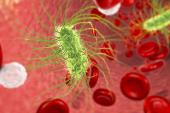

Sepsis Emerges as Powerful CVD Risk Factor in Large US Analysis

Heightened awareness about risk after a sepsis hospitalization may change treatment and follow-up plans, the authors say.

Sepsis diagnosed during a hospital stay may pose an increased risk for CV events, rehospitalization, and reinfection over the long term, according to a study of more than 2.2 million Americans. The risk was particularly increased for heart failure hospitalization.

According to the study, published Wednesday in the Journal of the American Heart Association, the excess risk associated with sepsis was seen within the first 6 to 12 months after hospital discharge and accumulated over the 12-year follow-up period. Patients with sepsis classified as implicit (presence of infection and organ failure) or explicit (documented diagnosis of sepsis or septic shock) had higher rates of all adverse events than those without sepsis.

The authors say the findings highlight the role that sepsis during hospitalization can play as a continuous and powerful risk factor for atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic CV events.

“We specifically looked at high-risk patients, so even the patients in our population who didn't have sepsis had a very high cardiovascular risk to start. It’s an important point that even among high-risk patients, the risk of sepsis was additive,” lead author Jacob C. Jentzer, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), told TCTMD. “Our analysis showed particularly high risk for heart failure, but also coronary events, arrhythmias, and venous thromboembolism, in patients who survived sepsis.”

One of the most important takeaways is the need for increased awareness that the hospital stay isn’t where the sepsis-related problems end, Jentzer added. “Along with that is the question of when you have a patient who has some cardiovascular risk factors and they survive sepsis, do you need to focus on intensifying the risk factor management, and if so, how?”

Prior research has indicated that sepsis and pneumonia, as well as influenza and shingles, may be potential triggers in some individuals for MI, stroke, and other CV events either during the active infection phase or later. Although a clear biological mechanism to connect sepsis with subsequent CV events is elusive, there is evidence to suggest that a sepsis infection puts some patients into a prolonged state of persistent immune dysfunction and systemic inflammation, say Gabriel Wardi, MD, MPH (UC San Diego Health, CA), and colleagues in an accompanying editorial.

The presence of inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and neurohormonal activation in some patients with sepsis may therefore accelerate thrombotic conditions, they explain. “Identifying those patients at high risk of endothelial dysfunction and persistent inflammation while in the hospital or shortly after could allow for more-personalized care and improved risk stratification.”

Early and Late Events Seen

Jentzer and colleagues examined data on more than 2.2 million patients in the United States (mean age 64 years; 54% women) who were hospitalized for medical/nonsurgical reasons for at least 2 nights. All had preexisting CVD, a CVD diagnosis during the index hospitalization, or one or more CVD risk factors. More than one-third had a diagnosis of sepsis during at least one hospitalization over the study period, which encompassed 2009-2019. Over half of all sepsis cases were classified as implicit.

Compared with patients who did not develop sepsis, those who did were older, more likely to have Medicare Advantage, and had a greater number of infections, comorbidities, CVD risk factors, and preexisting and/or new CVD diagnoses while hospitalized.

Compared with non-sepsis patients, the sepsis group was at increased risk over the follow-up for all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.25-1.28), all-cause rehospitalization (adjusted HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.37-1.39), CV-related hospitalization (adjusted HR 1.43; 95% CI 1.41-1.44), the composite of all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization (adjusted HR 1.35; 95% CI 1.34-1.36), and the composite of all-cause mortality and CV hospitalization (adjusted HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.35-1.38). These rates were higher in the sepsis group at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year after discharge.

Posthospitalization adverse events were highest overall in patients with implicit sepsis and lowest overall in patients with no sepsis.

Future Considerations

The most common adverse CV event in patients who developed sepsis was heart failure hospitalization (adjusted HR 1.51; 95% CI 1.49-1.53), which Jentzer said points to underlying mechanisms that allow sepsis-induced inflammation and neurohormonal activation to kick-start myocardial dysfunction, or could simply indicate that events in some patients reflect a decrease, interruption, or failure to restart HF medications during or after the sepsis hospitalization.

More research is needed to understand whether standard secondary prevention therapies such as aspirin, statins, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists, or beta-blockers can prevent CVD events in sepsis survivors, he added.

Also on the horizon, Wardi and colleagues say, ongoing research is looking at the development and understanding of sepsis phenotypes, which could allow for rapid detection and treatment of those at highest risk for poor outcomes.

The editorialists note, however, that while the new data “provide evidence that sepsis may be an important risk factor for cardiovascular complications across a broad group of patients,” the study population was not stratified by 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk, which might have helped clarify the true contribution of sepsis to subsequent risk of CV events.

To TCTMD, Jentzer said the criticism is valid but added that he doesn’t feel it invalidates the paper, noting that the information was not available within the confines of the database that was used and that even established ASCVD calculators are subject to change over time.

“What would be ideal as a next step is if you had a group of patients who had well-defined ASCVD risk and followed those who developed sepsis and those who did not. . . . You could then determine if sepsis really was likely to be a dominant cause versus perhaps a disease process that affects people who are already high risk,” he concluded.

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Jentzer JC, Lawler PR, Van Houten HK, et al. Cardiovascular events among survivors of sepsis hospitalization: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e027813.

Wardi G, Pearce A, DeMaria A, Malhotra A. Describing sepsis as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e028882.

Disclosures

- Jentzer and Wardi report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments