TAVR Yields Similar Success in Failed TAVR or Surgical Valves

But as the patient population shifts younger, strategies for “lifetime management” will be required, experts say.

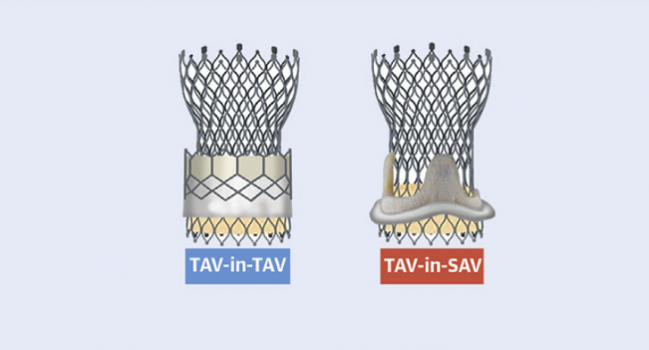

Redo valve replacement using TAVR has similar procedural safety and mortality no matter whether the failed aortic valve being treated is transcatheter (TAV-in-TAV) or surgical (TAV-in-SAV), according to a propensity matched comparison of registry data.

There are trade-offs, however, as researchers report in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology’s first issue of 2021. Specifically, TAV-in-TAV had a higher incidence of mild aortic regurgitation (AR) but lower frequency of residual high valve gradient compared with TAV-in-SAV.

“Surgical aortic valve replacement and transcatheter aortic valve replacement are now both used to treat aortic stenosis in patients in whom life expectancy may exceed valve durability,” write the investigators, led by Uri Landes, MD (St. Paul’s and Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, Canada, and Rabin Medical Center, Tel Aviv University, Israel).”The choice of initial bioprosthesis should therefore consider the relative safety and efficacy of potential subsequent interventions.”

But, as Landes cautioned, these data don’t provide enough specifics yet to guide decisions between one device versus another. “I think it’s premature,” he told TCTMD, adding that what will be more important is knowledge about valve longevity. “If we know we have a good 10 years for a TAVI valve, then we can go ahead and put these valves in younger patients.”

Strikingly, in the current analysis, the repeat interventions were done much earlier when the first procedure had been TAVR—at a median of just 3 years—compared with a median of 9 years after SAVR. The reasons behind this gap aren’t clear, since not all of the redo cases were aimed at fixing degeneration.

Michael J. Reardon, MD (Houston Methodist, TX), commenting on the findings for TCTMD, said they speak to “lifetime management.”

The latest US guidelines for valvular heart disease have eliminated risk from the equation when considering a transcatheter versus surgical strategy, Reardon pointed out. “It just has to do with age, life expectancy, and patient choice.” In surgery, he added, there’s been a move toward bioprosthetic over mechanical valves, which also brings up the issue of durability.

For patients in their 50s or 60s, aortic valve disease may require not only two but potentially even three procedures over decades, Reardon stressed. “What is the way to do this? On one end of the spectrum, if you do it young enough and they need three procedures, you could do surgery-surgery-surgery. Nobody’s going to accept that. At the other end, you could potentially do TAVR-TAVR-TAVR, which has some problems.”

A more likely scenario is a mix of both, he added. “The question is what are the risks? And that’s what we’re trying to work out. And again, if we’re going to do young people, what’s the best way to start out?”

Redo-TAVR Registry

The investigators collected data from the Redo-TAVR international registry, in which 63,876 TAVR patients were treated between April 2005 and April 2019. Among them, 434 of the procedures were TAV-in-TAV and 624 TAV-in-SAV.

Propensity-matched analysis resulted in 165 pairs. Procedural success was higher with TAV-in-TAV than with TAV-in-SAV (just meeting statistical significance), thanks to the fact that residual high valve gradient, ectopic valve deployment, coronary obstruction, and conversion to open heart surgery all trended lower when the failed valves were transcatheter. Procedural safety—defined as freedom from all-cause mortality, stroke, various complications (major bleeding, major vascular, cardiac structural), acute kidney injury, moderate/severe AR, new permanent pacemaker, and surgery/intervention related to the device at 30 days—was similar in the two groups, however.

Need for new pacemaker and moderate or greater AR didn’t differ between TAV-in-TAV and TAV-in-SAV, though mild AR was higher for the transcatheter devices at both 30 days and 1 year. Mortality rates were similar in the two groups.

Redo-TAVR Registry: Propensity-Matched Comparison

|

|

TAV-in-TAV (n = 165) |

TAV-in-SAV (n = 165) |

P Value |

|

Procedural Success |

72.7% |

62.4% |

0.045 |

|

Procedural Safety |

70.3% |

72.1% |

0.715 |

|

Mean Aortic Valve Area, cm2 |

1.55 |

1.37 |

0.040 |

|

Mean Residual Gradient, mm Hg |

12.6 |

14.9 |

0.011 |

|

New Pacemaker |

10.9% |

7.8% |

0.251 |

|

≥ Moderate Residual AR at 30 Days |

8.4% |

4.8% |

0.463 |

|

Mild AR 30 Days 1 Year |

36.1% 36.2% |

17.2% 12.1% |

0.003 0.001 |

|

Mortality 30 Days 1 Year |

3.0% 11.9% |

4.4% 10.2% |

0.570 0.633 |

Regarding the hemodynamic findings, Landes said that when treating a failed TAVR, “you don’t have the surgical suturing, which is kind of restrictive and noncompliant, so you have more potential orifice area. So you can end up with better gradients compared to what you can achieve with TAV-in-SAV. But on the other hand, this surgical suturing might help to achieve better sealing between the two valves.”

Then comes the need for device longevity in younger patients.

Do the striking differences in time to reintervention seen here “imply that TAVR valves are less durable than surgical valves? Likely not,” write Anthony A. Bavry, MD, and Dharam J. Kumbhani, MD (both from UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX), in an accompanying editorial. “Beyond the obvious limitations of an observational study, only 0.7% of all TAVRs in this study required TAV-in-TAV. Even among these, the investigators included patients as soon as 2 days after their initial TAVR implantation; therefore, this study can more accurately be said to examine freedom from reintervention, rather than structural valve degeneration per se.”

Landes agreed. “If a patient did the second procedure 1 or 2 months after the first one, then we should highly suspect that there was something wrong with the implantation—it’s not the valve’s fault but rather the procedure’s fault,” he explained. “But if we’re talking about 2 or 3 years, then it’s hard to say. It’s too soon for a valve to deteriorate on one hand, but it’s too long to wait for patients with suboptimal procedural outcomes.”

Reardon, too, drew attention to the mixed indications for redo valve. “They’re different patient groups, so it’s going to be hard to really match these,” he said. For instance, “why did the people in the TAVR group have TAVR not surgery in the first place?”

Devices, Techniques, and Medical Therapy

For Vinayak Bapat, MD (Minneapolis Heart Institute, MN), the short time frame for TAV-in-TAV is a hint that for some patients TAVR may just not be a good solution. When reinterventions are needed so early, he suggested, it might make sense to go ahead and explant the TAVR device then proceed with surgery—ie, SAV-in-TAV. “We are doing TAVRs now in low-risk and intermediate-risk patients who can still luckily have surgery with equivalent risk,” Bapat said.

TAVR is preferred as a first-line therapy, assuming there’s suitable anatomy, he added. “But when the TAVR fails within 5 years’ time, obviously it’s not working well for that given patient. And if the life expectancy of the patient is going to be reasonable, it’s not fair to subject the patient to another TAVR now, because we are just doing ineffective treatment which is more expensive, of course, and we are pushing the reoperation [back] a few years when patients will be older and maybe sicker.”

Landes, in response, said “it’s a very interesting thought.”

He drew parallels to PCI, where if a stent fails, operators sometimes choose to replace it with one that elutes a different drug, “because the patient might not react optimally to that stent type.” That said, there can be “very bad outcomes of TAVR extraction,” he said. “It’s a very complex surgery and given the excellent results TAV-in-TAV can achieve, it’s going to be a very difficult argument that it’s worth it. But it’s certainly something we need to study, and I hope to have some answers soon enough.”

Another area for growth is better knowledge about how to optimally perform TAV-in-TAV, such as the best implantation depth.

“It’s not like TAV-in-SAV, where the surgical valve is very short and you have the suturing, which guides you and gives you a ‘landing zone,’” Landes noted. “In the transcatheter valves—especially the self-expanding ones, which are very tall and where the leaflets are supra-annular—I think it’s not rare that operators implant the valve below the degenerated leaflets, which in a way can cause what we call leaflet overhang. It might be one explanation for the mild regurgitation and might also affect the longevity of the new [valve] inside the old one.”

There’s also the question of whether a self-expanding valve, if it fails, should then be treated with another one of the same type or with a balloon-expandable valve. The same decision exists “vice versa,” Landes said. “There are four combinations.”

Bapat observed that, beyond the devices themselves, there are also implications for medical therapy across patients’ lifetimes. This study doesn’t provide details on anticoagulant use, he noted. “It’s important for us because TAVR-in-TAVR, there’s a lot of metal now in that small space [and a need for anticoagulation],” whereas TAVR-in-SAVR doesn’t require it except in “small valve combinations.”

All of these decisions underline the importance of a multidisciplinary heart team, he stressed.

Photo Credit: J Am Coll Cardiol. Central Illustration (adapted).

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Landes U, Sathananthan J, Witberg G, et al. Transcatheter replacement of transcatheter versus surgically implanted aortic valve bioprostheses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1-14.

Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ. As patients live longer, are we on the cusp of a new valve epidemic? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:15-17.

Disclosures

- Landes, Bavry, Kumbhani, and Reardon report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Bapat reports receiving grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude.

Comments