Self-Expanding TAVI Holds Up to Surgery Out to 3 Years in Low-Risk Patients

The real question, however, is what will happen over longer-term follow-up. Evolut Low Risk will track patients out to 10 years.

NEW ORLEANS, LA—TAVI with a self-expanding, supra-annular valve has durable effects compared with SAVR for up to 3 years in patients with severe aortic stenosis and at low surgical risk, findings from the Evolut Low Risk trial show.

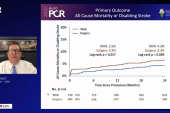

At that time point, the rate of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke—the primary endpoint—was 7.4% in the TAVI arm and 10.4% in the surgery arm (P = 0.051), with no differences across subgroups. The absolute difference between arms is similar to what was seen at 1 year (1.8%) and 2 years (2.0%).

Also consistent with earlier time points, TAVI maintained an advantage over surgery in terms of hemodynamics and the rate of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), but came with higher rates of mild paravalvular regurgitation and pacemaker implantation, John Forrest, MD (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), reported here at the American College of Cardiology/World Congress of Cardiology (ACC/WCC) 2023 meeting.

The results, published simultaneously online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, “provide physicians, patients, and heart teams with important data while making that shared decision-making process,” Forrest said. “The excellent valve performance and durable outcomes out to 3 years in low-risk patients affirm the role of TAVR with the Evolut valve in this patient population.”

He acknowledged, however, that the length of follow-up remains a limitation.

“These are 3-year results, and longer-term data are needed to evaluate the impact that valve design, hemodynamics, new pacemakers, and other differences in secondary endpoints may have on the longer-term outcomes in these low-risk patients we expect to live a long time,” he said.

Indeed, commented cardiac surgeon Gorav Ailawadi, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), who was not involved in the trial, 3 years is too short to make any firm conclusions about the long-term durability of heart valves. But, he told TCTMD, “having said that, there doesn’t seem to be any big difference between 2 and 3 years in terms of the durability, which is really encouraging.”

Evolut Low Risk Trial

The main 2-year results of the Evolut Low Risk trial showed that TAVI with a self-expanding valve—including CoreValve, Evolut R, or Evolut PRO (Medtronic)—was noninferior to SAVR in terms of the rate of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke. At the same time, the PARTNER 3 trial demonstrated that TAVI with the balloon-expandable Sapien 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences) topped surgery when it came to the rate of death, stroke, or rehospitalization at 1 year, also in a low-risk patient population. Both trials supported the US Food and Drug Administration’s expansion of TAVI indications to include patients irrespective of surgical risk.

What’s lacking in the low-risk population, however, is information on what happens beyond 2 years. Longer-term data are particularly important in this group with many potential years of life left to guide shared decision-making discussions about TAVI versus surgery.

The 3-year results from Evolut Low Risk begin to push beyond that time point. The trial, conducted at 86 sites in Australia, Canada, France, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the US, enrolled patients with severe aortic stenosis and a low risk of death from surgery (< 3%) based on a heart team evaluation. Ultimately, the trial included 1,414 patients (mean age 74 years; 35% women) with an attempted transcatheter or surgical implant. The mean STS score was 2.0% in the TAVI arm and 1.9% in the surgery arm.

As seen at 2 years, the rate of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke was numerically but not significantly lower in the TAVI arm (7.4% vs 10.4%; P = 0.051). What differs from earlier time points, which showed a maintenance of the separation of curves at 1 and 2 years, however, is that between 2 and 3 years the curves “didn’t start to come together but actually if anything separated a little bit,” Forrest noted.

TAVI yielded nonsignificantly lower rates of each of the components of that endpoint—all-cause mortality (6.3% vs 8.3%; P = 0.16) and disabling stroke (2.3% vs 3.4%; P = 0.19).

At 3 years, TAVI remained associated with a higher rate of permanent pacemaker implantation (23.2% vs 9.1%) and a lower rate of new-onset AF (13.1% vs 40.0%; P < 0.001 for both). There were low overall rates of total valve thrombosis and reintervention (1% or less) that did not differ between trial arms.

The greater improvement in hemodynamics—mean gradient and effective orifice area—with TAVI versus surgery at earlier time points remained at 3 years, and transcatheter treatment carried a lower risk of moderate or worse patient-prosthesis mismatch (10.6% vs 25.1%).

Mild paravalvular regurgitation was still more frequent after TAVI at 3 years (20.3% vs 2.5%), although most patients were treated with the Evolut R device, which doesn’t have an external pericardial wrap. The newer Evolut PRO and PRO+ valves, the investigators note in their paper, “have an external pericardial wrap on the lower valve frame that has been shown to further reduce paravalvular regurgitation.”

They performed a landmark analysis showing that the amount of paravalvular regurgitation seen on a 30-day echocardiogram was not significantly related the rate of the primary endpoint at 3 years.

Gains in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score were similar in both groups, with about a 20-point increase from baseline to 3 years. The proportion of patients who improved by at least one NYHA functional class by 3 years was 72.7% in the TAVI arm and 68.1% in the SAVR arm.

Pacemaker Concerns

Ailawadi said the study “adds to increasing evidence about the overall safety of TAVR” in these types of patients, but he had some caveats.

First, although the patients were defined as low risk, they were higher risk than what some physicians would consider low risk in current practice, he said.

In addition, 3 years is not enough time to provide an assessment of long-term durability, he said, noting that, historically, some surgical valves that looked good at 3 years started failing at 5 to 6 years. For high-risk patients, data out to 3-5 years provide a useful look at durability, but in low-risk patients, a longer look is necessary.

Extending the follow-up will provide information on the significance of the difference observed in mild paravalvular regurgitation, and whether it progresses. But a bigger concern, Ailawadi said, is the impact of the higher rate of pacemaker implantation after TAVI.

“In a young, low-risk population, that has important implications. We see a lot of late impacts of pacing, both on ventricular function and, importantly, on tricuspid valve function,” he explained.

He said he was hopeful that pacemaker rates are not that high for TAVI procedures being performed today, but regardless of the actual rates, it’s important to be honest with patients about the risk of pacemaker implantation when discussing options for aortic valve replacement. “Patients are pretty enthusiastic about TAVR, and I think as long as they’re well-informed about the pacemaker risk and what the implications are with that and understand that, I think, then, it’s fine to proceed,” Ailawadi said, adding that “I think there’s a small percentage of patients that feel like a pacemaker is something they don’t want to have to deal with.”

Addressing the pacemaker issue in a panel discussion following his presentation, Forrest said, “I think it’s fair to say that putting in a pacemaker is not a benign thing, and we should aim to decrease it as much as we can.” A subanalysis confirmed that patients who received pacemakers fared slightly worse than those who didn’t, he said, but added that there are data from the TVT Registry indicating that changes in implantation techniques for self-expanding valves have brought pacemaker rates down into the high single digits. Advancements in valve design will help as well.

Forrest was also asked about coronary access after TAVI and whether there were any issues through 3 years. In the TAVI arm, 24 patients required PCI during that span, and all of the procedures were successful. But when asked to rate the difficulty of the coronary procedures, operators deemed them easy or moderately easy in roughly 80%, and difficult in about 20%. “It is slightly more challenging to engage the coronaries, [as] you have to go through the frame,” he said. “But it’s very feasible and was done successfully in all the patients.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Three-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The trial was funded by Medtronic.

- Forrest reports having received grant support/research contracts and consultant fees/honoraria/speakers bureau fees from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic.

- Ailawadi reports consulting for several companies that make TAVI and SAVR valves, including Abbott, Anteris, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

Comments