When a Pacemaker Lead Complicates Transcatheter Tricuspid Replacement: New Insights

Longer-term data and close follow-up are key, but experts agree the procedure can be confidently performed by operators.

For patients with transvenous pacemaker leads, transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR) can be performed safely with a low risk for periprocedural complications, according to a new observational study.

Among patients who have previously undergone tricuspid valve surgery—which itself puts patients at high risk for needing a permanent pacemaker—who require reintervention, the transcatheter approach has gained traction in recent years. But little evidence exists regarding its long-term safety and efficacy, especially in patients with pacemakers in place.

Lead author Jason H. Anderson, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), told TCTMD that they designed their study to give some guidance to operators, because until now “it's basically been a case-by-case scenario where each case is just determined by the implanting physician and the team taking care of that patient.”

Although longer follow-up is essential to understand whether patients with transvenous pacing leads who undergo TTVR are at risk for accelerated valve dysfunction, “there is no obvious reason for concern on the basis of the evidence in this preliminary experience,” the researchers write .

“We have to be careful to say with any degree of certainty that we have seen the endpoint,” Anderson clarified. “One of the things with pacemaker leads themselves is that we could be setting the lead up for ongoing fracture and loss of integrity at the site of the implant, because there's now basically a flexion point where it's outside that stent frame. So the only way we can really see the long-term effects is [by looking at] upwards of 5-10 years post-valve implant to see how these leads act and how they behave and whether or not they're at higher risk for fracture during follow-up.”

Can Öztürk, MD, Johanna Vogelhuber, MD, and Georg Nickenig, MD (all from University Hospital Bonn, Germany), write in an accompanying editorial that this study brings good news in terms of mortality, which was “only” about 15% at 2 years despite a high incidence of morbidity. “Although accurate information on periprocedural mortality is lacking, it may be speculated that the complication rate may be lower with catheter-based redo TV procedures compared with the surgical open-heart approach,” they write. “In any event, it has to be stated that this post hoc analysis is far from proving the superiority of a catheter-based therapy over surgical treatment. This would require a prospective randomized study.”

Few Complications

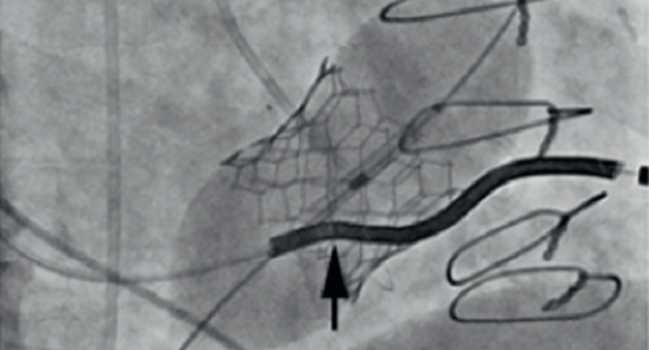

For the study, published online last week ahead of print in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, Anderson and colleagues included 329 patients from the VIVID registry who underwent TTVR with a SAPIEN (57%; Edwards Lifesciences) or Melody (43%; Medtronic) device for tricuspid valve dysfunction, defined as moderate or greater TV regurgitation on echocardiography or significant TV stenosis equating to a mean diastolic Doppler gradient ≥ 10 mm Hg despite previous tricuspid valve repair or replacement surgery. Most patients received a stented surgical bioprosthetic valve (91%) with the remainder being implanted with a transcatheter valve (1%), annuloplasty ring-supported autograft or stentless replacement valve (1%), or previously repaired tricuspid valve (7%). Overall, 39% already had pacing systems implanted—70 with epicardial leads and 58 with transvenous leads.

The only way we can really see the long-term effects is [by looking at] upwards of 5-10 years post-valve implant to see how these leads act and how they behave and whether or not they're at higher risk for fracture during follow-up. Jason H. Anderson

Of the 31 patients with pacing leads that passed through their tricuspid valve, three had their right ventricular (RV) lead removed before TTVR and the rest had their RV lead entrapped between the transcatheter bioprosthesis and the surgical valve (n = 22) or the native or repaired tricuspid valve (n = 6). Over a median follow-up of 15.2 months, three patients whose procedures resulted in entrapped RV leads (10.7%) reported complications including two lead failures and one lead fracture.

Over a median follow-up of 17.2 months there were no significant differences in the cumulative endpoint of death, TV reintervention, and TV dysfunction between patients with and without pacing leads or entrapped RV leads.

Promising, More Attractive Than Surgery

The researchers write that this is the largest analysis of its kind to date and should help ensure confidence in operators looking to perform TTVR on patients with transvenous pacing leads. Nonetheless, operators should be cautious of the potential for lead dislodgement, “especially in patients who are pacemaker dependent, in whom temporary pacing systems or placement of new transvenous lead may be necessary,” they write.

And while no valvular complications were identified in this cohort, future research with longer follow-up will be needed to determine if these patients become higher risk for accelerated valve dysfunction, the authors note.

“Management of pacing leads is an important concept in the overall care of patients with TV disease, as evidenced by the large number of TTVR candidates with pacemaker systems in our study, representing 39% of the initial intention-to-treat cohort,” they write, adding that although various management strategies have been pursued, some of which may add morbidity risk, no clear winner has been determined.

The study findings offer an opportunity for better preprocedural TTVR planning, Anderson and colleagues say. “One could argue that increased surveillance for changes in lead threshold and impedance may need to be adopted after TTVR with lead entrapment,” they write. “Overall mortality during follow-up, however, was unrelated to the TTVR procedure or RV pacing lead failure, thus providing further support for the safety of this technique, especially in a relatively fragile patient population.”

The editorialists add that the “worrisome message” of the results is that upwards of 10% of the patients experience lead failure induced by the valve procedure. “One could argue that these patients do not have many or any other treatment options and that a 10% risk should be considered as acceptable,” they write. “On the other hand, it appears to be of utmost importance to assess symptoms and their causality as well as comorbidities preprocedurally.

Öztürk and colleagues also argue the need for longer-term follow-up to assess valve complications.

“Late-onset pacing lead damage cannot be excluded from this study, and the pacing lead complication rate may increase subsequently,” they write. “Another caveat is that we do not know the actual morbidity and mortality in those patients who experienced pacing lead dysfunction.”

Overall, “in this highly morbid patient group, redo TTVR appears promising and more attractive than surgical open-heart procedures,” they conclude. Still, “innovative further developments” in tricuspid valve surgery like beating-heart and minimally invasive procedures will also need to be considered by the heart team.

Photo Credit: J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. Central Illustration (adapted).

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Anderson JH, McElhinney DB, Aboulhosn J, et al. Management and outcomes of transvenous pacing leads in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Öztürk C, Vogelhuber J, Nickenig G. Challenge with cardiac cables. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Anderson, Öztürk, Vogelhuber, and Nickenig report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments