing. He suggested that to further investigate this issue in Germany it would make sense to look specifically at cardiologists who are using embolic protection, adding that the study may be providing an unnecessarily skewed view of current practice in that country.

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Tsantilas P, Kuehnl A, Kallmayer M, et al. [Risk of stroke or death is associated with the timing of carotid artery stenting for symptomatic carotid stenosis: a secondary data analysis of the German statutory quality assurance database.] (http://jaha.ahajournals.org/content/7/7/e007983) J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Tsantilas reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Hopkins reports owning stock in Silk Road and Boston Scientific.

Comments