PET Imaging Detects Degeneration After TAVI as Well as Surgical, Native Valves

The findings also show disease progression in native valves after TAVI, suggesting an “active process,” with research implications.

At 5 year follow-up, 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF) positron emission tomography (PET) imaging appears to offer similar insights into valve degeneration following TAVI as it does for native and surgically implanted bioprosthetic valves and shows potential for predicting subsequent dysfunction.

Results of the FAABULOUS 2 study also offer some reassurances that subclinical bioprosthetic valve degeneration is no worse following TAVI than it is for surgically implanted valves, raising the possibility that 18F-NaF PET may hold some advantages over other imaging modalities for screening for valve deterioration following TAVI.

Previous studies have shown the advantages of 18F-NaF PET imaging for identifying calcification and vascular injury across a wide spectrum of cardiovascular disease, which can in turn predict future clinical events. Given the lack of long-term hemodynamic data in TAVI and concerns that crimping the bioprosthetic valves in order to deliver the devices might lead to valve degeneration, this kind of imaging has held promise for identifying earlier markers of valve durability.

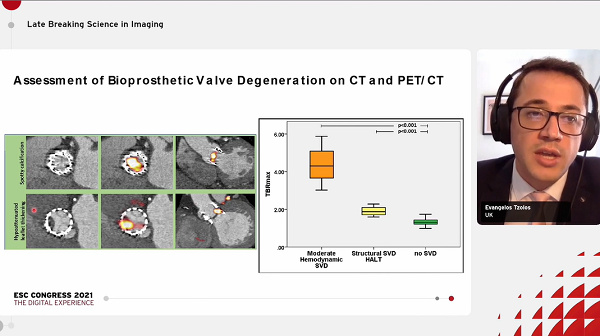

Evangelos Tzolos, MD (University of Edinburgh, Scotland), who presented the findings during the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2021, told TCTMD he could see this kind of imaging being used in both TAVI and SAVR at 5 years after the procedures “to distinguish patients at risk compared to patients not at any significant risk of failure of the valve.” The intensity of subsequent follow-up could then be planned accordingly, he added.

An additional surprising finding of the study, which at this point has more implications for research than for practice, Tzolos said, was the discovery that aortic stenosis continues to progress even after TAVI. During his presentation, he said he expected to see high uptake of sodium fluoride on PET imaging by about 1 month after TAVI due to “squeezing,” and hence immobilization, of the native valves but that it would decline thereafter. “To our surprise, that wasn’t the case,” he said. “Five years later, we can see that the uptake was even higher. So, it seems that native aortic valve disease is a more active disease: that after it starts, it’s an escalation, a cascade that doesn’t stop, and it doesn’t require any further impulse or any further injury to the valve.”

Because of this, “we need to think very carefully if we want to treat these patients medically,” and that further studies need to determine a more specific target to stop calcification progression,” Tzolos continued. “This is an active process. Once it starts it seems that it doesn’t stop.”

Even after TAVI or surgery, with a starting time point still unknown, she added, “you will have degeneration of the valve.”

FAABULOUS 2 Results

For the FAABULOUS 2 study, simultaneously published in Circulation, Tzolos along with lead author Jacek Kwiecinski, MD, PhD (Institute of Cardiology, Warsaw, Poland), and colleagues included 47 TAVI patients (53% with balloon-expandable prostheses) from three centers who underwent baseline echocardiography, CT angiography, and 18F-NaF PET scanning. PET/CT scanning was repeated again at 1 month (n = 9), 2 years (n = 22), or 5 years (n = 16) after valve implantation, and all patients underwent serial echocardiography.

This is an active process. Once it starts it seems that it doesn’t stop. Evangelos Tzolos

The researchers observed a “modest positive” correlation between 18F-NaF uptake outside the TAVI valves and time from implantation (P = 0.023), with uptake being highest in those with scans taken at 5 years. Further, compared with 51 age-matched patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement, uptake was similar for the TAVI patients (target to background ratio 1.3 vs 1.3; P = 0.27).

Evidence of valve degeneration at baseline were similar for TAVI and surgery on echocardiography (6% vs 8%; P = 0.78), CT (15% vs 14%; P =0.87), and PET (15% vs 29%; P = 0.09). Additionally, uptake of 18F-NaF was similarly associated with subsequent change in peak aortic velocity (P < 0.001 for each TAVI and surgery).

18F-NaF uptake was the only independent predictor of peak velocity progression on multivariate analysis (P < 0.001).

Serial Analyses Needed

Commenting during the session, co-moderator Stephan Achenbach, MD (University of Erlangen, Germany), said some have worried that balloon expansion “might damage the leaflets and this might be the nidus for microcalcifications” that would spell trouble for these types of devices down the line.

However, Tzolos confirmed no differences between balloon-expandable or self-expanding bioprostheses, and said, “We didn’t have any difference when we did the subanalysis in the uptake between the two groups.”

Session co-moderator Victoria Delgado, MD (Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands), pointed out that due to the study being cross-sectional, “you don’t know if the activity is increasing or not, because you have not really compared the same patient twice in terms of using PET/CT. The only thing that you can say more or less is that the older or the longer the duration was since the implantation, the higher the uptake of the radiotracer. But you don’t know if that is progressing.”

Tzolos said he agreed and that further studies are needed using serial analyses as well as longer follow-up. He also remains “quite confident” about the durability of TAVI valves based on available data.

Should PET Be Offered?

Addressing the proposal raised by Tzolos that PET scans be used after a sufficient interval in TAVI patients to check for disease progression, Grapsa said modality costs would need to be balanced against patient benefits. “Maybe we need to select the populations [for whom] we would do that,” she suggested, adding that younger patients with congenital heart disease might be a good place to start given their longer life expectancy.

“This tool would be for any patient with bioprosthetic or TAVI valve at the moment,” Tzolos added, saying the data don’t indicate a specific advantage with any patient subgroups.

Patients with renal disease also make up a large proportion of TAVI patients and have a high degree of valve degeneration, Grapsa said. This might be a group in whom specialized imaging follow-up might be warranted, although the current study does not provide any clues, since renal disease patients were not singled out in this study. “We have seen even a year after the TAVR prosthesis that the patient might need a valve-in-valve because the valve is going back and being severely narrowed,” she explained.

Nonetheless, one of the most important take homes from the study is its contribution to understanding “the best imaging modality for specific patients,” Grapsa concluded. “For example, for certain populations, maybe a combination of echo and PET would be better than echo and CT. So, this is opening some horizons in understanding the value of different imaging modalities in patients that have a bioprosthesis.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Kwiecinski J, Tzolos E, Cartlidge TRG, et al. Native aortic valve disease progression and bioprosthetic valve degeneration in patients with transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circulation. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the British Heart Foundation.

- kwiecinski, Tzolos, and Grapsa report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments