The Case for Collateralization: CABG’s Mechanism for Survival in Stable CAD Underappreciated by Patients

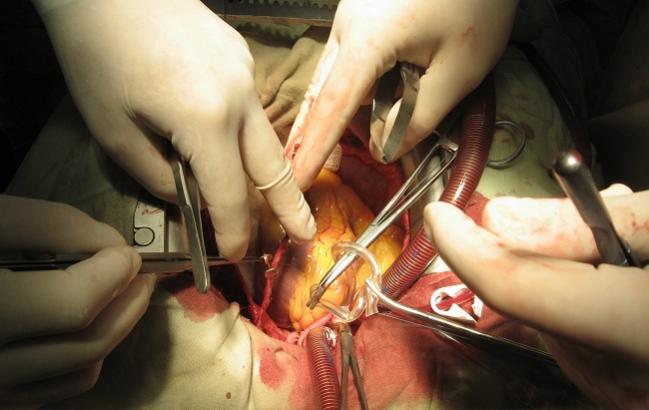

In a review paper, researchers argue that surgical protection against MI may be life-prolonging and should be communicated as such to patients.

Although PCI and CABG are both valid revascularization strategies for patients with stable CAD, surgical collateralization may provide the best survival benefit and protection against new MI, according to a newly published review. Its authors suggest that recognizing the differences between the two strategies and explaining them fully to patients could alter current management approaches.

“Patients should be informed that they can be treated for their symptoms with PCI and that they can obtain revascularization plus protection against new infarction from CABG,” write Torsten Doenst, MD, PhD (University Hospital Jena, Germany), and colleagues. They maintain that the terminology needs to change when communicating clinical options to patients.

“CABG should no longer be considered a method of revascularization alone,” Doenst et al continue. “It adds a mechanism of myocardial protection that explains its ability to prolong life (which may be less detectable if the disease is not associated with greater natural risk). Consenting patients, which is already suboptimal if it comes to addressing CABG as a revascularization option for CAD treatment, needs to change.”

In the review, published online February 25, 2019, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Doenst and colleagues point out that all comparisons of CABG to PCI or medical therapy that have demonstrated survival effects of CABG also showed a reduction in infarcts. Given that most infarcts are generated by non-flow-limiting stenoses, and that PCI is aimed at treating flow-limiting lesions, CABG offers a broader option for improving flow distal to vessel occlusions, they say.

“In addition, the majority of deaths in this patient population are due to cardiac reasons, mainly AMI. Thus, protection against infarction may be an underappreciated mechanism, although it had been suggested previously. Because native collateralization protects from infarction of acute vessel occlusion, CABG may do the same surgically,” the co-authors observe. Even still, they acknowledge that the available data suggest that CABG may reduce infarcts and cardiovascular death up to a maximum of 50%, leaving plenty of room for other causes of cardiovascular mortality.

In an email, Doenst said establishing a causal relationship in humans between the collateralization effect and survival is practically impossible. But the review paper “puts together circumstantial evidence, which however is strong and very plausible,” he added.

“It's an excellent theory, which I also believe is probably true,” commented Gregg Stone, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), in an interview with TCTMD.

“The reason there seems to be a lower rate of late myocardial infarctions in many patients after bypass surgery is that PCI is a 'spot treatment.' It only treats that individual area of atherosclerosis, whereas surgery usually bypasses 5 to 6 centimeters of the coronary tree and therefore may be protective not only against the severe lesion that it's bypassing, but also [against] other mild diffuse areas of atherosclerosis that could go on to rupture or thrombose in the future,” Stone noted. While it has never been demonstrated that that is the cause of the reduction in late MI with bypass versus PCI, he added, ongoing angiographic studies may eventually prove it to be true.

Data vs Patient Preference

But for Stone, the overarching issue that should not be lost is patient-centered, shared decision-making.

“If you just look at the data it would suggest that in patients with extensive coronary disease and perhaps diabetes, there appears to be a survival advantage for surgery compared with PCI, whereas in patients without extensive disease and without diabetes, the survival seems to be roughly comparable. But at the same time, almost all studies show a higher risk of stroke with surgical revascularization compared to PCI,” he said. “For many patients, the risk of stroke is as or even more concerning than the risk of dying.”

While everybody would like a once-size-fits-all declaration, it's much more nuanced and complex than that. Gregg Stone

To TCTMD, Doenst noted that PCI “has about the same mortality at 30 days as CABG, despite the big difference in invasiveness. So, it is not as harmless as it is always referred to.”

Furthermore, Doenst said personal preference does not change facts. “The key in the future will be the assessment of risk of infarction. We are not really good at that,” he noted. “So, if a CAD patient has some isolated flow-limiting stenoses (which convey a certain risk of infarction) stenting them will reduce this risk (at the cost of stent thrombosis and restenosis; this may actually be the explanation for the recent FAME 2 outcomes), and if there is only little extra risk from limited additional CAD with non-flow limiting stenosis, CABG will not be better. However, if in addition to the flow-limiting stenoses, there are more plaques that may cause infarction, CABG should be better for the collateralization effect (ie, infarct protection).”

Stone agreed that patients need to be given the full picture of all of the advantages and disadvantages with each type of revascularization procedure so they can make an informed decision.

"You have to have a relatively sophisticated discussion,” he observed. “While everybody would like a once-size-fits-all declaration, it's much more nuanced and complex than that."

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Doenst T, Haverich A, Serruys P, et al. PCI and CABG for treating stable coronary artery disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:964-976.

Disclosures

- Doenst reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Stone reports relationships with multiple pharmaceutical and device manufacturers.

Comments