Failure of ‘Jailed’ CIED Leads Not Uncommon After TTVR: TRIPLACE

The findings highlight the importance of having an EP versed in lead management on the heart valve team, one expert says.

NEW YORK, NY—Transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR) is safe and effective in patients who have severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and preexisting leads from implanted cardiac devices, but problems with the leads can emerge in subsequent months, findings from the TRIPLACE registry affirm.

Over a median follow-up of about 6 months after TTVR, right ventricular lead failure occurred in 5.9% of patients, Bryan Traynor, MB, BCh, BAO (St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada), reported here at New York Valves 2025.

“Within that lead failure group, there were no catastrophic events,” Traynor told TCTMD, noting that these events mostly stemmed from a change in lead function parameters detected on routine follow-up that led to additional leads or devices being put in.

“That being said, obviously there is a significant percentage there of lead failures that has to be taken into account,” he added.

According to Laurence Epstein, MD (North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY), a cardiac electrophysiologist (EP), “it’s really important that somebody is actually looking at this.”

There’s a lot of excitement in the tricuspid valve space, he told TCTMD, adding that structural interventionalists have historically thought that jailing leads from cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) during procedures isn’t a problem. EPs, on the other hand, have always figured it could pose trouble.

“Now there’s more and more data growing that there is an issue, and things like the TRIPLACE registry are going to be really important to fill in our knowledge gaps,” Epstein said. “It’s great to hear that this is being done and that we’re going to continue to get results that hopefully will help guide clinical care.”

The TRIPLACE Registry

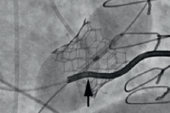

Transcatheter interventions for TR represent a rapidly evolving landscape, Traynor said, and in recent years, there has been growing interest in how to manage patients with CIED leads across the tricuspid valve. Roughly one-third of patients undergoing TTVR have preexisting device leads, and although extracting them is an option, they commonly will be left in place and become “jailed”—crushed between the device and the native tricuspid annulus.

There continues to be debate about how these leads perform after the interventions and what impact they have on the success of the tricuspid procedures. There is “pretty limited” data to inform clinical decision-making, Traynor said.

To help provide fodder for those discussions, he presented data from TRIPLACE, an investigator-initiated, multicenter, international registry that includes patients who underwent orthotopic TTVR for significant native TR who were not participants in active clinical trials. The current analysis included 379 patients (mean age 77.8 years; 65.7% women) with severe TR who underwent TTVR with various systems between 2018 and 2025. Of those, 26.6% had a preexisting CIED lead across the tricuspid valve.

In general, procedural echocardiographic and clinical outcomes were similar regardless of the presence of a jailed CIED lead, although patients with a lead in place were less likely to require temporary pacing (0.99% vs 5.8%; P = 0.049).

At 30 days, there were no differences between the patients with and without leads in terms of mortality (3.96% vs 6.1%) or NYHA class I/II symptoms (77.1% vs 83.9%; P = NS for both).

An electrophysiologist versed in lead management should be a part of the heart valve team. Laurence Epstein

Through longer-term follow-up (median 181 days for those with jailed leads and 262 days for others), the two groups had similar rates of mortality, heart failure hospitalization, new permanent pacemaker implantation, and TTVR thrombosis and endocarditis, as well as similar TR severity.

The group with jailed leads, however, was more likely to have residual TR that was severe or greater (9.3% vs 3.8%; P = 0.036) and to undergo a repeat tricuspid intervention (5.9% vs 1.8%; P = 0.034). Those patients also were less likely to have severe bleeding (1.98% vs 8.6%; P = 0.023), although Traynor said that finding is likely spurious.

In the patients with CIED leads in place at the time of TTVR, in addition to the cases of confirmed lead failure, new permanent pacemaker implantation or reprogramming of a current pacemaker occurred in 6.9%.

Among patients with jailed leads and sufficient data, there was an increase in threshold from baseline to follow-up, but no significant changes in other lead parameters.

A Role for EPs on Heart Valve Teams

Epstein said the rate of lead failure observed in this study at a median of 6 months was “really concerning,” adding that “leads fail all on their own, but usually they fail over 10 or 20 years. If you look at lead survival on a pacemaker lead, for example, the failure rate at 10 years is maybe 3% or 4%. So 6% at 6 months is quite significant.”

Something else to consider is that a small proportion of patients have lead-related TR that will improve to the point that a tricuspid intervention is no longer necessary if the lead is extracted, said Epstein. Many physicians, he added, overestimate the risks of lead extraction. For example, data suggests that 30-day mortality is about 2.3% with TAVR, more than 3% with TTVR, but just 0.08% with lead extraction.

Part of his job, Epstein said, “is to have people understand that in experienced hands—not anybody just pulling these out—lead extraction could be safe and effective, and you may prevent the need for the valve intervention in the first place. And even if you don’t, you make the procedure simpler because the lead’s not there and you obviate the risk of what happens if you jail a lead.”

A challenge Epstein highlighted is that interventional cardiologists and EPs haven’t always been talking to each other when it comes to managing patients undergoing tricuspid procedures, although that’s been changing in recent years.

“If you really want to do what’s right for the patient, you find a local regional center of excellence where you can send the patient to get the lead dealt with. They send them back and then you can do your intervention,” he said. “I am hopeful that with more data we can change people’s minds.”

New US guidelines are coming on lead management, but in the meantime, Epstein said, “certainly an electrophysiologist versed in lead management should be a part of the heart valve team.” That could be important even for patients who don’t have CIED leads, he added, noting that the incidence of heart block after TAVI and TTVR, for instance, is not insignificant. “Really the collaboration is what leads to the best care for patients.”

Traynor agreed that it’s important to get interventional cardiologists and EPs talking to each other about these cases. “Having an alternative pacing strategy in place prior to doing the procedure and making sure that the follow-up in terms of pacemaker or lead checks occurs at regular intervals after the procedure are absolutely vital,” he said. “In the modern era, a transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention program should certainly have EP involvement at the very least.”

He noted that lead extraction is not a benign procedure and should be performed on “probably a case-by-case basis, but definitely a robust heart team discussion is the first place to start.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Traynor BP. Transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device endocardial leads. Presented at: New York Valves 2025. June 25, 2025. New York, NY.

Disclosures

- Traynor reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments