Timing of Mitral Surgery After Failed TEER Influences Outcomes

One-year mortality was highest when surgery was performed for aborted procedures, the CUTTING-EDGE registry shows.

MIAMI, FL—For patients who require mitral valve surgery after failed transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER), outcomes are worst when the initial procedure was attempted but unsuccessful, an analysis of the CUTTING-EDGE registry shows.

After these aborted cases, 1-year mortality was 47.7%, which was significantly higher than rates seen in patients who underwent initially successful TEER but required surgery for acute or delayed failures (28.9% and 26.7%, respectively; P = 0.032), Gilbert Tang, MD, MBA (Mount Sinai Health System, New York, NY), reported here at TVT 2021.

The heightened risk in the aborted group was driven primarily by worse tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and RV dysfunction, reflecting generally sicker patients, he said.

“Even though the TEER profile is safe based on the data out there, it’s important to avoid procedural complications and doing procedures on patients with right-sided heart failure and tricuspid regurgitation, because if it fails that leads to a higher mortality,” Tang told TCTMD.

CUTTING-EDGE Registry

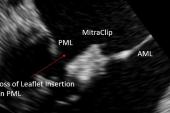

Though TEER has been performed for symptomatic moderate/severe or severe mitral regurgitation (MR) in over 100,000 patients worldwide—mostly with the MitraClip (Abbott)—there are times when it fails, resulting in the need for mitral surgery. The CUTTING-EDGE registry, which now includes 332 patients from 34 centers in Canada, Europe, and the United States, was created to provide insights into what happens in this particular scenario.

Previous analyses of the registry have shown that 1-year mortality is very high in patients who require surgery after failed TEER, particularly among those with moderate-or-worse TR before the transcatheter procedure.

In this new study, the investigators focus on the impact of the timing of TEER failure, dividing patients into three groups:

- Aborted (21.2%): TEER was attempted but unsuccessful, with surgery taking place during the same or a different hospitalization

- Acute (17.6%): TEER was completed, but surgery was required during the same hospital stay

- Delayed (61.2%): TEER was completed, but surgery was needed during a subsequent hospitalization

Overall, mean patient age was 73.8. At the time of TEER, the median STS PROM score was 4.0%, with about half of patients (51.3%) considered to have a low or intermediate surgical risk by the heart team. Most patients (59.0%) had primary or mixed MR, with the rest having secondary MR.

At the time of mitral surgery—which was performed for recurrent MR (33.5%), residual MR (28.7%), single-leaflet device attachment (25.1%), partial leaflet detachment (21.8%), or mitral stenosis (14.5%)—the median STS PROM score was 4.8%. The vast majority of patients (over 91%) had a MV replacement, as opposed to a repair, and many patients (42.2%) had concomitant tricuspid surgery.

Tang said surgical risk was relatively similar across the three timing groups. Patients in the aborted group were more likely to have mixed MR and had worse TR, RV dysfunction, and LVEF.

The data is accumulating rapidly that there is a price to pay for a failed MitraClip, particularly in degenerative disease. David Adams

Early clinical outcomes tended to be worse in patients who underwent surgery after aborted TEER procedures. In-hospital mortality rates were 22.9%, 13.8%, and 12.9% across the aborted, acute, and delayed groups (P = 0.13), with 30-day mortality rates of 26.6%, 15.8%, and 13.8%, respectively (P = 0.058). The gap between the aborted group and the other two groups became statistically significant at 1 year.

A concerning finding considering the overall safety of TEER, Tang said, is that the proportion of aborted cases did not change substantially over time. “You would expect that it would just come down significantly over time because of the learning curve issue and other things, but that has not been the case,” he said. “What I can infer is that we need to have experienced operators who can do this procedure safely to avoid having acute issues and having to abort the case and having a surgical intervention, because they don’t do well at 30 days and 1 year.”

That’s important to discuss with patients who are surgical candidates, especially those who are being seen at sites or by operators that are relatively inexperienced, Tang stressed. “What I mean is that if you’re operable, you need to be aware that maybe surgery itself is not an unreasonable alternative option for you rather than potentially doing a procedure, TEER, that . . . can lead to potential complications leading to surgical intervention.”

For patients who are at high or extreme surgical risk, it makes sense to consider TEER as the first option, Tang added, “but I think the operator has to give an optimal outcome to avoid any subsequent failure.”

Surgery After TEER Almost Always Replacement

Tang pointed out that when patients require surgery after TEER, it almost always means mitral valve replacement versus repair, which was seen in the CUTTING-EDGE registry and in a study using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database published earlier this year.

“Once the device is in, especially if it’s healed in the tissue, it’s really difficult to repair the valve because you don’t have a lot of tissue to bring back to restore the leaflet coaptation,” he explained. This is important because prior studies have shown that surgical valve replacement results in less-favorable outcomes compared with repair. “So in patients who are considered low or even intermediate surgical risk, who right now guidelines say should undergo surgical repair for primary MR, they should have a surgical repair in an experienced mitral center rather than doing TEER and then fail and have a replacement,” Tang said.

Commenting for TCTMD, David Adams, MD (Mount Sinai Health System), echoed that point, arguing for a more-durable surgical solution as the initial approach. A strategy that involves trying TEER first and then using surgery as a fallback is problematic, he indicated, because a failed TEER could destine patients who would have been candidates for surgical repair to get a higher-risk replacement instead.

“The data is accumulating rapidly there is an important price to pay for a failed TEER procedure,” Adams said. “Most patients will undergo an operation that carries increased risks according to this paper and your likelihood of valve replacement will be very high.”

An initial surgical solution may be particularly important in patients with severe TR and RV dysfunction, he suggested. “If you’re an intermediate-risk patient and you have RV dysfunction and severe TR with severe MR, you need to have an operation to address both valves,” he said. “I don’t think you can treat double valve disease with RV dysfunction with an isolated mitral valve operation.”

Adams acknowledged that surgery is not as appealing to patients as a less-invasive intervention, but said that shouldn’t necessarily drive what treatments are offered by the heart team. He pointed to a 2019 analysis in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery showing that even though 1-year survival was similar between patients treated with MitraClip and those treated with surgery, a big advantage was seen for surgery over longer-term follow-up.

“The focus shouldn’t be on how fast did the patient recover and stay in the hospital,” he said. “The focus for mitral disease in low- and intermediate-risk patients with degenerative disease should be on did we extend your life expectancy if possible, did we help you feel better, and did we restore you back to your normal mitral valve function with mild-or-less MR.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Tang GHL. Impact of timing of surgery on outcomes of mitral valve surgery after edge-to-edge transcatheter mitral repair: results from the CUTTING-EDGE registry. Presented at: TVT 2021. July 20, 2021.

Disclosures

- Tang reports being a physician proctor for Medtronic; a consultant to Abbott, Medtronic, and NeoChord; and a physician advisory board member for Abbott and JenaValve.

- Adams reports having royalties/intellectual property rights from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic, as well as grant support/research contracts from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, and NeoChord, through his institution.

Comments