SCOT-HEART: A Win for CT Angiography in Chest Pain Workup Prompts Cacophony of Reactions

In the week since the randomized trial results were aired, experts have reacted with both jubilation and incredulity at the reduction in hard events seen with CTA.

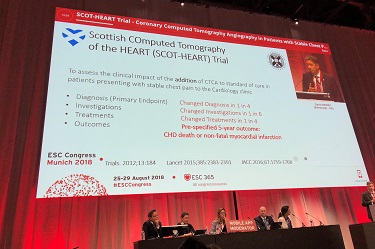

MUNICH, Germany—Some are hailing the 5-year results from SCOT-HEART, showing that a chest-pain workup strategy using coronary CT angiography (CTA) is superior to standard care, as the most powerful, positive data to come out of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2018.

“This now begs the question: should CT angiography be viewed as the test of choice in patients with stable chest pain?” presenter David Newby, MD, PhD (University of Edinburgh, Scotland), asked the audience as he concluded his late-breaking talk on the opening day of the meeting.

“This is one of the most impactful trials, not just in imaging but in cardiovascular medicine,” one of the session discussants, Todd C. Villines, MD (Uniformed Services University School of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland), said following SCOT-HEART’s presentation.

Others, however, have balked at the results, prompting some sparring on Twitter that lasted most of the week.

The SCOT-HEART study reports that doing a CT scan in pts w/ chest pain reduces heart attack by 41%.

— John Mandrola, MD (@drjohnm) August 26, 2018

And NEJM publishes it

This, my friends, deserves serious critical appraisal>> https://t.co/MZf3EoKPns#ESCcongress#CardioTwitter#FOAMed

Thx to @AndrewFoy82 pic.twitter.com/xyZEU8aJ0k

Are u kidding me. Not a serious response to what are important findings. If u know the connection...plaque... med rx.. Reduce ACS, then these findings are so believable. https://t.co/hOxcs0J84w

— Leslee Shaw (@lesleejshaw) August 26, 2018

SCOT-HEART trial is the ORBITA of 2018. Except, everyone’s arguments seem to be pointing in every direction

— Saurabh Jha (@RogueRad) August 28, 2018

SCOT-HEART was published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Key Findings: SCOT-HEART

The randomized controlled SCOT-HEART trial, conducted in 4,080 patients across 12 hospitals in Scotland, had complete data encompassing nearly 20,254 patient-years of follow-up. At a median of 4.8 years, the primary clinical endpoint of coronary heart disease death or nonfatal MI was reduced by a whopping 41% when CTA was used instead of standard care alone to guide patient management. That difference was driven by a lower rate of nonfatal MI, which was reduced by roughly the same degree as the primary endpoint over follow-up.

Importantly, while both invasive angiography and coronary revascularization were more common among patients randomized to the CTA-guided management in the early months of the study, by 5 years there were no differences between groups. Indeed, in a landmark analysis looking at invasive tests and treatments between 1 and 5 years, both angiography and revascularization were more common in the standard care group.

SCOT-HEART Events: Median Follow-up of 4.8 Years

|

|

Standard Care (n = 2,073) |

CTA + Standard Care (n = 2,073) |

HR (95% CI) |

|

Primary Endpoint |

3.9% |

2.3% |

0.59 (0.41-0.84) |

|

Nonfatal MI |

3.5% |

2.1% |

0.60 (0.41-0.87) |

|

Invasive Angiography |

24.2% |

23.7% |

1.00 (0.88-1.13) |

|

Revascularization |

12.9% |

13.5% |

1.07 (0.91-1.27) |

“The benefits appear to be attributable to better targeted preventive therapies and coronary revascularization,” Newby said, noting that statin use was significantly higher among patients randomized to the CTA-based strategy at years 1 through 5 of the trial. Frequency of statin use according to patient 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (using the ASSIGN score) showed a near doubling in the use of statins among patients found to have CAD on cardiac CTA versus patients with no CAD. Use of antianginal medications also was significantly higher among the CTA-managed patients than among those initially worked up using standard care (OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.05-1.54).

Physician reaction to SCOT-HEART’s 5-year outcomes was instant and effusive.

“This was the best study ever done for CCTA findings,” James Min, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY), said after trooping up to the microphone following Newby’s presentation.

The reaction on Twitter, at least initially, was equally impressed.

Game changing RCT demonstrating reduced death from coronary heart disease or non fatal MI at 5 years after #CTCA in patients with suspected angina. Targeted medical therapy improves outcomes. #ESCCongress https://t.co/MiuFN2k6Qb

— Andrew Chapman (@chapdoc1) August 25, 2018

But skeptical counterpoints swept in swiftly thereafter with critical appraisals by @AnilMakam, saying “the trial falls short,” and @DrJohnM with @AndrewFoy82, calling the results “too good to be true.” This in turn prompted further critique-critiques, most notably by @rwyeh: “This isn’t a game changer in my book, but certainly provocative and looks well conducted. I’d love to see replication. But I don’t find any of it implausible.”

Sorting Through SCOT-HEART

Speaking with TCTMD, a range of experts tried to sort through the hubbub to address the concerns raised about the trial, to highlight what the trial adds, and to clarify what it leaves open for further discussion and research.

Several critics pointed to the lack of a plausible mechanism to explain the effect size. The reduction in death and MI, they argued, is out of scale with the increased uptake of primary prevention medications. To this point, several observers countered that the credit doesn’t go solely to better medical adherence.

“I think the preventive therapies probably explain some of it,” Min told TCTMD. “But it’s possible that lifestyle modification also addressed some of that improvement. We know that if patients are aware of their disease, if they can visualize their coronaries—and we know this from calcium scoring studies— that they can change their behavior.”

Min also believes “implementation science” plays a role. “Once you know somebody is sick, you take care of them more intensively and I think that probably makes a big difference,” he said. “We don’t talk about this much, because it’s not some new medicine or some new stent, but the act of delivering more-intensive care has been demonstrated to save lives. So I think the mechanism here is multifactorial. It’s a combination of a lot of things.”

Once you know somebody is sick, you take care of them more intensively and I think that probably makes a big difference. James Min

Manesh Patel, MD (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC), chaired the writing group for the 2017 stable ischemic heart disease appropriate use criteria. He also believes that physicians reacting to CTA results may have played a role, particularly since, given the patterns of care in Scotland, they got test results faster and likely acted on these several weeks sooner than physicians who were sending patients through the standard gamut of tests, ultimately leading to an invasive angiogram that would then prompt revascularization or intensification of medical care.

“A noninvasive test cannot make you live longer,” Patel told TCTMD. “It’s how you act on the information. And SCOT-HEART showed us that when people have chest pain evaluations—if physicians can get to the anatomic or risk information faster—those patients might do better, especially if these patients are high risk over the long haul.”

Jonathon Leipsic, MD (St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver, Canada), took a similar position. “CT shows you the plaque and allows you to say, ‘Hey, this person has extensive coronary atherosclerosis, we should treat this person, or no, this person has no disease, they probably don’t need to be treated.’ It gives you certainty: you send more patients early for invasive testing because you see severe disease,” he explained. “In the stress-testing arm, you don’t really know if they have disease, so you send them home. And they come back and say: ‘Doc, my chest is still hurting.’ And what do you do then is [send them] to the cath lab and 60% of the time you don’t find coronary disease.”

In addition to the acting-earlier hypothesis, Newby gave some of the credit to patients themselves. “What SCOT-HEART data does suggest is that if you know you have coronary disease, you should take your tablets more, you might stop smoking more, you might diet and exercise more,” he said during the Q&A that followed his presentation.“We don’t know that from SCOT-HEART, but all of these things do come together so that if you know you’ve got something, you’re much more likely to adhere to your treatments and to do something about that.”

Both Patel and Newby stressed that such a hypothesis warrants further testing.

“SCOT-HEART 2,” Newby hinted “might be a primary prevention trial comparing a use of risk score versus CT angiography.”

Another criticism of SCOT-HEART was that there was no formal, independent adjudication of myocardial infarction in the trial, with endpoints classified primarily on the basis of diagnostic codes. Numerous commenters, however, pointed out that this was unlikely to have driven the endpoint difference, noting that this probably meant underestimation of MIs, something that would have affected all of the patients in the study, regardless of randomization.

Yousif Ahmad, MD (Imperial College London, England), put it succinctly. “I’m not saying there’s not imperfections in coding,” he told TCTMD. “I’m just saying the imperfections would be present in both arms.”

Breaking From Promise

Baffling to some is the fact that SCOT-HEART did not replicate the findings seen in other large randomized trial of CTA as a decision-making tool: PROMISE.

In an editorial accompanying the publication of SCOT-HEART, Udo Hoffmann, MD (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), and James Udelson, MD (Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA), point out that PROMISE, which also randomized patients to either CTA or functional testing, showed no difference in outcomes over a median follow-up of 2 years.

“Although both trials had one group in which management was informed by CTA, an important difference between the two trials was the comparator group,” they write. “In PROMISE, functional testing was predominantly stress imaging (nuclear or echocardiographic) and only 10% of patients underwent exercise electrocardiographic (ECG) testing. In the SCOT-HEART trial, however, the standard-care strategy was predominantly stress ECG testing, and few patients (approximately 10%) underwent an imaging test. One might conclude, then, that the CTA strategy was associated with fewer myocardial infarctions in the SCOT-HEART trial because of the suboptimal stress ECG comparator and because of the potentially suboptimal management that was based on that strategy.”

“Although both trials had one group in which management was informed by CTA, an important difference between the two trials was the comparator group,” they write. “In PROMISE, functional testing was predominantly stress imaging (nuclear or echocardiographic) and only 10% of patients underwent exercise electrocardiographic (ECG) testing. In the SCOT-HEART trial, however, the standard-care strategy was predominantly stress ECG testing, and few patients (approximately 10%) underwent an imaging test. One might conclude, then, that the CTA strategy was associated with fewer myocardial infarctions in the SCOT-HEART trial because of the suboptimal stress ECG comparator and because of the potentially suboptimal management that was based on that strategy.”

Patel, who was an investigator for PROMISE, observed that patients in SCOT-HEART were “slightly higher risk” since they had already undergone clinic consultation, including an exercise ECG if deemed appropriate, before being randomized head-to-head. This slightly-higher-risk status might have been enough to tip the scales in favor of CTA in SCOT-HEART, Patel hypothesized, noting that in PROMISE, too, “we saw a little bit of signal at 1 year . . . but over the long haul there wasn’t a clinically significant difference.”

Believing the Data

Several experts who spoke with TCTMD pointed out that CT imaging, for years, was dogged by a fly-by-night reputation, with a lot of testing taking place in the private practice setting. Facing a chorus of complaints, CT advocates buckled down and did the large randomized trials that many had been calling for.

“I think this was a really earnest effort at trying to develop evidence to either support or refute the notion that this is a useful technology to employ for patients with suspected coronary disease,” Min told TCTMD. “This was a prespecified endpoint; it wasn’t like they mined the data after the trial was done. They had prespecified the 5-year endpoint at the inception of this trial, and they anticipated that it would take years to really see the true benefit, that visualization of atherosclerosis and the power of that would take time to show.”

In clinical practice, I suspect we are testing a lot of these kinds of patients. Manesh Patel

Min added that he was “a little surprised” by the reaction to the trial, noting that critics have long called for randomized data, then when they got it, seem unwilling to believe it.

“I thought this was a fairly remarkable result, that a diagnostic imaging test could influence care that much to really reduce myocardial infarction and death in a sustained manner, not just for 2 years and then it pops back up again,” he said. “To me, I was impressed, and I’m not involved with this study. I thought this was the best study that CT has ever produced.”

Patel, too, seemed surprised by the reaction. “I saw some of the criticisms of this paper—that these were low-risk people, that the event rates are too low, that these patients may not represent things we see. But in clinical practice, I suspect we are testing a lot of these kinds of patients,” he commented.

The fact that SCOT-HEART randomized patients after an initial evaluation for chest pain was identified as a flaw in the study design, but that doesn’t mean that’s not how CT is used now, Patel pointed out. “It’s maybe not as clean as some people would like, but it represents practice very well,” he said. “I think what happened is that the data are the data. I believe they randomized the patients, and I think those are the event rates they saw.”

People can debate the mechanisms, he continued, but it’s hard to dispute the findings from a randomized trial. The bigger questions, he continued, are: “Can we reproduce it? Can we identify why in that healthcare system this works and will it work in other systems?”

Should Guidelines Change?

The question on everyone’s lips is whether CT angiography will “move up” in US and European guidelines, where it is currently considered a secondary test. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that coronary CTA is an option in patients with contraindications to stress testing or who are unable to exercise, but new stable ischemic heart disease guidelines are due out this fall.

European guidelines, likewise, state that CTA can be used as “an alternative” to stress imaging techniques, with an emphasis in patients at the lower range of risk in whom exercise ECG or stress imaging are inconclusive or contraindicated. Only in the UK have the National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations stated that CT angiography should be the first-line investigation for patients with stable chest pain, as well as for nonanginal chest pain with ECG changes suggestive of coronary artery disease.

“The data are so compelling, but there are reimbursement issues in the US that remain, and there are preauthorization limitations,” Leipsic observed to TCTMD. “But if these data don’t continue to push the guidelines in the US, well . . . . ,” Leipsic’s voice trailed off. “We’ve seen the NICE guidelines say CT should be the first-line strategy, and I think in the US we will at least see a shift towards that direction. You can’t deny the data.”

Pamela Douglas, MD (Duke University, Durham, NC), also predicts a change. “Between PROMISE and SCOT-HEART, CTA is at least equivalent to stress testing, with a level of evidence A: two large randomized trials,” she told TCTMD in an email. “I would propose CTA become a class I for initial testing in stable-symptoms/intermediate-risk patients, even in those who can exercise and have an interpretable ECG. The 5-year SCOT-HEART data is just the icing on the cake.”

She continued: “I don’t know that I would downgrade stress testing to a lesser class recommendation, the way the Brits have done, just move CTA up alongside them.”

“Something new will happen,” Min predicted. “Whether they will consider the SCOT-HEART results or not, I don’t know, but I think. . . it’s at least reasonable to consider CTA as a first-line test as compared to any other diagnostic workup.”

Patel acknowledged some of the protests on Twitter, calling for cheaper tests with no radiation risk to remain a priority in chest-pain assessment. But here, too, he pointed out, data are lacking. By contrast, he said, with SCOT-HEART, “we have head-to-head, randomized trial data of noninvasive testing showing clinical event differences. That should affect guidelines. And for those who speak to other noninvasive modalities, they should point to this study and do more things like this to try got get those other tests forward in the guidelines.”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

The SCOT-HEART investigators. Coronary computed tomography and the future risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Hoffmann U, Udelson JE. Imaging coronary anatomy and reducing myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Newby reports consulting/royalties/owner/stockholder with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, and Toshiba, and holding research contracts with all of the above plus Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman La Roche, Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, GSK,and Siemens.

- Min reports research support from GE Healthcare; serving on the medical advisory board for Arineta and GE Healthcare, and equity interest in Cleerly.

- Patel reports working on ADVANCE, which was funded by HeartFlow, PROMISE, funded by the NHLBI, and DEFINE-FLAIR, funded by Volcano and Philips.

Comments