Thanks to COVID-19, Cardiology Fellows Gain Unexpected Skills but Risk Losing Others

Trading catheters for central lines, many fellows are stepping into roles they’d never imagined, while programs adapt.

For fellows, this time of year is usually filled with planning solo cases, finalizing contracts, and looking forward to the next stages of their careers.

This year is not like other years.

The COVID-19 pandemic has swept through cardiology training programs across the country, sending program directors scrambling to maintain some sense of a normal curriculum through virtual platforms. Fellows, on the other hand, are trading their planned education for shifts in ICU wards, all while doing their best to ensure safety and sanity.

“Initially, I was a little bit taken back,” Jay Mohan, DO, an interventional cardiology fellow at William Beaumont Hospital (Royal Oak, MI), told TCTMD. “I'm only in a 1-year fellowship right now, I'm PGY-7. It made me a little bit nervous to step away from the cath lab and go back into a role that I hadn’t been in for 5 years. . . . But then I quickly realized that was kind of a national trend and all elective procedures were canceled, and when I started on the MICU, I really noted that they needed my help.”

“I was super happy to be able to help,” said Elliott Miller, MD, a third-year general cardiology fellow at Yale University School of Medicine (New Haven, CT), who having previously completed a critical care fellowship has signed on as a COVID-19 ward attending. “It’s a world that we weren’t really trained for in medical school and a disease that no one knows too much about.”

Every fellow or program director that spoke with TCTMD expressed a similar sentiment—camaraderie and being there for each other and their patients—but all acknowledged a deviation away from traditional learning and teaching.

“I've been really heartened by the willingness and collaboration of all of our fellows,” said Edward Miller, MD, PhD, no relation to Elliott, who directs the general cardiology fellowship program at Yale University School of Medicine (New Haven, CT). “They've really taken to trying to support one another and support the overall mission, realizing that for this short period of time their personal goals for training and their careers are sort of taking a little bit of a back seat to the larger mission of the health system.”

Similarly, Douglas Drachman, MD, who directs the interventional cardiology fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA), told TCTMD that “we have had to rethink the way that we educate our trainees; using virtual platforms in place of in-person conferences is radically different than anything we’ve done before. Although there are many challenges, there are also many success stories in these evolving efforts that have been incredibly exciting.”

New Roles for Fellows

For Annapoorna Kini, MD, who directs the interventional cardiology fellowship program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, NY), being at the epicenter of the pandemic has meant drastic shifts in her team’s workflow. She told TCTMD that the dozen or so advanced cardiology fellows at her institution have been rotating through units filled with COVID-19 patients, spending some time in the cath lab, and participating in distance learning of coronary anatomy and hemodynamics through video conferencing or small group meetings.

For this short period of time their personal goals for training and their careers are sort of taking a little bit of a back seat to the larger mission of the health system. Edward Miller

“This is a group effort,” Kini said. “Interventional fellows are the backbone of the cath lab doing all the work for us with regard to the patient, of course with the nurse practitioners, doing pre- and postprocedural care. Right now with this crisis, since we are part of it, I think we all agreed that we've got to help our institution and our community. So, they all chipped in and they are okay to do that.”

While clinical work has shifted, academic priorities have continued full steam. “We were supposed to finish a practical handbook of interventional cardiology, so we are finishing the book chapters,” she said. Also, her team is “writing some review articles, finishing the manuscripts we had, writing grants, and . . . we have three to four apps we will be finishing during this COVID period.” Kini, already well-known for her work as a cardiology app developer, said she also plans to work on a book about yoga for interventionalists.

Edward Miller, who oversees 27 fellows in his program, said that while many of Yale’s more advanced fellows with experience in the ICU have been redeployed to help out in COVID-19 wards, others have been asked to stay at home. For the latter group, “I think conference attendance has gone up actually, because they've been less burdened with clinical care responsibilities and the distance learning platforms are so easy to use that it makes it a more efficient way for people's time,” he said, adding that faculty members have now had the time to conduct unique online learning opportunities for fellows. “Our echo lab has started to do a 4-5 PM every day teaching conference, which they weren't doing before when they're volumes were higher.”

Drachman said his fellows have been participating in a regional online lecture series with two other Boston hospitals. “This experience creates an amazing opportunity to cross-pollinate. We have the opportunity to see how clinicians address the same problems at neighboring institutions where the organizational cultures are different, technical and clinical approaches may differ, and we may learn from one another by sharing best practices,” he said.

Enough Training to Graduate?

At the same time, the curricula of cardiology training programs have typically been rigorously defined with little room for flexibility. Interventional fellows, specifically, need to have performed at least 250 therapeutic interventional cardiac procedures during their training year in order to be eligible to be certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine in interventional cardiology.

Despite the fact that she only has 1 year to ensure her interventional cardiology fellows are prepared, Michele Voeltz, MD, who directs the fellowship program at Henry Ford Health System (Detroit, MI), told TCTMD that “the depth and breadth of my fellows’ experience is enough that even if they didn't do another case, they would still have more than enough to graduate and be checked off on all of their primary skills.”

“I happen to be lucky,” she continued. “There are some other programs that have a harder time with numbers, and so if they're fellows are being retasked, their educations are going to suffer, which is unfortunate.”

The ACGME declined to provide comment for this story and directed TCTMD to their website, which provides recommendations for how institutions should be effectively operating graduate medical education at this time.

Interventional fellow Radha Mehta, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), who described her time working in the COVID-19 ICU as “quite a surreal experience,” said she is confident in her skills gained over 9 months of training to be able to graduate in June and start her new job at a hospital system in Seattle.

Everyone came together and everyone realized this isn't a problem of just pulmonary or internal medicine. This is a problem for the entire hospital, and the only way for us to get through it . . . is to work together as best as possible. Jay Mohan

“We face more challenges to ensure that we're going to be able to do our duties as doctors but also get enough volume to be trained well for the next stages of career that we're going to have,” she told TCTMD. “We are fortunate to be at Sinai because it's one of the largest volume programs, and so we have all met our numbers and we are prepared well. I feel confident that we are ready for the next stage, but most places may or may not be, depending on their volume.”

“In a sense, we are fortunate that this pandemic occurred relatively late in the academic year, which is a time when interventional cardiology fellows are often putting the ‘finishing touches’ on their year of experience,” Drachman said. Most interventional cardiology fellows spend this time focusing on self-improvement, he noted. “Interventional cardiologists continue to develop technical skills and clinical judgement well beyond the end of fellowship, but it's often during these final 3 months where fellows develop the skills to ask: ‘How do I stay current? How do I challenge myself to get to the next level of proficiency as I progress throughout my career?’ These insights and skills are what fellows are really focused on right now, and are learning a hundred times over in this extraordinary circumstance.”

While graduating fellows might be missing out on hands-on, case-based learning, they are gaining skills of the like Drachman said he has never seen before. “Leadership and administrative skills are not often directly taught in training programs,” he said. “They are often acquired in the background; but in the COVID-19 environment, our fellows are obtaining tremendous experience leading efforts to improve the systems around us, as we are all forced to reimagine our care paradigm as it evolves on a day-to-day basis.”

Drachman said he could see future fellowship curricula changed by this pandemic. “Through these challenging times, we value our fellows’ aptitude for the nonclinical competencies, including leadership skills, focus on systems improvement, and communicating with patients and providers in a complex environment. I envision that these skills will be invaluable for our fellows when they graduate,” he said. “I think we're going to graduate a very seasoned, wise, and capable class of fellows this June.”

Edward Miller agreed that his fellows have had “plenty of exposure and time to make up any live case type things that they're missing out on.” However, as the pandemic continues, several problems might arise.

“There’re going to be issues of onboarding and transitioning the new trainees and new fellows as our fellows graduate and our new ones come on in July. What's that going to look like? And that gets into recruitment season, too, which happens over the summer. How are we going to recruit the next class of fellows coming in during late summer and early fall? Those are going to be important concerns,” he said.

Senior fellows also might be worried, as many institutions have instituted hiring freezes and others with signed contracts have to contend with searching for a new place to live and moving during a pandemic.

Mohan, who plans to move with his wife and two young children over the summer for his job, said, “It's even harder to figure out when we can go check out apartments and are they even doing rental showings. I don't even know the process right now so we've kind of been delaying.”

Moreover, though he met his procedural numbers back in January, he said “what's a little bit concerning is I'm not starting my job until the end of August, so that means I potentially will be out of the cath lab for almost 5-6 months. Being in a procedural field, that's a little bit nerve-racking because you're going to get rusty pretty quick.”

Third-year general cardiology fellow Nidhi Madan, MD, MPH (Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL), plans to stay at her institution for an interventional cardiology year. “I’m excited,” she told TCTMD. “I'm hoping that this settles down by then and we start being able to do routine elective cases and even STEMIs.”

Mental and Physical Safety

Edward Miller has been relying on a national listserv of program directors for tips of how to keep his fellows engaged and safe. “One of the bigger challenges for all of us is to understand what the right balance is for what a trainee should be doing, what they should be exposed to,” he observed. “You don't want to put a fellow or trainee of any sort into a dangerous situation that you wouldn't put a senior physician into.”

Mostly, this whittles down to “trying to eliminate risky exposure situations,” he continued, giving the specific example of removing fellows from the echocardiography lab when transesophageal echos are being performed so that they are not exposed to potential infection sources coming from aspirated content in the air.

A recent paper published in Circulation argues that protecting fellows needs to be a priority. “Protect medical trainees on the COVID-19 front lines or do not send them in,” its authors write.

At his institution, Drachman said cardiology fellows are “preferentially” working in clinical units focused on patients with cardiovascular disease as well as COVID-19. “We've tried very deliberately throughout the hospital to engage the trainees and the faculty in areas that leverage the highest level of their training in order to optimize the care of patients with COVID-19,” he said.

Also, “there's been a very deliberate process for onboarding trainees and faculty as they commence providing care for patients with COVID-19,” he continued. “The onboarding curriculum covers critical and practical topics ranging from how to use [personal protective equipment (PPE)] most effectively, to the latest evidence-base for managing the advanced pulmonary disease and complex conditions associated with COVID-19.”

My first tweet ever - contains a few thoughts from NYC….to my fellow ACC Cardiology Fellowship Program Directors.I hope it is helpful to the community at large. #COVID19 @KBerlacher @ElaineWanMD @gabyweissman @DrJCheungEP @cardiacpolymath @ddefariayeh @erichorlick @DrHenryTran pic.twitter.com/XxRtF1JU55

— Harsimran Sachdeva Singh (@SimranSinghMD) March 29, 2020

For Mohan, who is now coming back to work after a 14-day quarantine period after having COVID-19-type symptoms, said his institution has properly limited the number of hours fellows are working with infected patients. “It's more because of the emotional toll it takes to be on the COVID units because you see how severe some of these patient’s courses are and a lot of them are dying alone because their families can't see them,” he said. “You're constantly on the phone with the families trying to make them understand: this is what the disease does.”

Even so, he said he’s excited to get back to work, “number one because my other interventional fellows are really burnt out at this point because I was sick, somebody else was on the ICU, so they're taking STEMI call almost every other day. So, I want to get back to help them. But I also want to get back to work so that I can kind of troubleshoot and work with the other fellows to maybe help with this pandemic and improving our patient outcomes.”

Kini acknowledged the mental effect this pandemic is having on all healthcare workers, but especially on trainees. “We just have to give them some psychological support, because this is something they've not seen. . . . As the senior people, we've got to help them to cope with it,” she said. “We're going through this pandemic which, I don't know, it's once in a lifetime. Not everybody goes through it. Somehow we became part of it.”

Many institutions are providing access to wellness hotlines, yoga and exercise programs, and free meals. But several people TCTMD spoke with said they are turning to chat groups on platforms like WhatsApp and virtual happy hours on Zoom to help them best decompress with colleagues and share information on treatment and proper PPE.

Implications for the Future

This crisis situation is ultimately one of team building and focusing on what truly matters, according to Edward Miller. “Hopefully, we're going to learn some things out of this, both at the delivery of medicine level as well as the educational level and how we can be effective. How do we improve our overall communication strategies? How do we make sure that we're building cohesive teams? And then, what's the right relationship between service and learning in the medical education environment?”

He said he tells his fellows that this will likely be a once-in-a-lifetime experience and “to understand that there are going to be feelings of unease. But hopefully in the end we're all going to come out of this stronger, more appreciative of what we have, and overall building a better healthcare system and cardiology education system in the long term.”

Madan agreed. “You feel so humble to be part of this community—that people are getting out there, helping patients, not caring about themselves,” she said. “I obviously never thought that I would experience a pandemic situation in my lifetime, . . . and I'm sure there will be some sad situations where we'll lose some of our people and people that we know, friends, families, or colleagues. But overall I think this will be a very humbling experience and that we should all come out of this very strong.”

Mehta said the pandemic is a “a historic milestone” for everyone living through it. “The challenging part is just the fear, one, of getting the disease and, second, of transmitting those diseases,” she explained, “because all of us have families that we go back home to and we don't want to make people around us sick as well.

“There is a lot of fear and negative emotions and uncertainty about everything, but I just want . . . the trainees who are my colleagues to not have a sense of despair at this time,” she continued. “We are all doing this together. We are all in the same boat, and we are all going to get through it similarly.”

“I think I will look back and I'll always remember it as being one of the most challenging times in my career, not just the medicine but also emotionally and on my family, just the amount of worry,” Mohan concluded. “I also will remember it in seeing how well everyone came together and everyone realized this isn't a problem of just pulmonary or internal medicine. This is a problem for the entire hospital and the only way for us to get through it and get through it efficiently and effectively is to work together as best as possible.”

“I think I’ll be proud that I volunteered for it,” Elliott Miller said. “And I think I’ll look back and really just kind of hope it never happens again.”

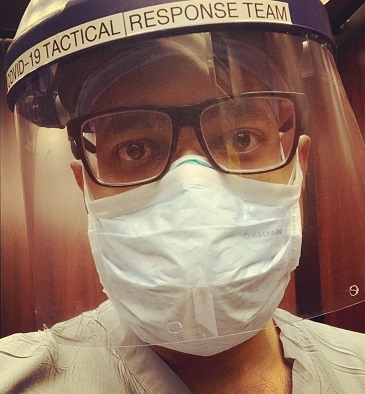

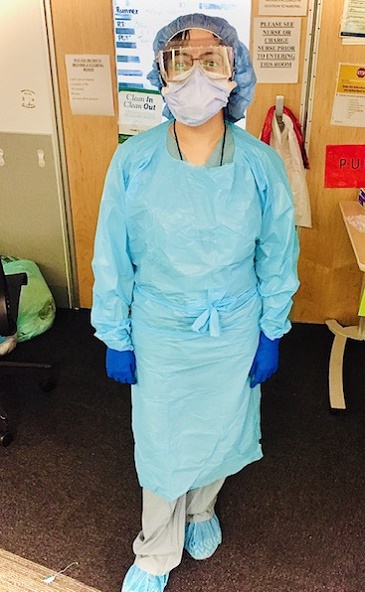

Photo Credits: Elliott Miller, MD; Michele Voeltz, MD; Jay Mohan, DO; Nidhi Madan, MD, MPH; and Emily Zern, MD.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full Bio

Comments