Adapted D-Dimer Thresholds Safe, Efficient for Acute PE Diagnosis

Multiple strategies could work, but a review proposes using “one strategy as standard of care in each individual hospital.”

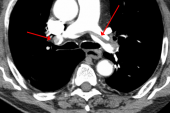

Use of clinical decision rules in conjunction with D-dimer thresholds adjusted higher based on either age or pretest probability is acceptably safe for ruling out acute pulmonary embolism (PE) without the need for imaging—and more efficient than using a fixed cutoff—even in select high-risk patients, a review and meta-analysis indicates.

Overall, the Wells rule, the revised Geneva score, and the YEARS algorithm were most efficient (based on the proportion of patients with PE ruled out without the use of imaging) when combined with D-dimer thresholds that varied based on clinical pretest probability, and they were least efficient with a fixed cutoff of 500 µg/L.

“The relative efficiency increase with these variable D-dimer thresholds was highest in the subgroups of elderly patients, patients with cancer, and patients with a previous VTE [venous thromboembolism],” researchers led by Milou Stals, MD (Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands), report.

These strategies employing adapted D-dimer thresholds also had the highest predicted failure rates (a measure of missed VTE events), although that was not enough to offset the gains in efficiency, Stals told TCTMD, noting that the failure rates were likely overestimated.

She said that failure rates are expected to be higher in certain patient subgroups at greater risk for VTE, like those evaluated in the study. Failure rates also were likely inflated by verification bias—with researchers finding more isolated subsegmental PE cases, which don’t necessarily require treatment, due to increased use of imaging—and misclassification bias stemming from patients in these subgroups being more likely to die during follow-up and to have their deaths incorrectly attributed to recurrent PE.

Clinicians can use the tables in the paper, published online Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine, to choose a diagnostic strategy that best balances safety and efficiency, Stals said. “But I think the most important thing is to incorporate one strategy per individual hospital, instead of choosing a particular strategy based on patient characteristics, because adherence to a diagnostic strategy is key to really establish good performance of these strategies,” she advised. “So we propose incorporating one strategy as standard of care in each individual hospital, and based on these results, we support the use of strategies with adapted D-dimer thresholds.”

Performance in High-risk Subgroups

Over the past few decades, many diagnostic strategies for suspected PE—consisting of clinical decision rules combined with D-dimer testing—have been developed and validated in general patient populations, Stals explained. But there has been a lack of validation within specific high-risk subgroups—such as older patients and those with cancer, for example—that have been underrepresented in the clinical studies. So, Stals said, “we don’t know how these strategies really perform in these patient subgroups, which is important because we want to use them in clinical practice as they can reduce the need for imaging tests.” Avoiding imaging can minimize exposure to radiation and contrast media, reduce costs, and improve efficiency in busy clinical settings, she and her colleagues note.

In the current analysis, Stals et al examined the safety and efficiency of various diagnostic strategies incorporating widely used clinical decision rules—specifically, the Wells rule, the revised Geneva score, and the YEARS algorithm—and D-dimer testing with either fixed or adapted thresholds, with a particular focus on three high-risk subgroups—older patients, those with active cancer, and those with prior VTE.

The pooled patient-level data on 20,553 patients with suspected PE (median age 58 years; 59% women) from 16 studies.

The diagnostic strategies that were most efficient were those that used D-dimer cutoffs dependent on either pretest probability or age, with an advantage for those using pretest probability. Efficiency was highest in patients younger than 40. It was lowest in patients 80 and older and in those with active cancer, although performance improved “considerably” in these subgroups when adapted D-dimer thresholds were employed.

Predicted failure rates were highest for approaches incorporating adapted D-dimer thresholds, ranging from 2% to 4% across the predefined patient subgroups.

Pointing to several potential reasons for inflated failure rates in these high-risk groups, the authors say, “We do not believe that there are safety concerns with the available strategies in the patient subgroups included in our analyses, notwithstanding the observation that some uncertainty and heterogeneity of the failure rate remains, especially in the oldest patients. Thus, given this uncertainty, and acknowledging that patients in the subgroups studied in our analysis also remain at high risk for new thrombotic events during follow-up, a reassessment should be initiated at a relatively low threshold if symptoms progress or persist.”

Addressing potential differences between strategies evaluated in the study, the authors say that the choice comes down to local preference and experience. “We’re not really pushing one over the other because there are no randomized trials suggesting one is better than the other,” senior author Erik Klok, MD, PhD (Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands), told TCTMD.

Randomized trials are still needed in this area, and Klok noted that his group is conducting the Hydra study, which is comparing the safety and efficiency of the YEARS algorithm with CT pulmonary angiography in patients with cancer and suspected PE.

Ready for Prime Time?

Commenting for TCTMD, Daniel Brotman, MD (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD), who wrote an accompanying editorial, said this analysis is important because it pools enough patient-level data from multiple studies to provide information on the utility of these diagnostic approaches in patient subgroups that have not been well represented in any single study.

And the findings indicate that use of higher D-dimer thresholds in these high-risk subgroups “is ready for prime time,” he said. “I think there’s always going to be exceptions to general rules, but I think that higher thresholds are certainly defensible in any of these higher-risk groups of patients.”

The approach is supported by prior data showing that D-dimer has prognostic value independent of its diagnostic value, Brotman explained. “So even if we are missing the occasional small pulmonary embolism [using higher cutoffs], it’s likely that the patients in whom we are missing small PEs are going to have a better prognosis than patients who have larger events. . . . In other words, you don’t miss very many PEs and the ones you do miss are likely to be pretty small rather than ones that are going to prove fatal to patients.”

When it comes to use of higher D-dimer thresholds for ruling out PE, “the biggest hesitation I have in making that recommendation is that for many of these patients it’s so easy to access CT angiography that the overall incremental cost is not that high,” Brotman said. “I think if a D-dimer test result [can be obtained] quickly and you’re in a clinic and you don’t have access at that time to a CT scan, that’s a pretty useful scenario” for use of adapted D-dimer thresholds to rule out PE, he explained. “I think it may be less useful in an emergency department where you have such easy access to CT imaging that you can just do it.”

In addition, if physicians are worried about using CT because of borderline renal function in a patient, “I think that you can justify stopping at the D-dimer if it’s in between the standard threshold and the elevated threshold,” Brotman advised.

Overall, Brotman said, “if you have been hesitant to adopt higher D-dimer thresholds in patients who were underrepresented in clinical trials—such as the elderly, such as patients with malignancy—this is a good paper to review to give you some confidence that you can probably use those higher thresholds across the board.

“Obviously there’s going to continue to be room for clinical judgment,” he continued, “but I think that you are adhering to the standard of care in not getting CT imaging [to formally rule out PE] in a patient who according to the age-adjusted D-dimer level or the YEARS algorithm is in that intermediate range.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Stals MAM, Takada T, Kraaijpoel N, et al. Safety and efficacy of diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism in clinically relevant patient subgroups: a systematic review and individual-patient data meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Brotman DJ. Higher D-dimer thresholds for excluding pulmonary embolism: no free lunch? Ann Intern Med. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Research Council.

- Klok reports research grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, Actelion, the Dutch Heart Foundation, and the Dutch Thrombosis Association, all outside the submitted work.

- Stals reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Brotman reports investigator-initiated grant funding to his institution for a study on VTE treatment in patients with renal failure.

Comments