To Stent or Not to Stent? iFR vs FFR Late Breakers at ACC 2017 Seek to Shake Up Treatment Decisions

DEFINE-FLAIR and iFR-SWEDEHEART, with a combined total of 4,500 patients, may pave the way toward wider use of physiologic assessment.

How to know exactly which lesions merit treatment and which can safely be left alone for the time being stands out as one of the most compelling questions in interventional cardiology. This Saturday at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Sessions, two trials—DEFINE-FLAIR and iFR-SWEDEHEART—could, depending on how their results pan out, translate into greater expansion of physiologic assessment into cath labs across the world, experts say.

Both studies pit instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR; Volcano Corporation), a relative newcomer, against fractional flow reserve (FFR), whose value was demonstrated over the years in DEFER, FAME, and FAME 2. FFR involves using adenosine and measuring the pressure gradient across a lesion during hyperemia, whereas iFR is calculated during the resting period and does not require use of hyperemic agents. DEFINE-FLAIR and iFR-SWEDEHEART offer a combined total of 4,500 patients and will go a long way toward settling whether iFR can match FFR in terms of clinical outcomes, in this case all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and unplanned revascularization at 1 year.

In the words of DEFINE-FLAIR principal investigator Justin Davies, MBBS, PhD (Imperial College, London, England), who spoke with TCTMD this week ahead of ACC 2017, “there’s a mass of data here which we hope will be beneficial to physicians.”

Both studies are unique in that they involve patients with “intermediate lesions” in which the physiological severity of the lesion is uncertain and include a “very real-world population,” Davies said. Rather than looking at patients with known disease, investigators are studying patients with stable angina or NSTE ACS who underwent coronary angiography and had an indication for physiologic assessment—namely moderate stenosis found on angiography in which the value of stenting was ambiguous.

iFR-SWEDEHEART, led by Matthias Götberg, MD, PhD (Lund University, Lund Sweden), is a registry-based RCT conducted almost entirely in Sweden, whereas DEFINE-FLAIR is a conventional RCT with patients in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, the United States, Australia, and Europe. Apart from these factors and differences in size—iFR-SWEDEHEART has 2,000 subjects and DEFINE-FLAIR 2,500—the trials are “almost identical. . . . All of the endpoints are the same,” Davies said.

“The real message,” he told TCTMD, “is that if these studies show no difference between the two [tests], effectively the big winner here should be the patient. Because it should make it easier and cheaper and nicer for patients to have their assessments made.” The big win, Davies added, would be an uptick in physiological assessment overall, not moving people from one type of technology to another.

This shift would allow cardiologists to “treat more people in a better way, how the guidelines are telling us to treat,” he predicted.

Why Choose iFR?

“Most physicians have seen the benefits of FFR to guide physiologic decision-making in the cath lab, [primarily] to determine whether or not a borderline or intermediate lesion is hemodynamically significant, which correlates with its ischemia-producing potential,” Gregg W. Stone, MD (Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY), told TCTMD. Above an FFR value of 0.80, patients can do well without revascularization, and at 0.80 and below, they do better with revascularization, he said. But “FFR like any other diagnostic test is not perfect, and it’s just one of the testing elements that go into the totality of the evidence that physicians have to consider when deciding whether revascularization is appropriate.”

Measuring FFR “takes time, and it takes experience and expertise,” Stone explained. “There are artifacts associated with FFR. And . . . perhaps most importantly it requires the establishment of a hyperemic state by infusion of adenosine, which is best given in an intravenous route. Many physicians will give it intracoronary, but to really ensure sustained and optimal hyperemia it’s best given intravenously.”

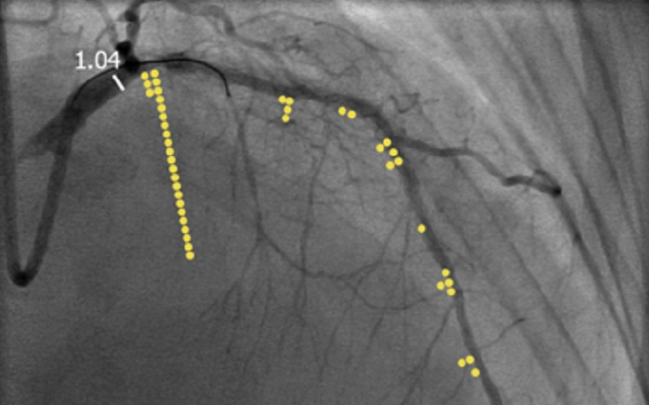

An advantage if iFR, Stone said, is that “you can pull the wire back and you get really an instantaneous measure along the coronary tree of what the iFR is. That is true of FFR as well but you have to do it under hyperemic conditions, whereas in iFR you’re doing it under resting conditions, so it’s a more stable situation.”

Regarding the potential for artifacts with FFR, Davies said that modality “doesn’t really work when you do pullbacks, because you have crosstalk between lesions,” he explained. During FFR measurement, “one lesion affects the physiologic measurements of another. So you can’t really ever interrogate things very well,” Davies noted. “Now this is a problem that doesn’t really exist with iFR just because the physics is a bit different. And so it means that we can independently interrogate one stenosis from another for the very first time.”

Stone agreed that this is a strength of iFR. “[W]hen you have tandem lesions or multiple diffuse disease in the coronary artery, it can be difficult to tell which lesions are contributing to the totality of the ischemic burden” and to know which need to be treated. “Do you need to treat the whole artery, four lesions, or just an area and then will that relieve ischemia? And that theoretically at least can be much more easily calculated with iFR than with FFR,” he explained.

Beyond this, there is the “not insubstantial cost of adenosine” and the potential for side effects that come with its use in FFR, Stone said. “So the concept of iFR is: can you derive the same quality of hemodynamic assessment of an intermediate coronary stenosis from a resting pressure differential across a lesion by measuring it in the so-called wave-free period of the cardiac cycle?”

Data from a “fair number” of nonrandomized studies “suggest that certainly at the outside ranges, there’s very good correlation between an abnormal FFR and an abnormal iFR, and between a normal FFR and a normal iFR,” Stone said. What’s less certain is how the two match up in a more intermediate range—eg, an FFR of 0.75-0.85—for which, “prior to these trials, FFR would be the gold standard.”

The new trials, he added, “are meant to level the playing field by showing true clinical noninferiority between the two.”

Neither Stone nor Davies noted any big downsides to iFR. Davies, for his part, estimated that around 4,500 cath labs around the world already use it. And while it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration about 1 year later than by European regulators, “adoption in the US is probably growing the fastest of anywhere in the world at the moment,” he reported.

Photo Credit: Adapted from: Davies J, iFR in Acute Coronary Syndromes, TCT 2016.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioDisclosures

- iFR-SWEDEHEART and DEFINE-FLAIR were funded by Philips Volcano.

- Davies reports grants and personal fees from Volcano Corporation and personal fees from Imperial College during the conduct of DEFINE-FLAIR, as well as grants and personal fees from Medtronic and ReCor Medical and grants from AstraZeneca.

- Stone reports serving as a consultant to St. Jude.

Comments