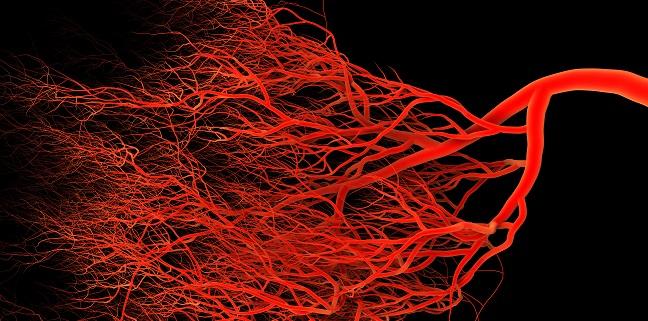

Microvascular Disease Quadruples Risk of Leg Amputation

At minimum, a diagnosis of microvascular disease warrants a check on the health of the patient’s feet, say researchers.

The presence of microvascular disease anywhere in the body significantly increases the risk for leg amputation in ensuing decade, results of a large study of US veterans shows. Additionally, in patients with PAD, having microvascular diseases such as retinopathy and neuropathy dramatically compounds lower-limb risk.

Over a median follow-up of 9.3 years, microvascular disease—even after adjustment for demographic characteristics, CVD risk factors, and other potential confounders—was associated with a nearly fourfold increased risk of leg amputation, while a diagnosis of PAD alone was linked to a 14-fold rise in amputation rate.

“If you had both peripheral artery disease and microvascular disease, compared with people without either of those things, you had 23 times the risk of amputation over 10 years,” lead author Joshua A. Beckman, MD (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN), told TCTMD. “It’s literally like putting a match to the gas.”

In their paper, published online July 8, 2019, ahead of print in Circulation, Beckman and colleagues say the findings point to microvascular disease playing “an important and independent role” in conditions that increase the risk of amputation. To TCTMD, Beckman added that the data help draw a picture of these diseases as “one big phenotype” suggestive of a systemic phenomenon.

Higher Risk No Matter the Microvascular Disease Location

The study comprised data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study on 125,674 veterans, predominately men, with no prior amputation history. Microvascular disease accounted for 18% of all amputations, 21% of foot amputations, 15% of below-the-knee amputations, and 6% of above-the-knee amputations. The combination of microvascular disease and PAD accounted for 45% of all amputations and was associated with the highest percentage of amputations at all limb levels. Beckman and colleagues also found that patients with microvascular disease were more likely to have a below-the-ankle amputation, while those with PAD were more likely to have both below- and above-the-knee amputations.

In subgroup analyses of diabetic patients, microvascular disease alone was associated with a 3.1-fold increased risk of amputation and PAD alone with a 7.9-fold increased risk. The combination of the two in diabetic patients conferred a 15.9-fold increased risk of amputation.

At a minimum, if you have microvascular disease in any location, you need to start warning patients to pay attention to their feet. Joshua Beckman

MACE occurred at a rate of 24 events per 1,000 person-years over the course of the study period. “In contrast to the strong association between microvascular disease and amputation, we describe a more modest relationship for myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, and death,” Beckman and colleagues write.

The findings have direct implications for clinical practice, said Beckman.

“At a minimum, if you have microvascular disease in any location, you need to start warning patients to pay attention to their feet. One out of six amputations in this study came from the group that only had microvascular disease,” he noted. Beckman also stressed that clinicians should not be concerned only about their diabetic patients, because the impact of microvascular disease seen here was the same for everyone. “Diabetes is just a very common way to get microvascular disease, but it’s not the only one,” he added.

In the paper, the researchers note that while they cannot exclude the possibility that some patients may have had undiagnosed diabetes, “the likelihood that undiagnosed diabetes contributes significantly to the findings in our nondiabetic population is modest.”

Beckman said his advice for physicians is that microvascular disease of any type, even in the eye, "should mandate taking off the shoes and socks. You have to look at the feet.”

For specialists or others who might not be comfortable with foot exams, his advice was simple: “If someone has a sore on their foot it should be at least 50% better by 2 weeks. If it's not, that’s a signal to send them to a podiatrist, or to a cardiovascular specialist if you examine them and there are no pulses. We can do a lot in terms of prevention by finding things early and by making sure that people get wound care, foot off-loading, or—if they need it—revascularization.”

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Beckman J, Duncan M, Damrauer S, et al. Microvascular disease, peripheral artery disease and amputation. Circulation. 2019;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was funded by the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network in Vascular Disease and the US Department of Veterans Affairs

- Beckman reports consulting for Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, Merck, Sanofi, Antidote Pharmaceutical, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and serving on data safety monitoring committees for Bayer and Novartis.

Comments