TAVI, SAVR Almost Equally Performed in California Patients Under 60

The analysis, for 2013-2021, found a higher death risk at 5 years with TAVI, but some urged caution in interpreting that finding.

SAN ANTONIO, TX—Almost half of patients aged 60 years or younger treated for aortic stenosis in California in 2021 received TAVI instead of SAVR, according to new administrative data. More worrisome, TAVI was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of death at 5 years when compared with surgery.

Current US and European guidelines recommend SAVR for patients with severe aortic stenosis under the age of 65 due primarily to limited data in this age group, as those younger than 65 were excluded from the major randomized trials in this space. Beyond this there are concerns about durability, given that younger patients have several decades of life to live.

“The goal of our study is to show that the practice paradigm is changing and to reflect on the fact that we don't have all the answers that we can give to patients,” Jad Malas, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), who presented the data in a plenary session this weekend at the 2024 Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) conference, told TCTMD.

“I think everybody at this conference, and I think even our interventional cardiology colleagues, are interested in knowing whether or not their transcatheter intervention can hold up long term,” he continued. “And patients have the right to know that. We need to fully inform them about the two different options. So, we're hoping that this study sparks renewed interest in performing randomized trials in this space or possibly even linking the STS with the TVT Registry to have a greater national cohort with longer follow-up.”

Discussing the study during the session, Joseph Bavaria, MD (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), was amazed that practice patterns in California diverged so much from the clinical guidelines. “A near 50% TAVR rate in young patients less than 60 is actually truly astonishing. However, having said this, the only result that was worse . . . was the mortality favoring SAVR,” commented Bavaria.

Patrick O'Gara, MD (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA), who commented on the findings for TCTMD, said that the study “certainly raises questions as to the decision-making that went into the choice between a TAVR versus surgical AVR for patients in this younger age group. I think that certainly it begs the question as to whether or not there is indication creep in this age group, but I don't think that these administrative databases have enough granular information for us to be able to answer that question confidently.”

TAVI on the Rise

For the study, Malas and colleagues included 2,306 patients aged 60 or younger who underwent TAVI or bioprosthetic SAVR between 2013 and 2021 from the California State Discharge Administrative Database. There were significant differences between the two groups, with those undergoing TAVI less likely to have an elective procedure, being generally sicker, and less likely to have bicuspid aortic valves.

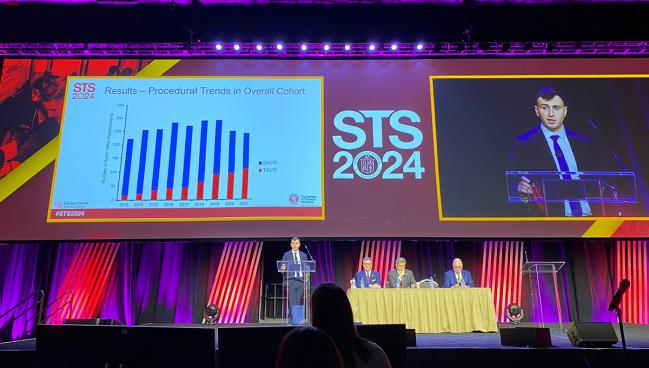

The researchers showed a steady increase in TAVI use for this population over the study period, with an annual increase of about 5%. In 2021, 45.7% of patients received TAVI.

What these patients are lacking when they come to the clinic asking for a TAVR valve at 30 or 40 years is they don't understand that we can perform this operation so safely. Jad Malas

In a propensity score-matched analysis of 358 patient pairs, 5-year survival was significantly greater for those who underwent SAVR compared with TAVI (96.7% vs 88.7%; HR 2.5; 95% CI 1.1-3.7). Notably, though, there were no differences between the groups in terms of 5-year rates of reintervention (5.4% vs 3.3%), stroke (0.7% vs 0.9%), infective endocarditis (0.4% vs 0.6%), and heart failure readmission (2.2% vs 2.2%).

Acknowledging the study’s limitations, Malas said the database lacked information regarding referral patterns, “which may have greatly impacted ultimate procedure choice.” Additionally, they did not have information on transcatheter valve design and echocardiographic follow-up, so they were unable to report on valve durability.

Young ≠ Low Risk

Bavaria noted that the time line of the study poses an additional limitation in that it included patients treated before 2019, when the US Food and Drug Administration approved TAVI for patients at low surgical risk.

“Many of these patients receiving TAVR prior to 2019 had a special circumstance for TAVR indication, possibly not accounted for in a propensity analysis,” he said. He urged Malas and colleagues to “redo a follow-up study in the near future using data from 2019 to 2024 which would give you very large numbers to do a very robust propensity analysis and eliminate FDA approval bias and pre-guideline use.”

“We have to remember as a community that low risk doesn’t always necessarily mean young age and vice versa is also true; young age is not always necessarily low risk,” Malas replied. While the kind of analysis Bavaria suggested might be “fruitful,” he continued, randomized data in this setting or a merging of the STS and TVT databases would be even more powerful.

This is about responsibility. Vinay Badhwar

To TCTMD, Malas added, “our study is obviously not perfect, but we felt like going back to 2013 after [TAVI] had already been approved for high-risk and moderate-risk patients that we were including a diverse enough cohort and a real-world cohort of the same types of patients that come to see us in clinic.”

Regarding why more TAVI patients died than those receiving SAVR even though there were no differences in other secondary outcomes, Malas said they lack the information to really say.

“We need to understand what is happening to these patients 5, 10, 15 years down the line,” he said, adding that future trials should also include valve durability and echocardiographic data. “We need to figure out if these valves are degenerating and they're not getting replaced, either because they don't have a good second option for transcatheter valve-in-valve or because they were deemed too high risk to have a TAVR explant and a surgical replacement.”

Longer-term Data Needed

Everyone seemed to agree that longer follow-up will be imperative, especially for younger patients with who might place more focus on the short term.

Hani Najm, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), a member of the audience, said that his team has been seeing 30-, 40, and 50-year-old patients with aortic stenosis asking for TAVI.

“If I was a patient, obviously the idea of getting a puncture in the groin is much more appealing in the short term than having your chest opened and having open heart surgery,” Malas agreed. “But I think what these patients are lacking when they come to the clinic asking for a TAVR valve at 30 or 40 years is they don't understand that we can perform this operation so safely.”

O’Gara also noted that patient preference has been siding with TAVI over time. “They don't want to interrupt their life schedules; they want to stay in the hospital overnight and go home the next day and not have to stay in the hospital for 5 days and then recover at home from the pain and setbacks that are usually associated in the short-term with heart surgery,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean they should all receive TAVI, O’Gara continued. He urged that clinicians should do “the best she or he can with respect to educating the patient and their family about the lack of mid-term and long-term outcome data in patients who have undergone these procedures in the current era . . . . And frankly, if that is not enough in terms of the negotiations with patients, then I think it would be prudent to ask patients to seek a second opinion about the relative trade-offs between TAVR and SAVR in a younger age group.”

With this study and others like it that have significant limitations, O’Gara cautioned against sensationalizing the findings to suggest differences in short-term outcomes between TAVI and surgery in this young cohort.

Ongoing randomized trials of TAVI versus SAVR in younger patients, as well as those with bicuspid valve anatomy, should give more actionable information for this population, O’Gara added.

“There has to be adequate equipoise across surgical sites in order to conduct a trial of this type, and that's very important to ask on an individual basis because the appetite for randomization for a trial like that in very young patients would vary from one surgical center to the next,” he said.

Failure of the Heart Team?

In a deep-dive session looking at this study, several experts at STS stressed the need for balance when helping a patient decide between TAVI and SAVR. Vinay Badhwar, MD (West Virginia University, Morgantown), said that requires the evidence to be evaluated critically.

“It is troubling that in California and a sample of the nation that TAVR is being done in young patients, but I’m going to step a little higher. This is about responsibility,” he said. When clinicians make decisions that are “not patient focused, that might be related to sales or other issues like that,” this is when trouble occurs, Badhwar added.

S. Chris Malaisrie, MD (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), said that while propensity matching is never perfect, he struggled to think of many patients this age who would benefit from TAVI.

“These are 50-year-old patients. How high risk can they get?” he said.

As the lone cardiologist in attendance at the session, Vikrant Jagadeesan, MD (West Virginia University, Morgantown), was called upon to give his perspective.

“We're all about a balanced approach in the multidisciplinary heart team for . . . the correct intervention for the right patient at the right time,” he said. “It boggled my mind looking at that presentation to see how many young patients got TAVR and personally in my practice, as well as my colleagues’, I would never advocate honestly for TAVR in a patient less than 60 or 65 years old, as a cardiologist, given what I know about the data.”

This is mostly because “whatever you commit to at an early age determines what that patient has down the road, for what we say, the lifetime management of aortic stenosis.”

It's kind of stormy water right now, [and] I think we have to be cautious about what we as surgeons allow to happen knowing this data. Kevin Accola

The dramatic rise in TAVI in this population is “a failure of the heart team and it’s partly our fault,” added Malaisrie. “We have to continue to innovate in what we can offer our patients in the arena of aortic valve replacement. . . . Every company is trying to come up with devices for us to improve our outcomes, make it less invasive, and make it more sellable for our patients. Your cardiologist is going to come to the heart team with the shiniest version 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 valve. It’s incumbent for the surgeon to also come to the table and offer our patients something more than just a full sternotomy.”

Kevin Accola, MD (AdventHealth, Orlando, FL), urged surgeons to spend time with patients explaining these survival endpoints and not just what they can expect from their incision, for example. “It's kind of stormy water right now, [and] I think we have to be cautious about what we as surgeons allow to happen knowing this data.”

“TAVR is an excellent solution for the right person,” Badhwar concluded. “As long as you come to the table with equipoise, with equivalence in being able to make the right decision by tailoring the technology, that’s the success and the definition of a heart team.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Malas J. Guidelines versus practice: a statewide survival analysis of SAVR versus TAVR in patients aged ≤ 60 Years. Presented at: STS 2024. January 28, 2024. San Antonio, TX.

Disclosures

- Malas reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Bavaria reports receiving research grants from Medtronic and Corcym.

Comments