Prophylactic PCI of Vulnerable Plaques? PROSPECT II/ABSORB

Lipid-rich lesions pose a higher risk, but not everybody is sold yet that stenting these non-flow-limiting lesions is the way to go.

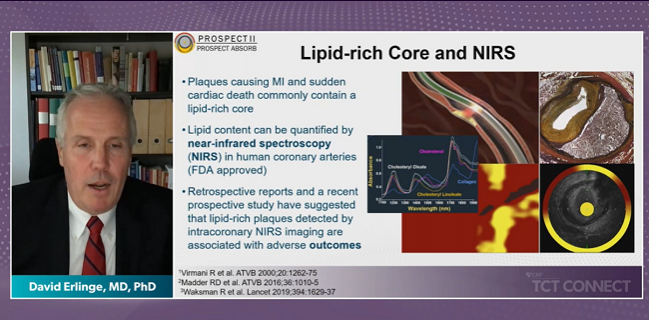

(UPDATED) Patients with vulnerable plaques identified with intravascular ultrasound and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) are at a significantly increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, but prophylactic treatment of those lipid-rich lesions does appear to offer some protection, at least in terms of expanding the lumen area and possibly preventing clinical events.

Those are the conclusions of PROSPECT II and PROSPECT ABSORB, both of which were presented today as late-breaking clinical trials at TCT Connect 2020. The presentations were greeted with a mix of positive and negative reactions speaking to the many uncertainties and controversies in a field that is essentially seeking to identify at-risk plaques and intervene before events occur.

In PROSPECT ABSORB, which was a randomized trial nested within the larger PROSPECT II natural history study, patients with vulnerable plaques treated with a now-discontinued Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS; Abbott Vascular) had a significantly larger minimum lumen area (MLA) after more than 2 years of follow-up than did vulnerable plaques left unstented.

The study is the first randomized comparison of prophylactic revascularization versus guideline-directed medical therapy of angiographically mild/non-flow-limiting lesions with a large plaque burden, according to lead investigator Gregg Stone, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York). The advance of imaging technologies, including IVUS, NIRS, and even optical coherence tomography (OCT), has led to the identification of non-flow-limiting lesions at risk for future events, he said, but whether these lipid-rich plaques with a thin fibrous cap warranted treatment was unknown.

“The question is what to do about them?” said Stone during a press conference. “We wanted to get a sense of whether we could safely treat these plaques and enlarge the lumen.”

Stone said they chose to revascularize with Absorb BVS because published studies have suggested the bioresorbable scaffold would induce neointimal hyperplasia and essentially seal the thin-cap fibroatheroma separating the lipid-rich necrotic core from the lumen. Neointimal hyperplasia would thicken the fibrous cap—turning a thin cap into a thicker cap—and normalize wall stress.

“It should lead to stabilization of the plaque,” said Stone. “Of course, there’s risks in the lipid-rich lesions of embolization and causing periprocedural MIs, and perhaps invoking restenosis, stent thrombosis, and other complications that wouldn’t have happened if you didn’t treat them.”

PROSPECT ABSORB

Within PROSPECT II, which included 898 patients with recent STEMI or troponin-positive NSTEMI successfully treated with PCI, all underwent three-vessel intracoronary imaging with NIRS-IVUS.

Of those, the PROSPECT ABSORB investigators randomized 182 patients who had one or more nonculprit lesions with at least 65% IVUS-derived plaque burden to receive Absorb or medical therapy. That IVUS threshold was chosen because it correlates with a laboratory-assessed plaque burden previously shown to independently predict subsequent lesion-related events in PROSPECT I, according to Stone. All patients in the medical therapy arm were treated with statins, with the majority receiving high-intensity statins, although use of PCSK9 inhibitors was limited.

The primary safety endpoint of target lesion failure—a composite of cardiac death, target-vessel MI, or clinically driven TLR—occurred in 4.3% of Absorb-treated patients and 4.5% of those treated with medical therapy (P = 0.96).

At 25 months, the MLA at the original site was increased from 3.2 to 6.9 mm2 in the Absorb arm but was unchanged in patients treated with medical therapy. The difference in MLA between the Absorb and medical-therapy study arms was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). The MLA across the entire lesion, which includes 5-mm margins distal and proximal to the lesion, was also significantly larger in the Absorb-treated patients at 25 months (5.2 vs 2.9 mm2 with medical therapy; P < 0.0001).

“The BVS-treated lesions had markedly enlarged lesions at follow-up,” said Stone. The lesions treated with medical therapy, on the other hand, were essentially stable.

In terms of clinical effectiveness, lesion-related MACE occurred in 4.3% of Absorb-treated patients and 10.7% in the medical therapy arm (P = 0.12) after a median follow-up of 4.1 years. That reduction was driven by fewer episodes of severe angina. There was one case of thrombosis in the BVS arm, which arose from an occluded side branch without scaffold involvement.

Rishi Puri, MD, PhD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), who wasn’t involved in the study, praised the PROSPECT ABSORB study investigators for the meticulous and difficult-to-perform randomized trial. He pointed out the trial has “something for everybody,” and while the vulnerable plaque hypothesis remains controversial, how physicians view that hypothesis ultimately depends on their biases.

The concept of revascularizing bystander lesions in STEMI patients with multivessel disease—those nonculprit lesions that meet criteria for PCI based on angiography or with physiological testing—is supported by COMPLETE, as well as other studies, although PROSPECT ABSORB takes that concept to a different level given that these so-called vulnerable lesions were non-flow-limiting. Like others, he cautioned against reading anything into the differences in MACE with Absorb and medical therapy, noting it was not powered for clinical outcomes.

“We need to remember this is a systemic disease and that PCI is treating a focal manifestation of that systemic disease,” Puri told TCTMD. “To some, it can seem simplistic to think I’m going to drop in a stent prophylactically at a region that is vulnerable and think that is going to make a huge difference to that patient’s prognosis in the stable or semi-unstable population.” In STEMI, it’s possible that revascularization of vulnerable plaques might be beneficial, but Puri cautioned that placing a stent or scaffold “introduces a new disease, and you want to make sure that the net benefit from introducing a new disease, is better than not stenting and managing the systemic risk.”

Stone said the trial is a pilot study designed to assess the feasibility going forward, but he called the lower MACE rate a “provocative” finding, one deserving of further study in an adequately powered randomized trial.

“I think the results with BVS were really good in this study, but I still don’t think I would use the current-generation BVS [for a future trial],” Stone told TCTMD. “The in-scaffold late loss was still 0.37 mm, which is more than we would expect to see with a metallic drug-eluting stent. Although the lack of permanence of the device is very attractive for a vulnerable plaque application, I would want a more state-of-the-art scaffold. I would be comfortable going ahead with a pivotal randomized trial with a state-of-the-art metallic drug-eluting stent.”

One aspect of care to scrutinize, according to Puri, is how well LDL cholesterol levels were controlled. While most patients received high-intensity statins, it is important to know the baseline and on-treatment LDL cholesterol levels, which weren’t reported in the study. LDL cholesterol should be less than 70 mg/dL, and possibly even lower than 50 mg/dL in these ACS patients.

“One of the most important factors that drives disease progression, lesion stability, or restenosis is your on-treatment LDL cholesterol,” said Puri.

Finally, he noted that patients treated with guideline-directed medical therapy had stable lesions over time, with no change in MLA. “People want to focus on the interventional side because they characterized the lesions as being lipidic, and yes the lumen got bigger [with stenting], but let’s not ignore the fact the medical therapy arm did reasonably well,” said Puri.

Cost-effectiveness of Strategy

Speaking during the press conference, Renu Virmani, MD (CVPath Institute, Gaithersburg, MD), said the higher risk associated with NIRS-IVUS-identified vulnerable plaques is not surprising given previous pathology work. Vulnerable plaques, she said, are essentially precursor lesions and are dangerous even when they are not extremely narrow.

However, she wasn’t completely sold, for now, on the idea that prophylactic treatment of such lesions will reduce future clinical events. Indeed, elsewhere in this same session, discussing COMBINE OCT-FFR, Virmani commented that she would prefer an noninvasive therapy that could stabilize high-risk plaques.

Turning her attention to PROSPECT ABSORB, Virmani noted that the lesion-related MACE benefit was driven by fewer episodes of new-onset angina, which would be difficult to attribute to the intervention.

“If you look at your main reason for the better MACE, it’s to do with progressive angina,” said Virmani. “That’s the only real difference between the two groups. . . . To me, that’s dubious. Were the patients totally blinded? Did they know they had something [done]?”

Arnold Seto, MD (UC Irvine Medical Center/Long Beach VA Medical Center, CA), also was somewhat cautious in his take on these new data, noting the pilot study included only vessels 2.5-4.0 mm in diameter and with lengths of 50 mm or less. The trial was inadequately powered for clinical outcomes and utilized a technology that is known to be associated with more stent thrombosis, he added.

“To a large extent it is not surprising that the MLA remained larger in the poststenting group after 25 months,” Seto told TCTMD. “The absence of a difference in target lesion failure suggests this might not have mattered.” Like Virmani, he pointed out that the lesion-related MACE endpoint could be subject to bias since patients, informed they had a non-flow-limiting but high-risk lesion, might be more likely to present with angina. These critiques are similar to criticisms leveled at the FAME 2 study, he said.

Stone defended the endpoint, saying that new-onset severe angina was adjudicated with angiography, with documented lesion progression in follow-up. “If we randomized enough patients, I do think there’d be some reduction of more clinically severe events, but we weren’t powered for that in this trial,” he said.

For Seto, PROSPECT ABSORB was a “gutsy” trial, but one that opens Pandora’s box for the cardiology community.

“Does this study really merit a larger clinical trial?” he asked. “Probably not with BVS, and I would be concerned about the numbers needed to show a difference.” The ongoing 1,600-patient PREVENT trial may provide more evidence to support the vulnerable plaque hypothesis.

Bigger picture, though, Seto said prophylactic stenting of lipid-rich plaque has significant policy implications because looking for vulnerable lesions with NIRS-IVUS is laborious and expensive, as is prophylactic stenting with its accompanying dual antiplatelet therapy. The clinical benefit of such a strategy would likely be small unless researchers can identify the riskiest of the high-risk lesions. He also harkened back to lessons from the ISCHEMIA trial and all other stable angina trials.

“When the MACE rates for stents versus optimal medical therapy are similar for stable angina patients with truly hemodynamically-significant lesions, can we realistically expect a difference with preventative stenting in non-hemodynamically-significant lesions? It is difficult to imagine that such a strategy could be cost-effective compared with medical therapy. We should focus on patients with symptoms and ischemia, as in the FAME 2 trial,” Seto observed.

Seto added that three-vessel intracoronary imaging is not risk-free, with a 1.6% complication rate. He also noted that when high-risk lesions become a problem, the patient usually presents with angina and not death or MI. In other words, it may be safe to leave these lesions alone until they become clinically relevant.

Ron Waksman, MD (MedStar Heart and Vascular Institute, Washington, DC), on the other hand, was more enthusiastic about the new results, saying PROSPECT ABSORB substantiates the hypothesis that lipid-rich plaques detected by NIRS-IVUS can be treated safely with BVS, and most likely best-in-class DES, as a potential means of reducing future events.

Waksman, who conducted the Lipid Rich Plaque (LRP) study showing NIRS could identify high-risk vulnerable plaque in non-flow-limiting lesions, told TCTMD the new study corroborates the LRP study and predicted these new data “may open a new frontier for interventional cardiologists for the treatment of vulnerable nonstenotic lesions as a secondary prevention.” However, he stressed only a sufficiently powered clinical trial will determine if this strategy should be advocated, noting, like the others, PROSPECT ABSORB was only a safety study.

PROSPECT II

In PROSPECT II, investigators evaluated the natural history of 805 patients who weren’t randomized in PROSPECT ABSORB or who received guideline-directed medical therapy in the study. Again, these patients all had one or more non-flow-limiting lesions with 65% plaque burden and were followed for median of 3.7 years.

The primary endpoint of cardiac death, MI, or unstable angina/progressive angina requiring revascularization and/or confirmed lesion progression occurred in 13.2% of all patients at 4 years. The majority of events occurred in the untreated non-flow-limiting lesions (8.0%) while culprit-lesion MACE occurred in 4.2% of patients, a lower rate than in previous studies.

When investigators stratified the nonculprit lesion-related MACE rates based on the NIRS-derived plaque burden, those in the upper quartile of the maximum 4-mm lipid core burden index (maxLCBI4mm ≥ 325) had a 10.1% risk of MACE compared with 4.8% among those with less plaque burden (OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.18-3.69).

“If you have a highly enriched plaque, then the patient risk [of MACE] was doubled,” said lead investigator David Erlinge, MD, PhD (Lund University, Sweden).

When high-risk plaque was defined as lesions with a plaque burden ≥ 70%, 11.0% of these patients had a nonculprit-lesion-related MACE compared with 3.6% of those with less severe plaque burden. Finally, when investigators combined the two features of high-risk plaques—extensive plaque burden with a large lipid-rich core—these individuals had a significantly increased risk of nonculprit-lesion-related MACE than did all other patients. For example, nonculprit lesion-related MACE occurred in 7.0% of patients with both these features but just 0.2% of patients without either of the high-risk features.

“This imaging technology can both find plaques that are high risk and also find plaques that you can defer from treatment,” said Erlinge.

Adnan Kastrati, MD (Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Munich, Germany), who commented on the findings during the press conference, called PROSPECT II an important study but added it would be nice to identify correlates between the intracoronary measures of high-risk vulnerable plaque with noninvasive imaging, such as CT angiography.

“This [study] is only for patients who come to the cath lab due to a culprit lesion,” said Kastrati. “The problem is that these [vulnerable plaque] characteristics might also be found in patients without a culprit lesion. For me, it’s important to go to the next step to find noninvasive examinations that correlate with these intravascular findings.”

Erlinge is hopeful that CT angiography might one day be used to identify potential high-risk patients with lipid-rich vulnerable plaques who could then be referred for more definitive intravascular imaging. At the moment, if vulnerable plaque is detected on IVUS, NIRS, or OCT, Erlinge said physicians should double down on aggressive lipid lowering while they await clinical studies to determine if revascularizing these lesions lowers the risk of clinical events.

Note: Stone is a faculty member of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Stone GW, Maehara A, Ali ZA, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for vulnerable coronary atherosclerotic plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Stone reports speaker honoraria from Cook; consulting to Valfix, TherOx, Robocath, HeartFlow, Gore, Ablative Solutions, Miracor, Neovasc, Abiomed, Ancora, Vectorious, Cardiomech; and equity/options from Ancora, Qool Therapeutics, Cagent, Applied Therapeutics, Biostar family of funds, SpectraWave, Orchestra Biomed, Aria, Cardiac Success, and Valfix.

- Waksman reports consulting/honoraria/speaking fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardioset, Cardiovascular Systems, Medtronic, Philips Volcano, and Pi-Cardia; and investments in MedAlliance.

- Erlinge, Kastrati, Virmani, and Seto reports no conflicts of interest.

- Puri reports being a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Philips, and Centerline Biomedical.

Comments