Shirlene Obuobi, MD

As a published novelist and accomplished cartoonist, this second-year cardiology fellow seeks to carve out her own path.

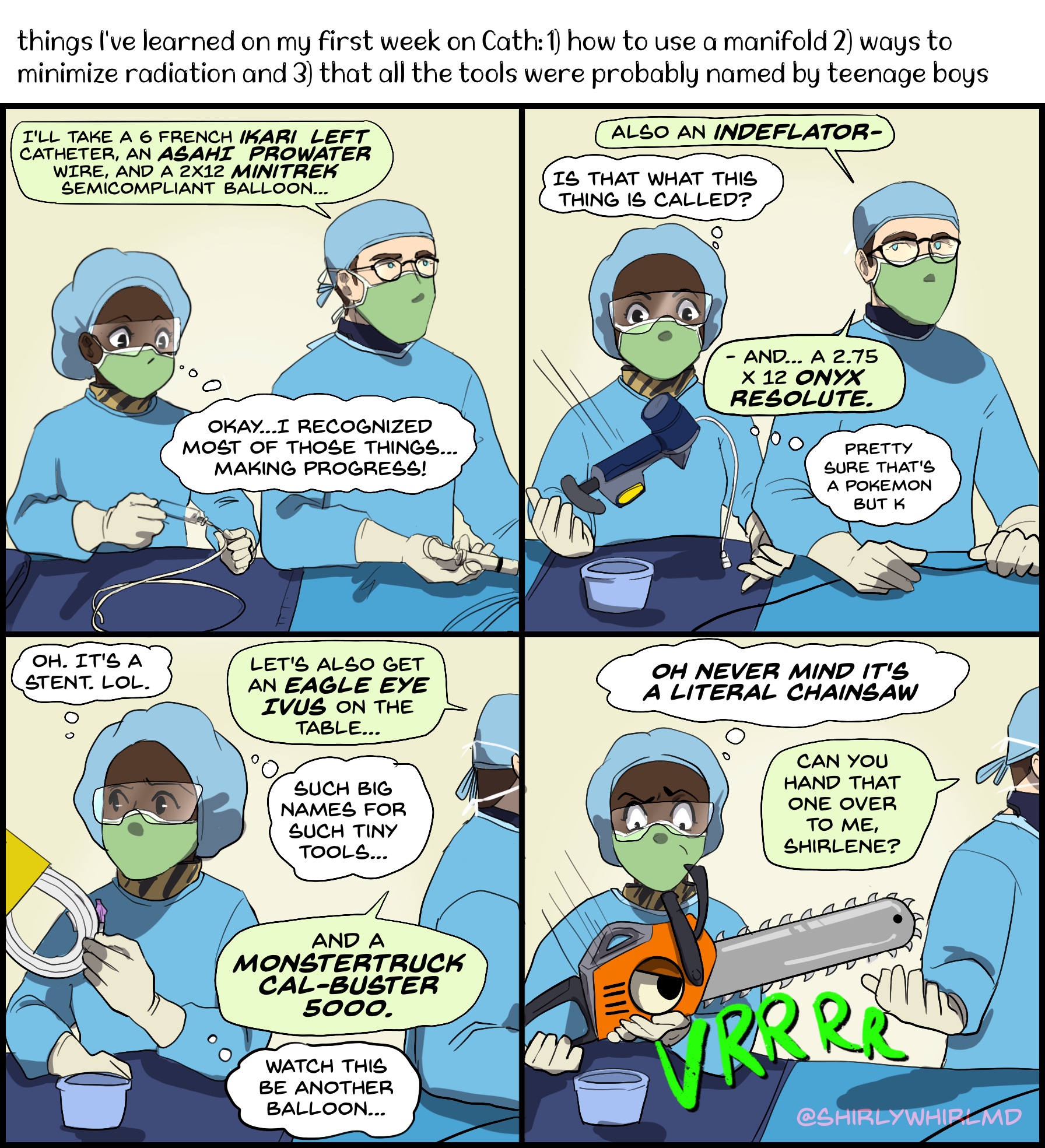

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, is a second-year general cardiology fellow at The University of Chicago Medical Center, where she also completed medical school and internal medicine residency. She is a published author—her debut novel On Rotation was released in July—and cartoonist with a large following on Instagram @shirlywhirlmd where she shares her perspectives on healthcare, medical training, and more. Born in Ghana, Obuobi came with her family to the United States when she was 6 years old and attended Washington University, St. Louis, MO, for undergrad. She has always had a passion for creating and is a self-taught artist and writer. Obuobi was drawn to the field of medicine, and specifically cardiology, because of the connection she could have with patients and their families. Following fellowship, Obuobi hopes to have a hybrid career as both a creator and a physician, and would love to continue working with trainees so as to empower especially those who come from underrepresented demographics.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, is a second-year general cardiology fellow at The University of Chicago Medical Center, where she also completed medical school and internal medicine residency. She is a published author—her debut novel On Rotation was released in July—and cartoonist with a large following on Instagram @shirlywhirlmd where she shares her perspectives on healthcare, medical training, and more. Born in Ghana, Obuobi came with her family to the United States when she was 6 years old and attended Washington University, St. Louis, MO, for undergrad. She has always had a passion for creating and is a self-taught artist and writer. Obuobi was drawn to the field of medicine, and specifically cardiology, because of the connection she could have with patients and their families. Following fellowship, Obuobi hopes to have a hybrid career as both a creator and a physician, and would love to continue working with trainees so as to empower especially those who come from underrepresented demographics.

What initially interested you in a career in cardiology?

My journey to cardiology was a little bit unconventional, because I was quite resistant to it at first. I've always been artistic and creative, and I didn't necessarily see too much of that in the cardiology field. But I fell in love with the physiology. I liked that it was the kind of field in which you didn’t have to rely on rote memorization and could reason through a patient’s pathophysiology. I feel like general cardiology takes the best parts of being a primary care doctor, where you get to see patients at clinic and really become almost like a part of their family, but with more specificity and diversity in what you can do. Cardiovascular disease is still the number one killer in America, and, as someone who’s passionate about healthcare disparities, I also want to use my training and knowledge base to teach patients and laypeople about how to prevent it.

How did you get started with writing and drawing?

I have been writing and drawing since I was a child. I think my very first illustrated novel was when I was 6 years old, and I have something from when I was 10. It's been an intrinsic part of me since I was a kid and something that I've always turned to as an avenue for self-expression. I honestly couldn't tell you how it started. All I know is I read a lot and I liked to copy illustrations, but I've been like this since I was basically able to talk. I'm a self-taught artist. I took an art class at high school and a couple of creative writing courses in college but have had no other formal instruction.

With cardiology training being all-consuming, how did you find time to write a novel?

I have always been asked about finding time! I think, for me, it's less about finding time and more about doing what I needed to for self-expression and to process a lot of what I was seeing and going through. I have a comic platform, called @ShirlyWhirlMD, and I post my comments on Twitter as well. I do a lot of creating on the fly. I draw in the hospital often during rounds, because it helps me focus. I write between patients and on my days off. I kind of make time. That means I'm never caught up on the latest Netflix shows or things like that, but it definitely is something that's good for my own wellness. Creativity is often a two-way street and being able to process my work with and learn from other people has been a great part of this experience.

The beautiful part about my writing is that it's being exposed to people who have nothing to do with medicine—who are completely outside of it—and who now have a way to relate to it and learn about it. There are also the people who are in medicine who feel very well represented by my book, which is very much what I wanted. My dedication talks about how I wrote On Rotation for Black girls in medicine and dark-skin girls and all of us who really put our personal lives on hold and pursue a STEM field or something else that was all-consuming. And so it's been amazing to see people really receive that, but also amazing to see people who have nothing to do with medicine also learn from it.

What does it mean to you to be that person who is exposing the world of medicine to people who aren't in it on a daily basis?

People always ask me why I don't leave medicine and just pursue art full time. What I often tell them is that my training informs my art and vice versa. I don’t know if “callings” exist, but I do feel like I have a particular set of skills that make it easier for me to make difficult subjects digestible and approachable. I think my command of art and medicine will give me the ability to impact a larger number of people that I ever could in an office. I'm using the knowledge that I've gained as a trainee to really help inform others and do it in a way that doesn't necessarily feel like work.

What is it about being a physician, and specifically a cardiologist, that makes you want to continue on with your clinical work?

I’ll admit to having a bit of a savior complex. As I said, I love the physiology in cardiology, but I don’t know if I would have chosen it based on that alone. There are still very few female cardiologists, and even fewer Black female cardiologists. Seeing that there was a clear need to have someone who could relate to but also reflect my own communities, in particular, was also a really, really major driver for me. What brought me to medicine in the first place was the fact that I knew that I'm the kind of person who needs a very clear reason to get up and go to work every day. Without that I'm quite lazy, honestly. Knowing that I need to be there because someone actually has a dire need to see me, a physician, a cardiologist, motivates me. I'm a physician who likes to make close relationships with patients, for better or for worse, and becoming an extension of a family is helpful for me that way. Cardiology felt like the way to get me that expertise that I wanted: a whole lot of skills in imaging and some procedural skills, as well as the ability to have long-lasting relationships with patients. I felt like cardiology gave me that breadth plus some specificity in order to be that expert for patients.

What kind of career in medicine do you foresee yourself having after you finish training? What do you want to be doing every day?

With everything else I do, I know I'm going to have to be part-time to make this work. There's a reason why there aren't that many women cardiology, and some of that, to be honest, is we just don't have the support structures in place to allow people to be too much more than cardiologist and mother, and that's a goal of mine. I also have this writing career and my art career, so while I would love to practice in an academic environment where I would have exposure to trainees, I also need to go where I am most appreciated. What I do is quite nontraditional—juggling art and writing alongside clinical duties is not your typical NIH grant-funded research—but I still will require time for it. I also do quite a number of speaking engagements as is. I think I would anticipate having, say, two half days of clinic a week, a half day here or there to read imaging studies, and a few weeks on inpatient services a year. But I would need my future employer to really see the value in my creative work and allow me the flexibility to continue it.

When you talk to your peers who have certain creative ambitions, what is your advice to them in finding that balance with being a physician and then also pursuing these passions?

My advice might be a little bit not what people expect. I would say that, honestly, it depends on where in their journey they are. If I'm speaking to medical students or residents, I tell them to not expect to be superhuman. I'm not calling myself superhuman per se, but I am saying that for me, creating gives me more relief than it does stress, and that's not always the same for everyone. So I would say that if you are pursuing something competitive like cardiology, you have to focus on the things that the field values first. If you can do that and still add on the creative aspects without compromising your chances to get ahead, then I would of course encourage them to do so.

For those people who maybe are like me, I think it’s necessary to be very intentional about how you use your time and also to set goals early on. I knew I wanted to pursue traditional publishing. I knew that I wanted my work to be seen, and that meant that I researched as I was writing what I would have to do to reach that goal. It meant that I was choosy with how I spent my time and also that I nurtured a really amazing, incredible support network. I could often double up on my creative work and quality time with my husband and friends, because they would help me work through plot points.

What were the biggest challenges that you had to overcome?

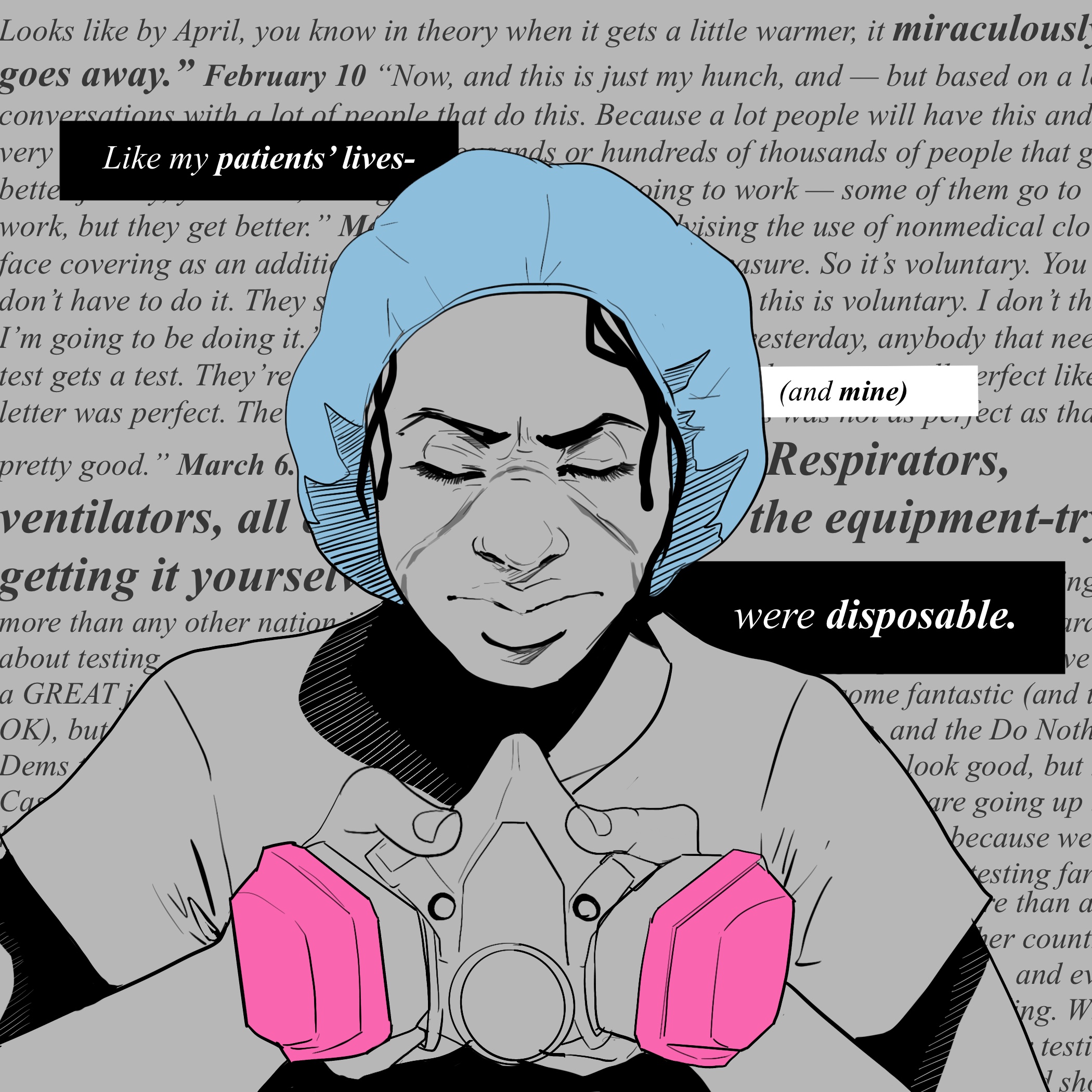

As I mentioned before, in order to make it into cardiology, I had to be mindful of what the field currently values and make up for my deficiencies in those areas. I’m not a great test taker, so I had to bust my behind clinically and remain as well-read as possible so there wouldn’t be concern about my having a deficit in knowledge. I also had to make sure that I had adequate research output, because despite the potential for impact my creative work has, it’s not always been considered relevant to my abilities as a cardiologist. It meant that when everybody else was working our 60–80-hour weeks as a resident—and at times that got more intense because of the pandemic—it meant that I was making sure that I was writing papers and being productive in research while also trying to pursue my other lifelong dreams on the side. I used to feel a need to justify my existence within cardiology. But now, I've been on Good Morning America and shaken hands with Robin Roberts. I’ve made friends with authors who are household names. I’ve gotten messages from young medical students telling me that they felt seen for the first time in my work, and that they now feel empowered to consider cardiology, too! And because of that, I no longer feel the need to validate my presence. I think there may be folks who never pick up what I’m putting down, but I’m at peace with that.

Did you find when you were choosing places to train that you were seeking out mentors who would help you balance out your dual goals?

When I was seeking out places to train, I sought out places that understood my vision. I don't know whether I can go so far to say it's a true road that has not been traveled before, but it's not one that's well traveled. I did need people who saw and believed in what my vision was, which is what I definitely felt about the University of Chicago. They saw who I was, saw what my potential was, and thought that I had potential for great good. And they weren't trying to necessarily conform me to the typical academic mindset, which is: “How do we take a work of fiction and make it into something that is publishable in JAMA?” or “How do we get you into a master’s program so that you can get the ability to do the research?” I didn’t necessarily think that was the right fit for me. I didn’t think I needed those things. They just respected what I could bring to the table at face value.

If you have any, what do you like to do with your free time?

I love playing with my three cats. I spend a lot of time exploring the city for new coffee shops to work in. I took a month of leave to be able to debut my novel and so I've been biking around the city looking for new places to work and eat. I like to travel. I've been to all of Eastern Europe, Costa Rica, and Mexico, and I'm excited to start again hopefully if we get some improvement in our COVID numbers.

Was there anything else you want to make sure people know about you?

It's hard because I don't want to criticize our profession, but I do think that there's so much room to allow for different kinds of people into cardiology. I'm really hoping that by doing what I'm doing and being successful in it, I'm able to open the door a little wider for people who are a little bit out of the box, who still have a place and a lot to offer within cardiology.

*To nominate a stellar cardiology fellow for the Featured Fellow section of TCTMD’s Fellows Forum, click here.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full Bio

Comments