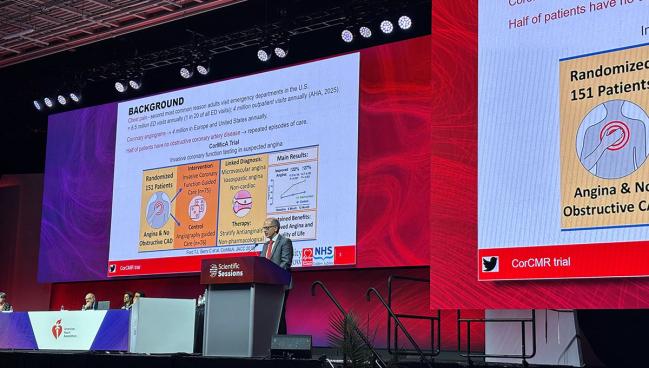

Stress CMR Facilitates Diagnosis, Targeted Care in ANOCA: CorCMR

Quantifying blood flow instead of relying on angiography alone led to a change in diagnosis for 53% of patients.

NEW ORLEANS, LA—For patients with angina but no obstructive coronary arteries (ANOCA), stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) can be used to fine-tune understanding of what’s driving symptoms and improve 1-year outcomes, data from the CorCMR trial suggest.

With the additional perspective provided by CMR on top of angiography, this “endotyping-informed therapy revised the diagnosis in more than half of the participants and improved angina and health-related quality of life,” Conor P. Bradley, MD (University of Glasgow, Scotland), and colleagues report in a paper published simultaneously in Nature Medicine to coincide with the trial’s presentation earlier this week at the American Heart Association (AHA) 2025 Scientific Sessions.

Senior author Colin Berry, MBChB, PhD (University of Glasgow), who shared the data in a late-breaking session, noted that chest pain is the second most common reason for adults to visit US emergency departments—amounting to 6.5 million visits annually.

“This translates into a large number of coronary angiograms being performed. . . . We also know that half of all people undergoing invasive coronary angiography have no obstructive coronary artery disease,” said Berry. “This leaves open the explanation of the cause of the chest pain in these individuals and brings uncertainty leading to repeated episodes of care.”

Previously, the CorMicA trial showed that invasive coronary function testing, as an adjunct to angiography, could change management and improve both symptoms and quality of life in patients with ANOCA.

“Now we ask the question at a different stage in the care pathway: after the coronary angiogram,” Berry said. The question here is whether noninvasive imaging of myocardial blood flow could inform diagnosis and improve health status.

As he noted during an AHA press conference, “It’s all very well to have a diagnosis, but what’s the implication for the individual?” Questionnaires conducted over 12-month follow-up showed that the “changes in medication, better control of blood pressure, preventive therapy, and potentially an increase in physical activity” could enable more precise understanding of the patient’s condition, translating to better health status, Berry explained.

Robert Harrington, MD (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY), commenting on the new results for the media, said CorCMR “is a nicely done study that can affect practice and clearly will change some of the evidence base that we now have in the chest pain guidance.” It’s especially impressive, he added, because “strategy trials like this are notoriously difficult to do.”

Referring to the 2021 US guidelines for chest pain, Harrington pointed out that “when you look through that document, there is a striking lack of high-quality evidence as to what to do with this group of patients.” These individuals are “often ignored,” he continued. “It’s a group of patients that are often told they don’t have anything wrong with their heart. And that’s because the lumen looks okay.”

CorCMR showed that more-thorough testing imparts “better diagnoses, so people were no longer being told that it wasn’t their heart [and had] increased use of evidence-based medications,” Harrington noted.

What CMR Adds

CorCMR investigators enrolled 250 patients (mean age 63.3 years; 50.4% female) with both chest pain and unobstructed coronary arteries within 3 months of their angiogram. Seventeen percent had diabetes, 42% had a history of hospitalization for chest pain, 22.4% had previously undergone coronary angiography, 16.4% prior PCI, and 12.0% had prior MI. Just 5.6% had had coronary function testing. Before enrolling in the trial, 97.6% had been diagnosed by their cardiologist as having noncardiac chest pain.

All underwent adenosine stress perfusion CMR-guided management, which assesses myocardial blood flow, though healthcare teams and patients were blinded to the information that testing added to what was known from angiography. The participants were randomized to an intervention or control group; in the intervention group, CMR results were used to guide diagnosis and treatment, whereas in the control group, treatment was based solely on the angiogram.

Reclassification of the initial angiogram-based diagnosis, one of the study’s primary endpoints, occurred in 53.0% of patients thanks to CMR imaging. Microvascular angina was the most common diagnosis, at 51.0%, followed by noncardiac chest pain (47.0%), “other diagnoses” (1.6%), and vasospastic angina (0.4%). None had obstructive coronary artery disease.

Additionally, mean Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) summary score at 12 months, which served as the study’s other primary endpoint, was 70.9 in the intervention group and 52.1 in the control group, with the higher score indicating less angina, fewer functional limitations, and better quality of life. Score changes from baseline in the two groups were 21.7 and -0.8, respectively, with an adjusted mean difference between them of 20.9.

At 12 months, the researchers also found better results with the intervention versus control for the secondary outcome of EQ-5D-5L score (adjusted mean difference 0.9). Moreover, patients whose care was guided by CMR were significantly more likely to be taking antianginal medicines (84% vs 64%), aspirin (77% vs 56%), and statins (82% vs 62%).

No adverse events occurred in relation to undergoing the stress CMR. Importantly, too, “the results apply equally by sex but are perhaps particularly relevant to women,” who experience chest pain due to microvascular disease more often than do men, said Berry.

He concluded: “In suspected ANOCA, coronary angiography should include a functional test, either invasively or noninvasively.”

Janet Wei, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), the assigned discussant for CorCMR, agreed ANOCA “is not a benign condition,” but rather is one that’s associated with increased event risk and higher cost of care.

Clinical guidelines already endorse testing to tease out endotypes—in the US, both invasive and noninvasive testing have a class 2a recommendation, while in Europe, noninvasive testing with cardiac MRA has a class IIb recommendation, said Wei. “What we know is the test choice should be guided by the local expertise and the availability at their centers.”

Given the previous CorMicA trial’s results, “it’s not surprising that linking the diagnosis of the endotypes—whether [patients] have microvascular angina, vasospastic angina, a combination, or noncardiac chest pain—with the medical therapy does improve angina as well as quality of life at 1 year,” she commented.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Bradley CP, McKinley G, Orchard V, et al. Endotyping-informed therapy for patients with chest pain and no obstructive coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Nat Med. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- This study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and research support from the Scottish government.

- Berry reports consultancy and research agreements for his work with Abbott Vascular, AskBio, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CorFlow, Edwards Lifesciences, MAIA Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Servier, Novartis, Xylocor, and Zoll Medical.

Comments